America is craving for lower interest rates. While the Federal Reserve is purposefully elusive on its rate cut plans, commentators all over the news media are trying to make those rate cuts happen. Over at CNBC, on February 27th, finance reporter Kelsey Neubauer and her co-writer Dan Avery opined that the Fed’s policy-setting Federal Open Market Committee, FOMC,

will have seven more opportunities to cut interest rates this year, starting with its meeting on March 19 and 20.

In other words, they expect cuts to happen—soon, and often.

On March 1st, economist Preston Caldwell at Morningstar explained:

[We] expect the first federal-funds rate cut to come in May or June 2024, bringing the rate down to 4.00% to 4.25% at the end of 2024. We expect the Fed to continue cutting through the end of 2025, ultimately bringing the federal-funds rate down by over 300 basis points.

Caldwell then shifts foot and starts predicting rates on U.S. Treasury securities, which is a far more dicey endeavor than predicting the Federal Reserve’s rate cuts.

As of March 13th, Phil Rosen with Business Insider was also dreaming of Fed rate cuts:

Markets are pricing in 64% odds of a rate cut in June … even as [Fed Chair] Jerome Powell and his colleagues remain cautious on inflation, jobs, and the economy. Those expectations were little changed after Tuesday’s inflation report, which showed CPI came in hotter than expected in February.

Last but not least, from Reuters, March 11th:

The U.S. Federal Reserve will cut its key interest rate in June, according to a stronger majority of economists in the latest Reuters poll, as the central bank waits for more data to confirm whether inflation is headed convincingly toward its 2% target.

Unfortunately, it is not expectations that determine whether or not a change in inflation is “hot”. That is determined by the facts on the ground in the economy. However, it is an unfortunate, yet widespread habit among reporters, analysts, and other pundits to rely on expectations when they determine whether or not something is changing for the worse or the better.

Since I prefer to analyze the economy itself, not what others expect about it, I am more pessimistic about rate cuts. I was more optimistic at the start of the year because I thought Congress would do something to rein in its budget deficit. But the weeks go by, with remarkable legislative inactivity on this issue; when the members of Congress invite outside advice, it is in the form of the Cato Institute’s Romina Bocchia, who offers them an opportunity to kick the deficit can even further down the road by appointing a fiscal review commission.

This idea, which is gaining traction in Congress, will result in a commission that does nothing about the structural imbalances in the federal budget. This is exactly why it is so attractive: it gives Congress a chance to produce lots of activity but no controversial results. It will be their most substantive response, and a feeble attempt at calming an increasingly nervous debt market.

The Federal Reserve does not listen to the Cato Institute. It listens to the debt market, but the public debate on the issue also matters to them. Given how opinion-makers are working tirelessly to put pressure on the Fed to cut its funds rate, barring an open fiscal crisis, a couple of small rate cuts are inevitable, probably in May and June. However, the end result for the year will be nowhere near what the bolder expectations have predicted.

At the same time, let me repeat that if debt market investors determine that Congress is doing too little, they will at some point force the Fed to raise, not cut, its federal funds rate.

Beyond the debate over expectations, there is also the issue of whether or not interest rates should be cut for the sake of cuts. In other words, even if the Fed determined it appropriate to cut its federal funds rate, there is nothing that says they should cut it.

