Dramatic things are happening in the markets of government debt.

Normally, most people shrug their shoulders at a sentence like this, thinking that it does not affect them. On a regular day, that would be the right attitude: terms like ‘debt yield’ and ‘inflationary expectations’ are usually for economics and finance nerds.

Today, that is not the case, and that is good news.

Before we get there, though, let us recognize that Europe is still facing a recession. There is a wave of pessimists out there who predict a recession this year. I am one of them—in fact, I predicted already in December, before anybody else, that Europe would go into a recession this year. I have not changed my mind on that point, but—and here comes the good news—the recession might not be quite as bad as it looked back in December.

The good news has two components: inflation and debt yield. The former term is familiar and well-understood, but the latter may not be as obvious. It refers to the interest rate that governments pay people who buy their debt, i.e., their treasury securities. Debt buyers, or investors, are normally paid a coupon yield as compensation for their willingness to make the investment.

The coupon is related to the purchasing price of the security: if we pay $100 for it and the annual coupon is $4, we earn a 4% interest, or yield. Normally, the yield is higher the longer we invest the money, but as I explained recently, that is currently not the case when you buy debt issued by the United States government. The U.S. debt market, namely, is currently stuck in a so-called inverted yield curve, where the yield is higher if you buy short-term securities instead of long-term ones.

Inverted yield curves often raise alarms among professional investors. On any other day, I would agree, but in times of high inflation, the inverted yield curve is actually a bearer of good news. It means that investors believe that both inflation and yields (interest rates) are on their way down.

Those expectations are at work in the U.S. economy, and they are emerging in Europe as well. This means that the coming recession will in all probability be milder and shorter than it otherwise would be.

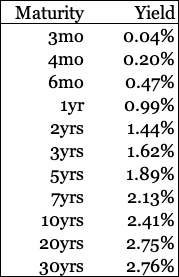

To see how this works, let us first look at the yield curves for U.S. government debt and for equivalent euro-denominated debt. To start with, let us look at the yields on euro-denominated treasury securities from September 1 last year (a randomly chosen date):

Table 1

This selection of euro-denominated government securities shows a normal distribution of yields: long-term maturities pay more than short-term ones.

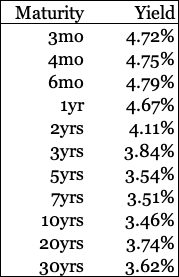

By contrast, here are the yields on U.S. Treasury securities from January 25th this year:

Table 2

The U.S. yield curve is inverted—not perfectly, but close. When you get 4.72% on an annualized basis for buying 3-month bills, 3.84% per year for a 3-year note, and 3.62% on a 30-year bond, normal market logic is tossed aside. In times of high inflation, the yield inversion is a reason for all of us to smile.

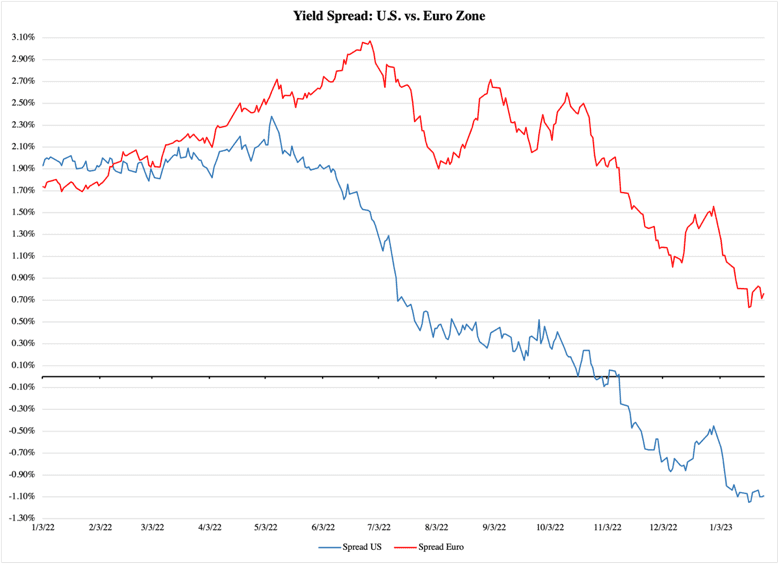

America has had an inverted yield curve for three months now, but the euro zone has not yet reached that point. Figure 1 illustrates this with two functions, representing the yield curves for both economies. The curves measure the percentage point difference between the longest and the shortest maturities. In the euro-zone example from Table 1, this means: 2.76 – 0.04 = 2.72. Using this calculation for daily debt yields, the red function in Figure 1 reports the shape of the euro-zone yield curve from early January 2022 to the end of January 2023. The blue function reports the corresponding information for U.S. debt securities:

Figure 1

The U.S. yield curve was positive and stable up until early June last year. This means, again, that the longest-maturity government security—the 30-year bond—paid more than the 3-month bill, and that the difference was stable over time.

