There is good news and bad news about inflation.

The good news is that the worst of it is now in the past. While the February numbers from Eurostat show that the decline is slow, Europe is nevertheless following America on the path back to low inflation rates.

The bad news is that once this episode is over, it may not be long before inflation erupts again. The reason is found in one term: institutionalized egoism.

Inflation is a man-made phenomenon, caused almost exclusively by an irresponsible combination of bad fiscal and monetary policy. When allowed to reign for too long, the bad policies not only change the economy in the short term but also alter its very structure over the longer term.

At the core of the bad policies is our welfare state, whose unending benefits programs have brought about a permanent expansion of government. These programs

To fund the benefits we cannot afford to pay for, we borrow money from future generations. The structural budget deficit, which is inherent to the welfare state, becomes a permanent tax on the shoulders of our children and grandchildren. The fact that this deficit exists in both Europe and America, shows that we believe that our wants and needs are more important than those of younger generations, born and unborn.

In terms of a legacy for posterity, the taxes to pay for our debt is bad enough. However, our impact on the future does not stop there. In the past 10-15 years, governments in both America and Europe have increasingly funded our generational egoism with newly printed money. Over time, this so-called deficit monetization has pumped so much liquidity into the economy that it finally lit the fuse of monetary inflation.

While energy prices have been high, they have not been extreme enough to cause an extended period of economy-wide, double-digit inflation. To the extent we have had supply-chain problems, they have not been economic in nature. It is statistically proven beyond the shadow of a doubt that money printing is behind the current inflation episode.

Therefore, we also know how to avoid it in the future: print less money. The problem is that in order to permanently reverse our monetization of budget deficits, we need to first rid ourselves of our generational egoism. This starts with the recognition that the Federal Reserve in America, and the ECB in Europe, started printing money not out of intrinsic recklessness, but because they were backed into a corner by the irresponsible legislators who created the welfare state.

Once we recognize our role in creating inflation, we can reform away our generational egoism. We can start by eliminating entitlements currently paid out to the gainfully employed for no other reason than economic redistribution. If we do this, we have come a long way toward closing our structural budget deficits. The outlook for such reforms has been dim in the past, but new contributions, both theoretical and practical, could change that.

Until we get our reform programs going, we have to live with the fact that our central banks will soon have to return to massive money printing just to finance the structural deficits in our government budgets. In doing so, the central banks will maintain the structures that keep economic growth at historically low levels.

Put differently: we will need a permanently looser monetary policy in the future than we have seen in the past just to maintain full employment and our current standard of living. This, in turn, means a permanently elevated risk for more inflation.

The other side of that inflation-risk coin is that we will soon return to lower interest rates. They will be instrumental in keeping the economy at full employment, thereby keeping tax revenue as high as possible. That still won’t be enough to pay for the welfare state, given the economic burden of modern welfare states that consumes 40-50 percent of the economy.

None of this is news, really. The Federal Reserve has actually admitted at least the first part of this analysis. They are very well aware that they will soon have to return to printing more money. Yes, the Federal Reserve, which is leading the central-bank crusade against high inflation, has admitted that monetary policy must be permanently looser (technically more accommodating) in the future. In their monetary policy report for the first half of 2023, they bluntly explained that

the level of the federal funds rate consistent with maximum employment and price stability over the longer run has declined relative to its historical average.

As far as I have been able to tell, I am the first analyst of U.S. monetary policy to pick up on the dynamite embedded in this statement. This is surprising given that there is ample statistical evidence to prove that the Federal Reserve is correct. That evidence applies to Europe and America alike.

