As I have been reporting in abundance, the European Union is deeply troubled by weak public finances. Government deficits and debt are at unsustainable levels, and economic growth is not going to fix the problem.

A commonly proposed ‘remedy’ for budget shortfalls is to raise taxes. To make the idea more palatable to voters, it is sometimes sold as a ‘tax-the-rich’ scheme. Since economies tend to run out of the rich before those taxes have filled the budget gap, it should not be an option on any government’s to-do list.

However, we should not have to narrow the defense against tax hikes to just preventing tax-the-rich ideas from moving forward. We should keep a broad defense line against any attempts at raising the cost of government. Generally, Europe is already so heavily taxed that there is simply no economic room for more; every new proposal for higher taxes is a painful experience against the backdrop of just how much of the economy is gobbled up by government.

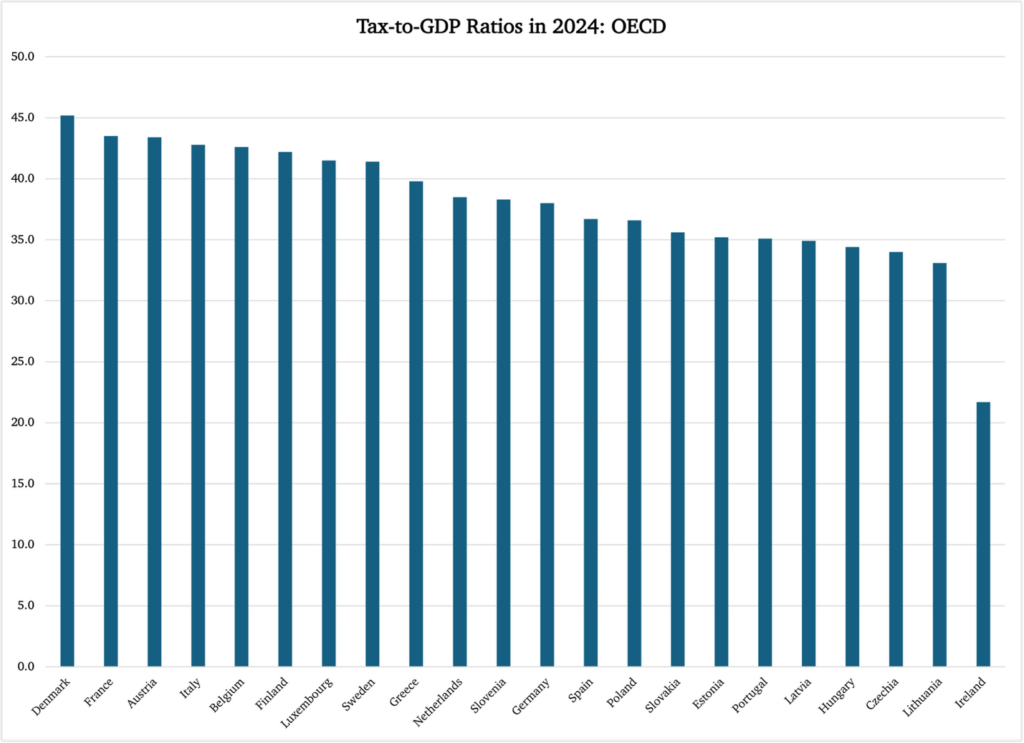

Figure 1 reports the figures from the OECD’s recently released overview of tax revenue for 2024. The countries reported here are the OECD’s EU members (not all EU members are in the OECD):

Figure 1

The OECD report is for the most part a depressing read, with taxes being at record levels in many countries. The bright spots are few, but as we will see in a minute, they do exist.

Based on the numbers in Figure 1 and on the lack of meaningful debate about taxes in Europe, it is easy to get the impression that high taxes are some kind of law of nature. They are not; high taxes are an ideological choice, emanating from socialist political victories.

As shown by the historic overview of taxes in the OECD report, the socialist view that big government is good government has dominated fiscal policy across Europe for the past several decades. However, before we compare historic numbers to those reported in Figure 1, it is worth remembering that taxes do not constitute 100% of government revenue. Every sovereign power that takes itself seriously has invented multiple sources of non-tax income, first and foremost in the form of fees and charges that citizens have to pay for specific services.

I mention this only as a reminder that the tax-to-GDP ratios reported by the OECD may seem a tad low to the trained eye. That is because they are, especially in the highest-taxed countries. There is a tendency in fiscal policy to transfer the collection of government revenue from taxes to fees and charges of various kinds; whenever a government has raised taxes as high as people find tolerable, it introduces fees and charges as supplemental revenue.

A common example is a government-run health care monopoly. Once the taxes that pay for the health care system have reached the highest level tolerable to taxpayers and voters, government shifts funding emphasis to fees that patients have to pay for various interactions with the health system. Another popular example is an application fee for permits, e.g., to register a business.

To take an American example: when the state of Colorado met resistance to raising the gasoline tax, it simply circumvented the political obstacles by adding a ‘fuel fee’ on top of the motor vehicles fuel tax.

In fairness, though, there is also a positive side to the distinction between taxes and fees. Taxes are a ham-fisted form of revenue collection, clumsily burdening large swaths of economic activity—employment, investment, consumption, property ownership. Fees, on the other hand, usually burden only those who use a specific government service (though the Colorado example shows that this is not always the case). As a general point, therefore, it would be preferable if government financed itself with fees to a larger extent and relied less on taxes.

With that in mind, let us compare the 2024 tax-to-GDP ratios from Figure 1 with the same ratios from 1965. The sample of countries will be smaller since some of the current 22 OECD and EU members were part of the Soviet empire in 1965 and therefore could not join the OECD.

The message in Figure 2 is eye-opening. Only one of these 14 countries has not raised taxes over the past six decades:

Figure 2

The numbers from Figure 2 raise two questions:

The answer to the first question is hard to define; neither the Right nor the Left has a straightforward answer. As for the second question, though, I do hope we can universally agree that such a limit does exist—somewhere.