In the middle of the summer last year, the yield curve started to change. The long-short yield difference became smaller and smaller, until one day in early November it flipped. Suddenly, it paid more to own a short-term U.S. government security than a long-term one.

The euro-zone yield curve remains positive, but it follows the U.S. curve downward. If this trend continues, which is likely, it will eventually flip negative as well.

What is the good news in this?

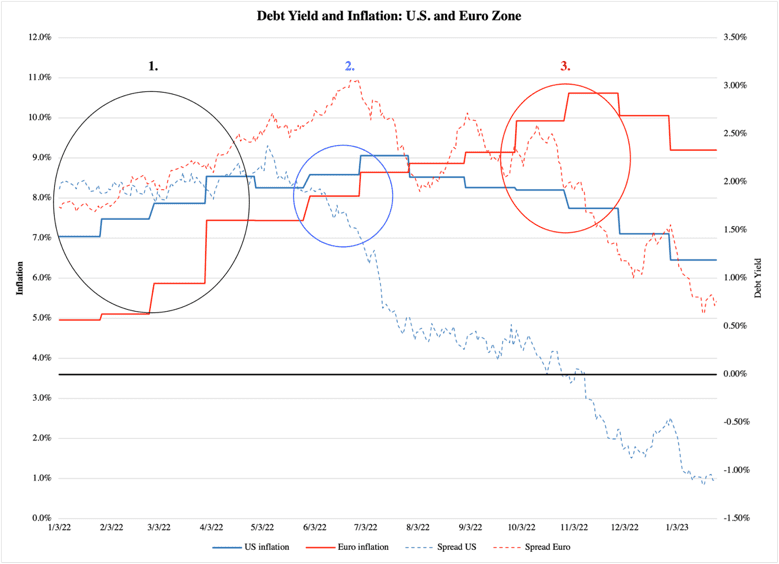

To answer this question, let us bring inflation into the picture. We start by toning down the functions from Figure 1, making them dashed and less visible in Figure 2. The colors are the same, with blue for America and red for Europe.

Then we add inflation, reported by the staircase-shaped functions. Since inflation is measured monthly, while the statistics on debt yield is updated daily, we get these oddly shaped inflation functions in Figure 2. There are three exciting points to pay attention to:

Figure 2

1. Early on in 2022, inflation was on the rise in both economies. The yield curves were stable and positive in the sense that the margin between the longest and the shortest maturities remained constant.

2. In the summer, something happened on the American side. The inflation rate was still rising, but at a much smaller pace. As that happened, the yield difference between the longest and shortest maturities began shrinking. Very soon after that, inflation peaked and started declining.

3. The same thing happened in the European economy, and in the same order: first, the yield difference started shrinking, then inflation peaked and started to decline.

The magic word here is expectations. When the yield difference between short and long maturities gets smaller and eventually goes negative, it means that:

a) investors expect lower inflation in the somewhat distant future, and are therefore ready to accept lower yields on long-term investments; however,

b) they also expect inflation to remain elevated in the short term and therefore demand higher yields to buy short-maturity government securities.

