Inflation is less and less of a problem in America. Not so in Europe, where the monetarily driven inflation from the past year and a half may be giving way to classic cost-push inflation. The evidence is too scant at this point to draw any definitive conclusions, but the indications are beginning to emerge: we may be witnessing a small but problematic influence of taxes on inflation in the European Union.

If this is the case, it will take new forms of economic policy to beat back inflation; tighter monetary policy does not work against tax-driven inflation. The European Central Bank, which is responsible for fighting current monetary inflation, is aware that inflation may not give in as easily as it has in, e.g., the American economy. In its most recent Economic Bulletin (Issue 3, 2023), the ECB explains that the outlook on inflation “continues to be too high for too long.”

This statement was made just after the May 4th meeting when the ECB’s Governing Council approved another interest rate increase for the euro zone. At the time of the rate hike, the Governing Council expressed an intention to tighten monetary policy—raise interest rates—”sufficiently” to bring inflation down to 2%.

However, the Council also admitted that it may not be able to control inflation going forward in the same direct way that it has so far. This hints at the ECB being aware that inflation may be shifting nature: the Council points to the labor market as a source of inflation:

Wage pressures have strengthened further as employees, in a context of a robust labour market, recoup some of the purchasing power they have lost as a result of high inflation.

As a result of the increased wage pressure, the ECB explains, “some indicators have edged up” their inflation outlook, reducing the likelihood of a timely return to the 2% rate.

This is an error in judgment. In order for wages to drive inflation, the European labor market would have to be drum tight. It is not: per Eurostat, unemployment has remained largely unchanged over the past six months. The rate in March for the entire European Union was 6.0%, minimally lower than the 6.1% in September last year. The number for the euro zone was 6.5% in March, down marginally from 6.7% six months earlier.

National rates vary drastically, from Germany at 2.8% to France at 6.9% and Italy at 7.8%. Spain, the fourth largest euro-zone economy, stood at 12.8%.

With such very different balances between labor supply and labor demand, it is simply not logical that Europe would be facing wage-driven inflation. This may be happening in individual member states, e.g., in Germany, or in Czechia where the unemployment rate for the past six months has fluctuated between 2.2% and 2.7%. However, any economy with unemployment rates at 6% or higher is a far cry from a wage-price spiral.

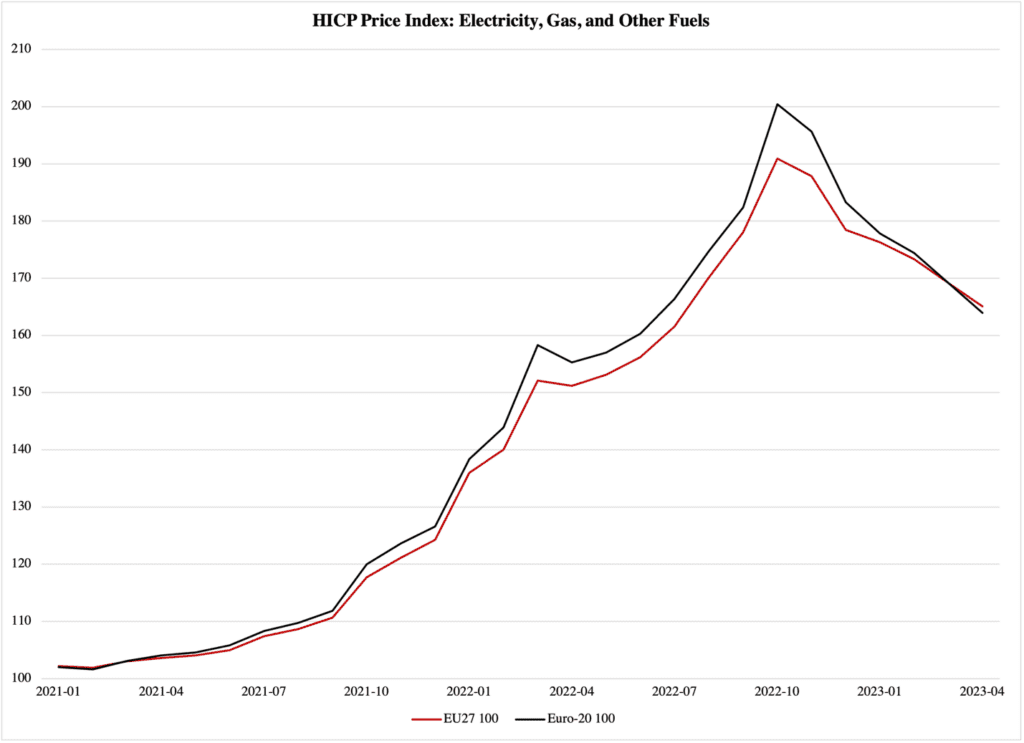

If wages cannot explain why there is a new inflation threat, can energy prices do that? The answer is negative here as well. Figure 1 reports an index over consumer prices for electricity, gas, and other fuels: If consumers paid €100 for a given amount of fuel in January 2021, they paid €190-200 for that amount in October last year.

So far, inflation. But only so far:

Figure 1

Source of raw data: Eurostat

In other words, there is now ‘deflation pressure’ from energy prices, and we can safely assume that it goes beyond the household sector. If prices on fuel for industry input were still rising while household prices were falling, supply would flow from the former to the latter. That would even out the differences until the inflation or deflation rates were similar.

But if neither wages nor energy prices can explain why the ECB is right in being concerned about persistent inflation, then what can explain it?