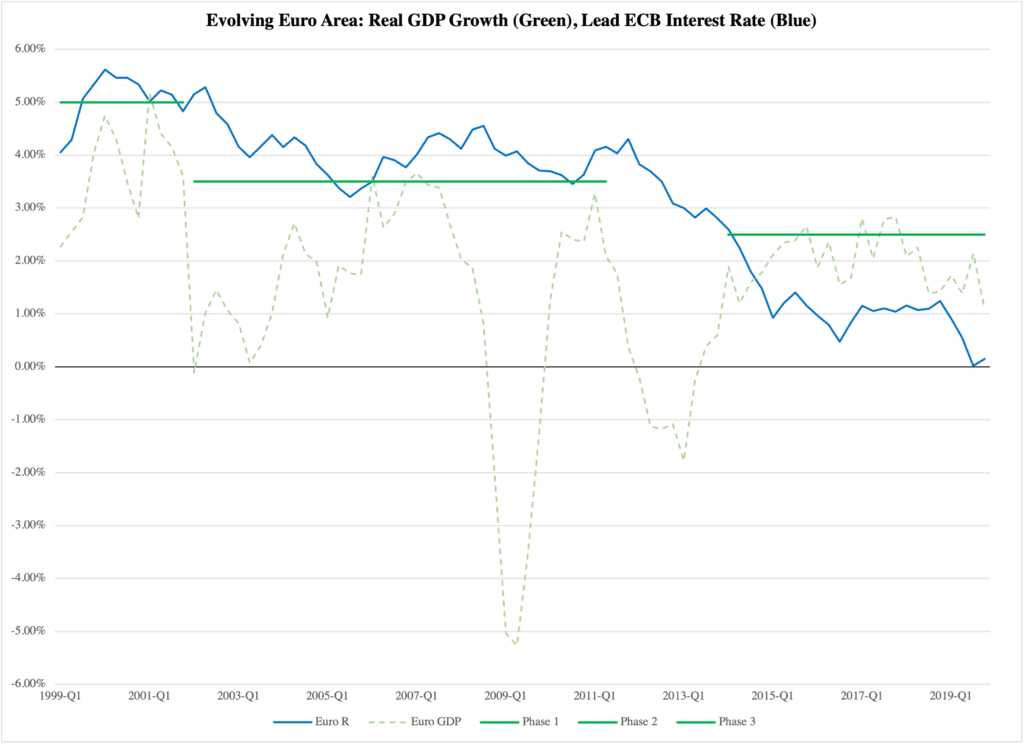

Europe first. Figure 1 looks at the rate of real economic growth in the euro zone from 1999 through 2019. (High growth is necessary for full employment.) The pandemic and its aftermath are excluded in order to focus on the long-term trend in the economy. The slow interest-rate decline (blue function in Figure 1) is accompanied by an equally compelling decline in GDP growth:

Figure 1

Figure 1 marks three phases of GDP growth, the first covering the years around the millennium shift. During this phase, the economy manages to top out its growth rate at 5% (adjusted for inflation, of course). The average growth rate during this phase was 3.7% per year.

In the next phase, which runs from 2002 through 2007, the euro zone economy has a hard time reaching 3.5% growth in its top years. The average rate has now fallen to just a hair below 2%. The same average applies to the third phase, which starts in 2014 and runs all the way to the end of 2019. Here, though, the top growth rates barely exceed 2.5%.

While GDP growth slowly declines, the ECB’s lead interest rate averages 5.07% in phase 1, 4.11% in phase 2, and 1.1% in phase 3.

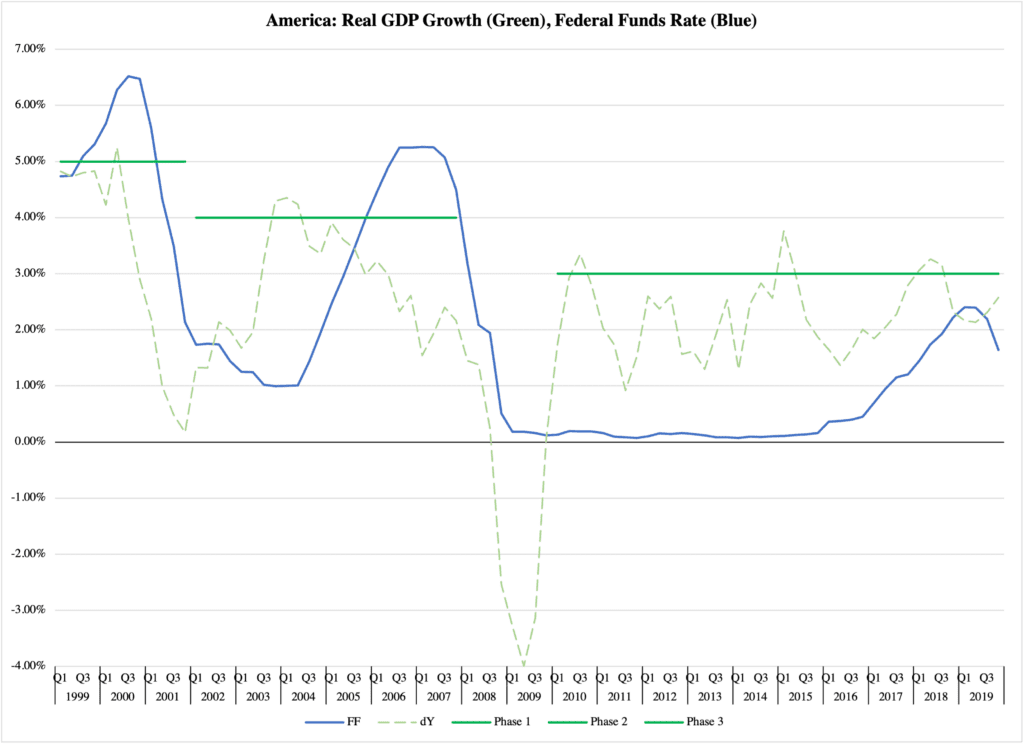

We see a similar, only more pronounced pattern in the American economy:

Figure 2

Sources of raw data: Bureau of Economic Analysis (GDP), Federal Reserve (Funds Rate)

In the first phase, from 1999 through 2001, a growth rate of 5% is still attainable at the cusp of the business cycle. Thanks to the millennium recession, the average growth rate for this period is 3.3%. In the next phase, 2002-2007, the economy barely tops 4% when doing its best; on average, it hums along at 2.8%.

During these phases, the Federal Reserve’s lead interest rate, the so-called federal funds rate, averaged, respectively, 5% and 2.9%.

Phase 3 is extreme, but only when viewed in a historic context. Averaging 2.25% per year, the U.S. GDP only managed to exceed 3% in a single quarter here and there. These numbers were combined with an average federal funds rate of only 0.6%.

A declining interest rate is tantamount to the central bank growing money supply faster than the economy can absorb—and make good use of—that new money. The result is twofold:

Economists faithful to Austrian theory point out that artificially low interest rates lead to an overallocation of economic resources to the present and an underallocation into the future. This is a valid point, but we won’t see the whole picture unless we include the role government plays in this intertemporal misallocation. With government budgets being the transmission mechanism from excessive money supply to full employment at very low interest rates, government becomes both a culprit of structural distortion of economic resources and of high inflation.

That said, it is also important to acknowledge that the artificially lowered interest rates help the private sector grow bigger than it would if rates were high—and government the same size it is today. Businesses are encouraged to invest on cheap credit, but more importantly: consumers are encouraged to spend more borrowed money.

Low interest rates do not have a very strong effect on business investments, although, on the margin, they can make a difference. It is less risky to take out leveraged loans (loans financed by loans) and thereby less risky to engage in more speculative investment activities. That does not necessarily mean more economic growth: the return on more speculative investments tends to come in the form of capital gains, not a future stream of income. In other words, profit expectations are tied to asset value inflation, not a strongly growing economy.

By contrast, low interest rates appear to have a clearly visible stimulative effect on consumer spending. There is no more damning example of this than Sweden, an economy over which I recently penned an obituary. In the past ten years, Swedish households have effectively paid for 26% of their consumer spending with new credit. In 2021, that ratio reached 42%, the highest in Europe after Luxembourg.

While a lot of that borrowing has gone toward mortgages, it is not obvious that the borrowed funds have gone toward buying a home. With the extremely low interest rates in the past several years, to some degree led by zero or negative central-bank rates, consumers have used the free market value in their homes (created by equity price inflation) to take out a second mortgage and spend the money on consumption.

Sweden is extreme in this case, but the phenomenon of living on credit is more widespread than that. The problem, of course, is that debt-driven consumption comes with future payment obligations, which have to be covered by income earned in the future. Those debt payments eat into household income without creating any new, current economic activity. Just like a government that tries to pay off its debt by raising taxes, a household trying to climb its way out of a debt hole will reduce growth-creating economic activities today, to make up for growth-creating activities yesterday.

Taken together, our efforts to redeem past debt sins depress economic growth. This depression comes on top of the depression of economic growth created by an excessively large welfare state.

I am not going to go as far as to say that the Federal Reserve, in stating that we need lower interest rates in order to keep the economy growing, has run through this entire economic analysis. I hope they have, but I also know how the modern economics profession works: they look a lot at statistical correlations, and not a whole lot at the causal patterns behind the results they get.

For this reason, I also doubt that economists beyond the Federal Reserve have done any analysis of the same structural nature outlined here. This leads me to be pessimistic about policy reforms to help us avoid the future that the Fed outlines in its statement on full employment and interest rates. I hope my pessimism lacks merit, and I do see faint glimmers of hope that the conservative movement is getting ready to transform theory into practice.

If we can do this, we will not only prove that we stand on the firmest of ideological grounds, but also improve the conditions of living for coming generations. If we can part with our own generational egoism, we will create a better world for generations to come.