In the 1950s, the Swedish government started gloating globally over its ongoing socialist transformation of the country. In 1960, renowned Swedish economist and socialist dogmatic Gunnar Myrdal published a book where he claimed perennial victory for the Swedish experiment in ‘democratic socialism.’

Meanwhile, Hungary was held back by the coercive forces of the Soviet system. It was not until the Communist empire ended 35 years ago that the Hungarians could begin to chart their own course into the future.

Since then, Hungary has tried different models, including an attempt at copycatting the Swedish model. There were some successes, including moderate economic progress. But it was not until Fidesz decisively won the 2010 election that the Hungarian economy really took off.

Despite remarkable gains in GDP per capita, household earnings, foreign direct investment, and just about every other major economic variable, the Hungarian conservatives are rarely acknowledged for their success. Foreign dignitaries in general, and Swedish ones in particular, have a penchant for lecturing—even lambasting—the Hungarian government.

Since the Swedes have merrily taken a lead in the international finger-pointing at Budapest, it is only fair to see what the hand attached to that finger has managed to produce back in its own country. A side-by-side comparison between Sweden and Hungary is revealing. It is also relevant, given how the virtue dispensers in Stockholm perpetuate the social democrat attitude from the last century by looking down their noses at countries like Hungary.

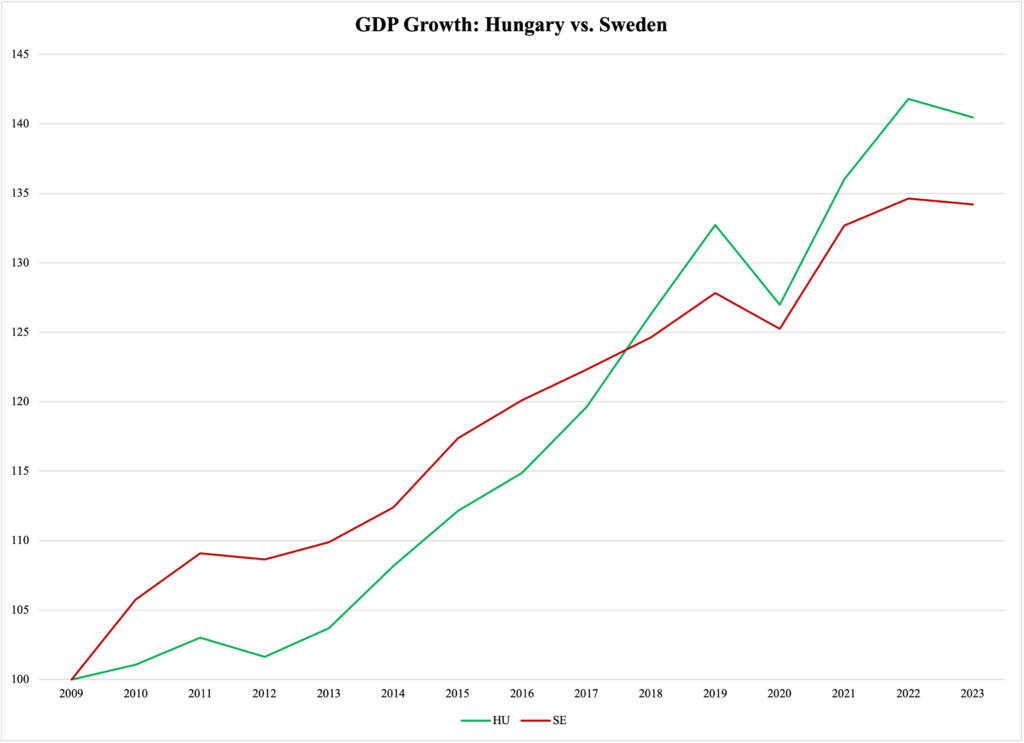

First and foremost, the Hungarian economy has been a European leader in GDP growth over the past 15 years. From 2010 to 2019, the period when Fidesz rolled out its economic program for a more prosperous future, the Hungarian economy grew by an annual average of 2.9% (adjusted for inflation). Sweden mustered only 2.4%.

