Something is happening to the market for U.S. government debt—and it is not good.

The sign of trouble is in the yield curve, i.e., the statistical image of what yields, or interest rates, a government pays on the various debt securities it sells to the general public. The United States Treasury sells bills, notes, and bonds—Treasury securities—with 13 different maturities, ranging from one month to 30 years. Usually, these securities come with low yields on the shorter maturities and higher yields the longer the life is of the security.

When yields rise with the life of the debt security, we have a normal yield curve. Since the buyer of a Treasury security lends his money to the U.S. government, he should get a higher compensation the longer the period of time over which he pledges to lend the money. However, this is not the case in America today. Since late 2022, the U.S. yield curve has been inverted, i.e., the yields on notes (which last 2-10 years) and bonds (20 and 30 years) have been lower than yields on bills.

The inverted yield curve is bad enough, but the curve is now shifting in a way that shows rising investor dissatisfaction.

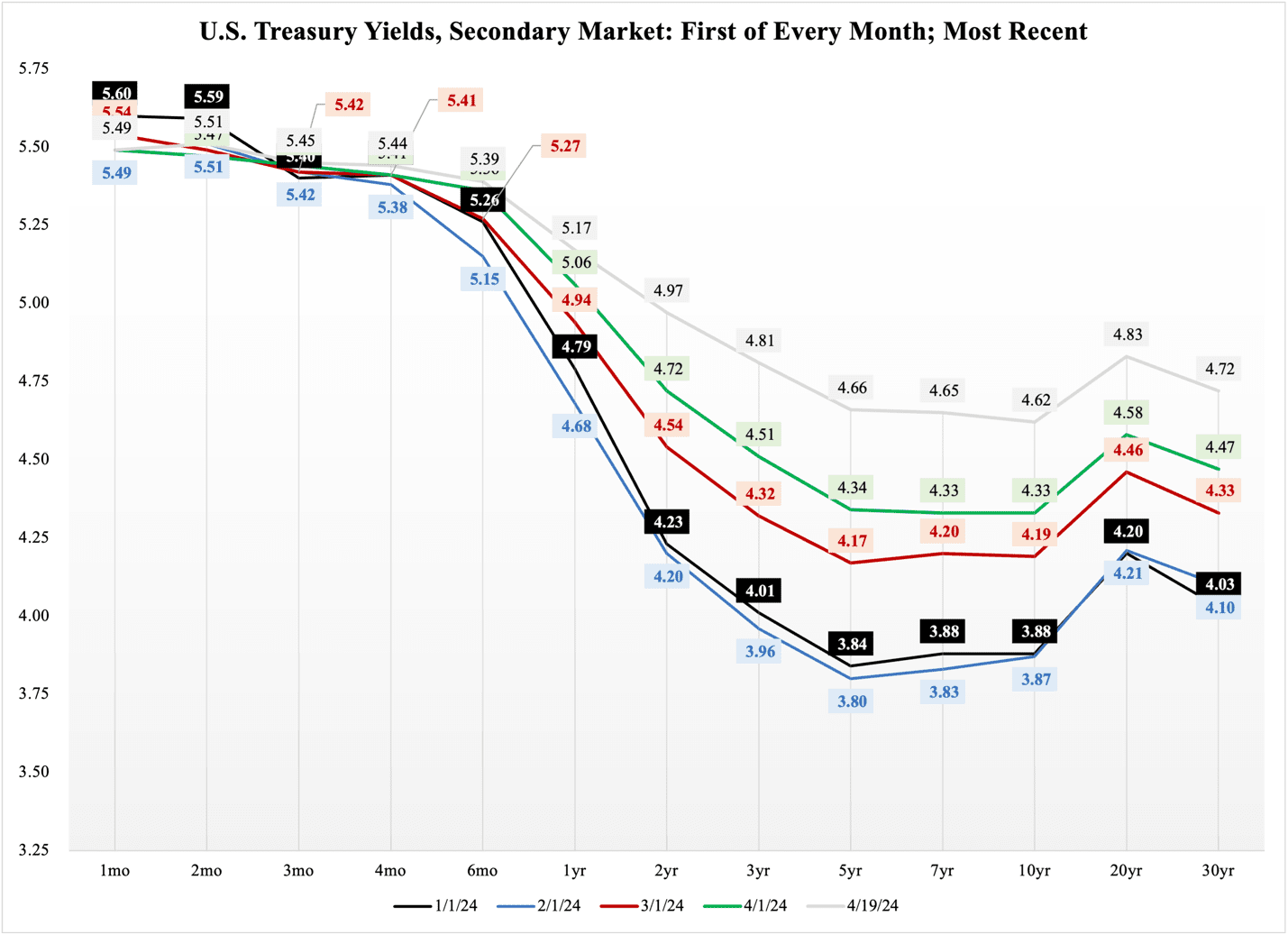

On the upside, if the trend that started this year continues, it could mean the end of the inverted yield curve. This trend would be benevolent if it raised yields on long-term maturities while lowering them in the short end. But these are not normal times: while long-term yields are rising, short-term yields are not budging. Figure 1 reports the yields on the first of every month so far this year, as well as the yields as they were on April 19th:

Figure 1

The 10-year Treasury note is often used as a ‘benchmark’ to gauge where the market is going. Since February 1st, it has risen from paying 3.87% per year to 4.62%. The 5-year note paid 3.8% on February 1st; now it yields 4.66%.

Overall, the notes and bonds (2 years and up) which paid at most 4.21% on February 1st, now pay 4.62-4.97%. This is a strong increase, and it has sustained for so long that it defies temporary swings in the market. Meanwhile, with the exception of some movements in the 1-year bill, short-term yields have barely changed at all.

Some analysts like to link yields on Treasury securities to the Federal Reserve’s policy-setting federal funds rate, but no such link exists here. While Treasury yields are drifting upward, the funds rate has remained unchanged. If there were any expectations in the market of changes to the funds rate, they would have predicted a lowering of that rate.

There are three possible reasons for this odd shift in the yield curve. The first is a widespread disappointment with the fact that the Federal Reserve has not lowered its funds rate yet. Late last year, and even as recently as in January this year, analysts and commentators predicted a cut in the funds rate within a few months. We are there now, and no cut has happened; investors who speculated on a rate cut are now selling their Treasury securities, even if it means taking a loss.