There is a candidate that nobody wants to talk about: taxes. Figure 2 shows how much taxes have added to EU-level inflation since 2004. After having recently exercised positive influence—in the sense of mitigating inflation—in April this year, taxes once again pushed the inflation rate upward:

Figure 2

Source of raw data: Eurostat

The actual inflation rate for the EU was 8.11% in April. Had taxes been constant, it would have been 7.97%. A tax mark-up of 0.14% may seem insignificant, but it makes a difference over time. From 2004 through 2006, taxes raised inflation in the EU by 0.18% on average. At the end of 2006, consumer prices were 6.5% higher in the EU than they would have been if taxes had not added to inflation.

It is too early to tell if taxes will be a driving force behind European inflation in the coming months. However, the fact that taxes have swung around from dampening to amplifying inflation (‘red’ to ‘green’ in Figure 2), is cause for concern.

Generally speaking, we must not underestimate how tax policy interacts with inflation. The effect from taxes on higher prices is most apparent when it comes to consumption-based taxes. Economists like to refer to these taxes as indirect, as opposed to direct taxes. The distinction is based on how the taxes are collected: direct taxes are paid directly to the government that levies them, while indirect taxes are collected by an intermediary.

Indirect taxes consist almost exclusively of consumption taxes, which are collected by the seller of the consumer good or service. Best known among these is the value-added tax, VAT.

The excise tax is another form of indirect tax.

All indirect taxes raise the price of goods and services, but they do not always exacerbate inflation:

To see the difference between these two relations between taxes and inflation, let us assume that I sell bicycles. I charge €80 apiece. Government adds a 10% VAT, which (ignoring technical complexities with the VAT) increases the price to €88.

Government also imposes two excise taxes: €6 in road-use tax and a €6 environmental impact tax. (On bicycles? Because government can.) The total price is now €100, of which taxes are 20%.

Suppose I have to raise the price because the parts I buy have become more expensive. I now charge €90. The VAT rate is constant, but the higher product price raises the cost of the VAT to €9. The bicycle price is now €99, but we are not done. We have to add the excise taxes.

Before we do that, let us note that so far, the tax burden has not changed. It will, though, if the excise taxes are constant in euros, i.e., if they remain 6+6=€12. The total price will end up being €111, of which the tax burden is 18.9%.

In other words, the tax burden has fallen. Ironically, if I cut the bicycle price back to its original level, the tax burden goes back up to 20% of the total sales price.

Figure 2 illustrates how complex the relationship is between taxes and inflation. Now that inflation is coming down again, the tax-and-price mechanics we just looked at could explain why taxes once again contribute to inflation (the green column right at the end of the timeline in Figure 2).

Taxes can interact with inflation in another way. Suppose that I come into my bicycle store one day and get a notice from the government that their excise taxes have gone up from €6 to €8. I am now supposed to collect €16 in total for the road-use and environmental impact taxes. I pass these taxes on to my buyers by raising the price of each bicycle from €100 to €104. This 4% inflation is caused entirely by taxes, which now account for 23.1% of the total sales price.

In this latest example, inflation is driven by taxes. There is a way that taxes can have even more of an impact on inflation. Let us say that when I open the message from the government saying that they raised the excise taxes, they also let me know that they are now going to calculate the VAT in a different way. Up until now, they have calculated the VAT based on the pre-tax price that I charge for the bicycle, but from now on they will include the excise taxes in that calculation.

Here is how this works. I still charge €80 for a bicycle. The original base for the VAT required me to add €8 to the price, plus €16 in excise taxes. However, since government now wants to include those taxes in the VAT base, the 10% tax rate now applies to €96, not €80 as before.

This tax-on-tax model is absurd from an American viewpoint, but it is not at all alien to tax-crafty Europeans. As for my bicycle, I now have to charge €9.60 in VAT on top of €16 in excise taxes and my own €80. The total sales price is now €105.60. In other words, by raising the excise taxes and broadening the VAT base, government has increased the tax burden on my bicycles from 20% at the original base-and-rate calculations, to just over 24.2%. The inflation in the sales price is 5.6%.

As these examples show, it is easy to create inflation with taxes. It is also easy for government to create a tax system that has a dampening effect on inflation and rewards the economy for price stability. The problem is that tax systems are practically never designed with this intention in mind; legislators are very often satisfied so long as they can just collect the revenue they believe they need (and then some).

Taxes that are not based on consumer spending are by their very nature less inflationary. That does not mean that inflation is immune to them: if government raises taxes on property or on corporate income, then businesses will pass on that increased cost to their buyers. The effect in terms of inflation is less clear than in the case of excise taxes: the role of property costs in business operations—including property taxes—varies substantially from one industry to another, and even between two businesses selling the same product.

Income taxes also have a complicated relationship to inflation. On the one hand, it is reasonable to expect that increases in income taxes motivate workers to demand higher wages and salaries in compensation. This is one form of wage-driven inflation that has preoccupied far too many economists over the years. However, the exact impact of an increase in the income tax depends on how the tax system is constructed: all other things equal, a flat income tax, i.e., one where the same rate applies to all of a person’s income, has the most direct effect on wages. By contrast, if the income tax consists of multiple brackets with different rates for different levels of income, an increase in the tax burden will almost certainly have a disproportionately high impact on high incomes.

Since high-income earners tend to save more of their income than those who make less, it is difficult to assess the precise impact of the tax hike on the economic behavior of those targeted by the tax.

All in all, the impact of taxes on inflation is for the most part a simple and transparent matter. In a coming article we are going to take a look at the structure of the tax systems in the 27 EU member states. Sign up for updates from the European Conservative on Twitter or Facebook, and be the first to know when that article is published!