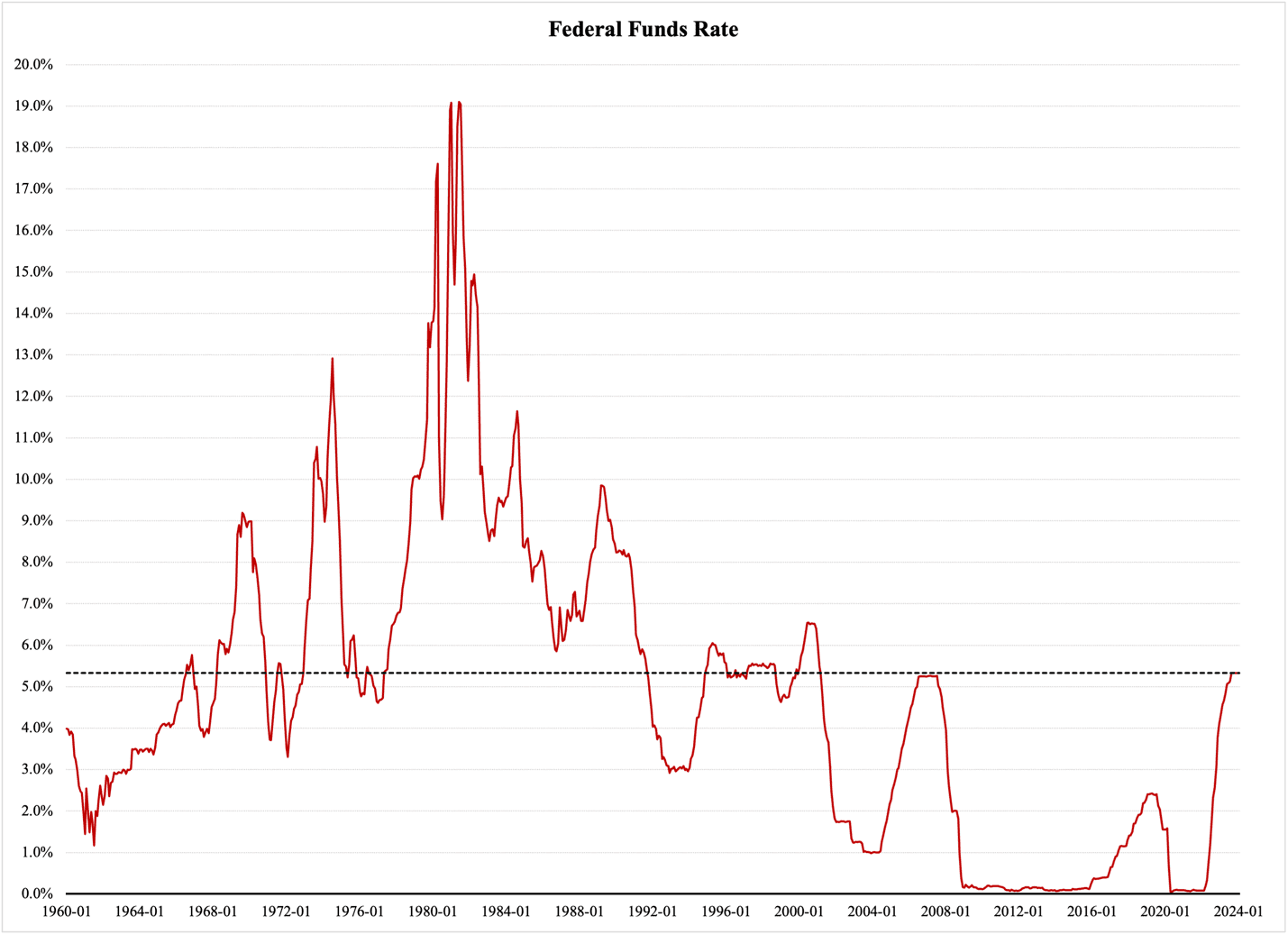

Bluntly speaking, too many people seem to believe that lower interest rates are natural. They are not. Figure 1 reports the federal funds rate since 1960. The dark dashed line compares today’s level of 5.33% to historic levels:

Figure 1

Since just after the 9/11 terrorist attacks in 2001, we have gotten used to an aggressive low-rate policy by the Fed. The last time the federal funds rate was above 5% was in late 2006 and 2007; on average, in the 2000s, the funds rate was 2.96%. In the 2010s it averaged 0.61%.

Compare this to the 5.2% average for the 1990s, which was the first decade since the 1950s with low inflation. Even as inflation receded in the early 1980s, the Fed kept its funds rate high: from 1985 through 1989, the rate was 7.7% on average and never fell below 5.8%.

The 1990s is a good example of how tight monetary policy can be combined with strong economic growth and low unemployment. The Fed could concentrate its monetary policy on keeping inflation down—a point that eludes those who advocate lower rates now. By definition, a lower federal funds rate means a more rapid expansion of the U.S. money supply, and there is no better way to cause inflation than to rapidly expand the money supply.

Rather than thinking about today’s interest rates as abnormally high, we need to think of the past 22 years—and the period from 2009 through 2021 in particular—as an anomaly in monetary policy. A return to interest rates of the 1990s, which again averaged 5.2% for the whole decade, would be highly beneficial:

The last point is very important. If the average interest rate on today’s federal debt were 5%, Congress would have to spend over $1.7 trillion per year just to cover the interest rate bill, compared to just over $1 trillion today. And that is for the debt as it stands today.

Back in the 1990s, America was able to have a thriving economy, strong growth, expanding job opportunities for all ages, balanced government budgets, and price stability—all in one package. All these achievements were built around a sustained high interest rate policy by a Federal Reserve with Alan Greenspan at the helm.