Without detailed proprietary data, it is impossible to independently verify that this is what we are seeing in Figure 1. However, judging from the auctions—the primary market where the Treasury sells new debt—the interest in owning longer-term Treasury debt does not seem to be in decline. There could be a different trend in the secondary market, but it would make no sense for investors to exhibit one type of behavior in the primary market and another type in the secondary market.

The second possible reason for the rising long-term yields is that investors are still worried about inflation. With the consumer price index showing inflation rates in the 3.1-3.5% range for the past six months, it looks like the Federal Reserve is having problems bringing inflation down to the 2% long-term rate that the Fed is targeting.

Expectations of a more persistent inflation rate could definitely explain some of the rising long-term rates, but we should also keep in mind that investors in U.S. Treasury securities have not been accustomed to high real yields in recent years. In fact, we have to go back about a decade to find Treasury yields that paid any substantive margins over inflation. While the yields on notes and bonds back in February were not too much higher than inflation, the current trend is creating real yields above recent averages for the U.S. debt market.

Investors would pursue substantially higher real yields if they were really worried about inflation. Even though the consumer price index (CPI) inflation rate remains well over one percentage point above the Fed’s target, there is no drama to the U.S. inflation numbers. The rate is relatively stable, and its elevated nature is perfectly explainable from an economic viewpoint; furthermore, the Federal Reserve has shown no rush in lowering its funds rate, which demonstrates the central bank’s commitment to fighting inflation.

All this makes it hard to believe that investors demand higher long-term yields out of inflation worries. A more plausible explanation—the third reason for the odd shift in the yield curve—is that investors are seriously worried about the fiscal stability of the U.S. government. This would mean that the rise in longer-term yields is really a rise in the risk premium for owning U.S. government debt.

This risk premium explanation of the elevated flattening of the yield curve is the most likely one. During the period of rising long-term yields, Congress has made only a tolerable minimum of efforts to address its own budget deficit. There is no fiscal leadership in Congress, where, most recently, the focus has been on spending yet more on aid to Ukraine and Israel—obviously without even passing interest in how to pay for that aid.

If the yield curve keeps changing as it has recently, we will reach a point where it starts sloping upward. If we do so without any reduction in short-term yields, it will be the first open vote of no confidence in the U.S. Treasury from the sovereign debt market.

If that does not wake up the fiscally concerned in Congress, nothing will.