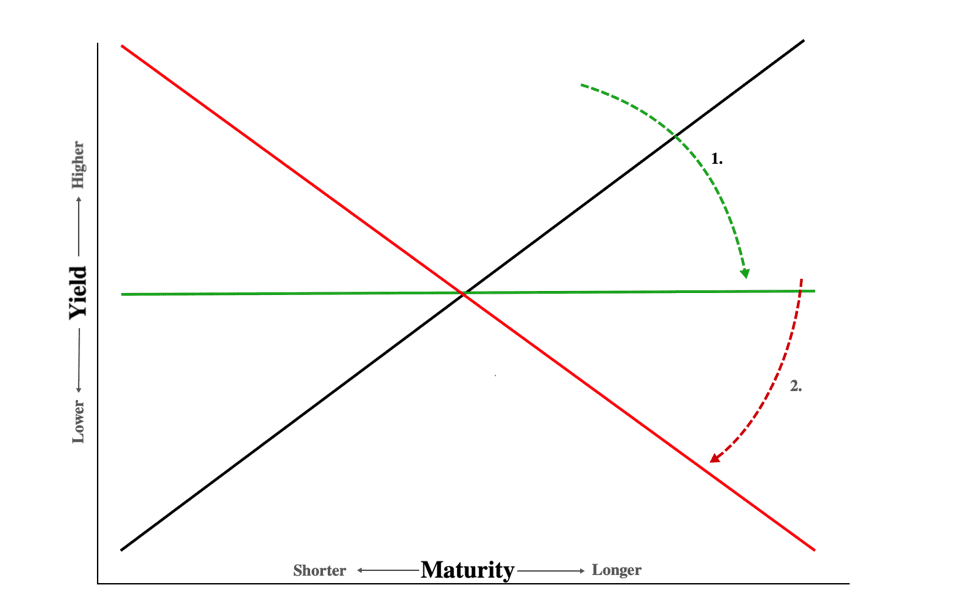

Let us review that one more time, in a different format. In Figure 3, we start with the black yield curve, which is a normal one with a higher yield on longer maturities. When investors begin to expect that inflation will fall at some point in time but remain elevated in the short run, they accept lower yields on long-term securities.

As they concentrate their investments on the long end of the maturity spectrum and buy bonds that are valid for several years, there is a simultaneous decline in demand for short-term securities. This causes a rise in yields on short maturities—hence, the swing (1) from the black function to the green:

Figure 3

With more and more investors growing confident that inflation will soon reach its peak, the shift in investment demand from short to long maturities—e.g., from 1-year bills to 5-year notes—is reinforced. Eventually, the yield curve becomes inverted (2).

The 1-2 sequence in Figure 3 is good news when inflation is high. As households and businesses grow more confident that the future is going to be more affordable than the present, they will eventually respond by increasing their economic activity. It usually takes longer for people to deliver on their improving expectations than it does for them to cut spending when expectations are pessimistic, but when they do increase spending, the improvements in the economy as a whole are substantial.

But wait: if the yield curve is already negative in the U.S. economy, and if it is on its way there in Europe, why do we still predict a recession?

There are two reasons for this. The first has to do with the horizon of inflation expectations. As is evident from Figure 2, inflation is still elevated in both America and Europe, and it is only leisurely falling back to the 2-2.5% range. In fact, European inflation has barely begun to retreat. A reasonable estimate is that it will take until next fall before inflation rates return to ‘normal’ levels. It could go faster if a recession sets in with full force, but unless the euro zone economy is thrown into an unmitigated depression, the six-month horizon is reasonable.

Since inflation is going to remain elevated for the first half of 2023, consumers and businesses will remain cautious and prudent about new spending for the same period of time. However, a decline in longer interest rates—again the result of an inverted yield curve—will make new installment loans for homes, cars, etc., more affordable. Given the caution among consumers, the stimulative effect on the economy from this affordability will be modest at first but pick up speed as the recovery gains momentum.

With stronger consumer confidence, low interest rates on consumer credit will help consumers make new spending commitments earlier than they otherwise would. This in turn helps the economic recovery get underway, alleviating an otherwise potentially serious recession.

In other words, we can expect a recession in Europe because the positive effect of lower inflation and lower interest rate will be delayed. It will not kick in until consumers feel confident enough to commit their hard-earned money to installment loans and to regularly being able to pay their credit card bills. All recession bells will go off in the next couple of months, but the recovery could begin as early as in the fall.

This scenario is contingent on the usual ‘all other things equal’ assumption. Economists happily hide behind it in an attempt to get away with a bad forecast ‘for free.’ Since I do not do bad forecasts, I am not going to use that escape hatch. Instead, I am going to point to the second reason to expect a recession: fiscal policy.

European governments generally have serious problems with debt and budget deficits. These problems were never really solved after the Great Recession in 2009-2011: most countries across the euro zone have been limping along with their government finances, struggling to meet the EU’s stringent fiscal requirements of a deficit below 3% of GDP and a debt at no more than 60% of GDP.

The 2020 pandemic and its artificial shutdown of economic activity poured quite a bit more gasoline on the public debt fire. As of the third quarter of 2022, nine of the EU’s member states ran budget deficits in excess of the 3%-of-GDP threshold, and in 13 countries government debt was higher than 60% of GDP.

As the economy goes into recession, tax revenue falls and government spending increases—due to more unemployed individuals qualifying for entitlement benefits—which leads to deteriorating public finances. There is a significant risk that the governments in the nine countries with excessive deficits respond by raising taxes and cutting spending, i.e., austerity measures, which will exacerbate the recession. If the 13 excessively indebted countries (some of which also have excessive deficits) resort to austerity, the continent-wide repercussions are certain to pull down the whole of Europe.

Austerity policy is really the only factor that can overwhelm the positive outlook presented here. That makes Europe’s legislators at least partly responsible for mitigating, not aggravating, the coming recession.

Let us hope that they are capable enough to handle that responsibility.