In an extraordinary announcement on Friday, October 17, S&P Global gave France another credit downgrade. Reports LeMonde:

More than the deterioration of France’s public finances, ratings agency S&P (formerly Standard and Poor’s) penalized the country’s political chaos, on Friday, October 17, when the agency announced it was lowering France’s rating from AA− to A+.

The good French newspaper is making this more complicated than it has to be. The political chaos is a major reason why the French government cannot stop its own fiscal bleeding. If the French public sector’s finances were in good order, Standard & Poor’s would have kept to their normal credit assessment schedule. They would most certainly not have issued this kind of extracurricular credit downgrade.

If there is one message in the S&P’s action, it is that they have had enough of French political deadlock. As much as these credit rating agencies try to be fair to the governments they evaluate, there comes a point where that fairness no longer works to the advantage of the evaluated country.

That is where France is now—and the French political elite darn well better wake up and smell the coffee.

As someone who has analyzed and written about European public finances for the past 20 years, I am surprised that it has taken S&P and the other rating agencies this long to issue an ‘enough already’ note. Now that it is finally here, it is essential to understand the gravity of it, and the background that brought France to this point.

France has one of the most notorious deficit-spending governments in Europe. As Figure 1a below explains, in 2024, the consolidated budget deficit for the entire French public sector was 10.2% of total spending. This number includes all levels of government, from national down to municipal. However, practically all of the deficit is in the budget that the National Assembly is responsible for.

However, as frightening as that number is, it is only the last in an endless streak of deficits:

Figure 1a

There is a point in measuring budget deficits as a share of total spending. It shows exactly how many euros the government has decided to spend in excess of what its revenue can pay for. Although S&P uses the milder, less blunt deficit-to-GDP ratio, the trend is pretty much the same.

This decades-long flow of red ink through the government coffers is now beginning to show up in the cost of government debt. If anything should send up a big, red flag in Paris, that cost hike is it.

Before we get there, though, let me make one more point about why we can expect the international credit rating agencies to basically give up on France. The four arrows in Figure 1b below represent four different fiscal trends in France’s recent economic history:

Figure 1b

During the first trend, from 1995 just across the step into the new millennium, the French government actually managed to reduce its excess spending. When the Millennium Recession hit in 2001, French taxpayers covered €97.50 of every €100 that their government spent.

After the recession, France joined most of the euro zone members at the time in shifting their attitude to the EU’s fiscal rules. That thing with balancing the budget and keeping debt down was no longer as important as it had been during the 1990s run-up to the euro zone’s creation.

Due to this more relaxed attitude to fiscal responsibility, France went into the Great Recession—the beginning of the third trend—borrowing €5.60 of every €100 in government spending. After a couple of agonizing years with 12+ percent deficits (again as a share of spending), the French government was able to put its fiscal house on an encouraging track toward smaller deficits.

Unfortunately, this improvement in public finances was the result of a long, slow but persistent upward trend in taxes. In 2007, the year before the Great Recession, total taxes claimed 50.4% of the French GDP; a decade later they had increased to 54.3%.

The higher taxes have left an indelible mark on the French economy. They made it markedly more difficult for the country to come back after the 2020 pandemic and its forced economic shutdown. As a result, the fourth trend in Figure 1b is not one of steady improvement in the nation’s public finances. Instead, it shows two years of unforgiving deterioration:

This is the history of French fiscal irresponsibility that S&P had in mind when they issued their ‘enough is enough’ warning on October 17.

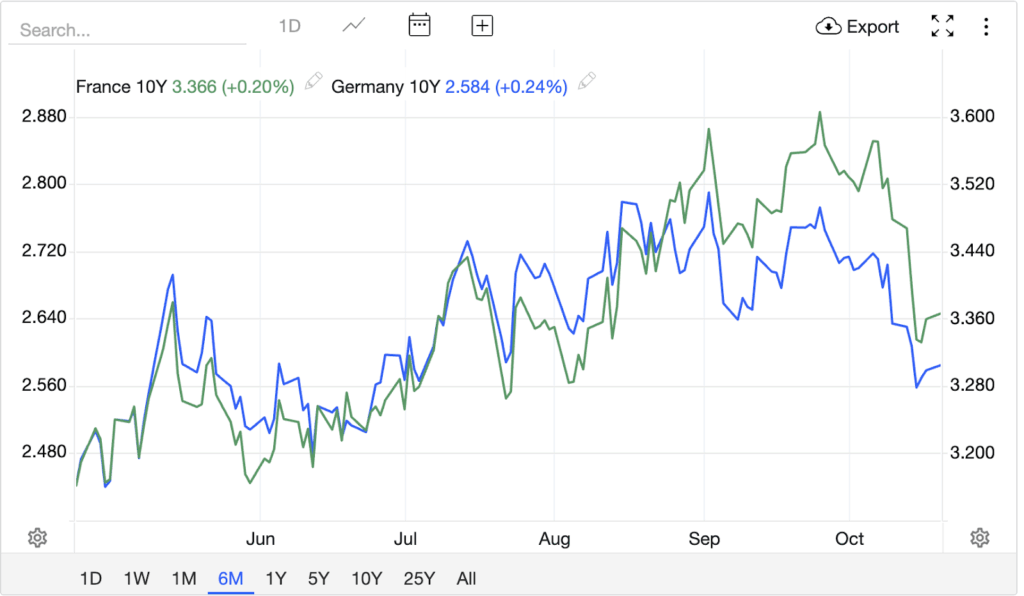

They are not the only ones reaching the end of the rope with France. Figure 2 reports, courtesy of TradingEconomics.com, the yields on the French and the German 10-year government bonds over the past six months. Up until September, the two yields were essentially equal, even showing a slight French advantage, with the yield occasionally dropping a smidge below the German yield.

Since September, the French yield has consistently exceeded the German yield:

Figure 2

The French-German yield margin is a risk premium that investors in sovereign debt now demand in order to continue to buy French government debt. It is noteworthy that this premium has emerged relative to German sovereign debt: the political leadership in Berlin has not exactly shown excellence recently when it comes to managing public finances.

Together with the S&P downgrade, this risk premium is a forceful indictment of the French government’s—or successive governments’—ineptitude. It is an indictment brought not by politicians with an ideological agenda, but by the free market and the private sector. If France’s political elite does not get its act together, form a sustainable government, and immediately begin fiscal consolidation, then both France and Europe will be forced to relive the fiscal crisis from 15 years ago.