The comparison becomes even more compelling if we concentrate on the 2015-2019 period, the latest with synchronized global economic growth. During those years, Swedish GDP expanded by 2.6% per year, while the Hungarian economy averaged 4.2%.

Figure 1 illustrates the comparative Hungarian economic success in the following way. Suppose you deposited €100 in a bank account named “Sweden” and the same amount in a “Hungary” account. Suppose the annual interest was equal to the real yearly growth rate in the respective economy. By 2019, the Hungarian account would be worth more than the Swedish account; just to show that the trend did not end there, Figure 1 extends the time series to 2023:

Figure 1

I have on occasion discussed the Hungarian economy with Swedish economists and politicians. One of their favorite counterpoints to the argument in Figure 1 is that Hungary is so far behind Sweden in GDP per capita that it is not even meaningful to compare the two.

Figure 2 refutes this point. Using United Nations National Accounts data—a lesser-known but very useful database—it reports Swedish and Hungarian GDP per capita as a ratio, both converted to U.S. dollars. There is no doubt that in the 1990s, Sweden was leaps and bounds ahead of Hungary, initially with a per-capita GDP about nine times higher than in Hungary.

Over time, the Hungarian economy has elevated the standard of living of its population at an increasingly respectable pace. In fairness, it was easy to do so during the transition from central economic planning to a market-based system, but that period ended somewhere in the mid-2000s. By the time Fidesz came to power in 2010, it would take a whole new level of macroeconomic prowess to continue elevating the living conditions of Hungary’s families.

It worked. Once the aftermath of the 2008-2010 recession was over, the future-focused conservative government in Budapest took the nation’s economy to a whole new level. Figure 2 divides the Swedish GDP per capita with the Hungarian equivalent, both measured in the same currency (U.S. dollars). In 1990, Sweden had a GDP per capita of $30,551, while Hungary was at $3,583; the Swedish one was 8.5 times bigger. Fast forward to 2023, the Swedish GDP per capita was only 2.5 times the Hungarian one:

Figure 2

If the current conservative government can continue its successful economic policies, Hungary will pass Sweden in GDP per capita before 2030.

Another argument I often hear about Hungary from Swedes in general is that the conservative reforms to the welfare state have proverbially trapped women in their homes. Hungarian women, the argument goes, do not work to nearly the same degree as Swedish women do.

It is a fact that Swedish women participate in the workforce to a higher degree (82%) than Hungarian women do (74%). However, this is not necessarily to Sweden’s advantage. First of all, Swedish women may be participating in the workforce to a higher degree, but their chances of landing a job are not as great as those of their Hungarian peers. In 2024, 91.4% of the women in the Swedish workforce in the age group 15-64 were employed. That same year, 95.6% of Hungarian women in the same age group had a job.

Since the numbers were very similar for men, the official unemployment rate for Sweden was 8.5%, compared to Hungary’s 4.5%.

Beyond the higher Swedish unemployment rate, the question is what the socio-economic consequences are of maximizing women’s workforce participation. Is it really in the interest of the children that both their parents work?

The Swedish welfare state is designed to encourage both parents to work, even when they have very young children. After a year of parental leave benefits, Swedish children are typically rushed to the nearest daycare center, where they spend their parents’ full-time-plus-commute workdays. The ultimate goal is twofold: to minimize economic differences between ‘rich’ and ‘poor,’ and to maximize tax revenue for the welfare state.

By contrast, the Hungarian welfare state is based on a conservative architecture. It is focused on the family as the cornerstone of a civilized, prosperous society. The two-fold goal is to enable the organic formation of social cohesion and motivate parents to have more children.

These two sharply contrasting visions for the welfare state are important when we look at labor market statistics. Hungarian women undoubtedly use the resources available to their families in order to allocate more time to their parenting than Swedish women. With its economic policies in general, the Hungarian government therefore strikes an intelligent balance between two socio-economic needs: a strong, skilled, and highly productive workforce, and strong, thriving families.

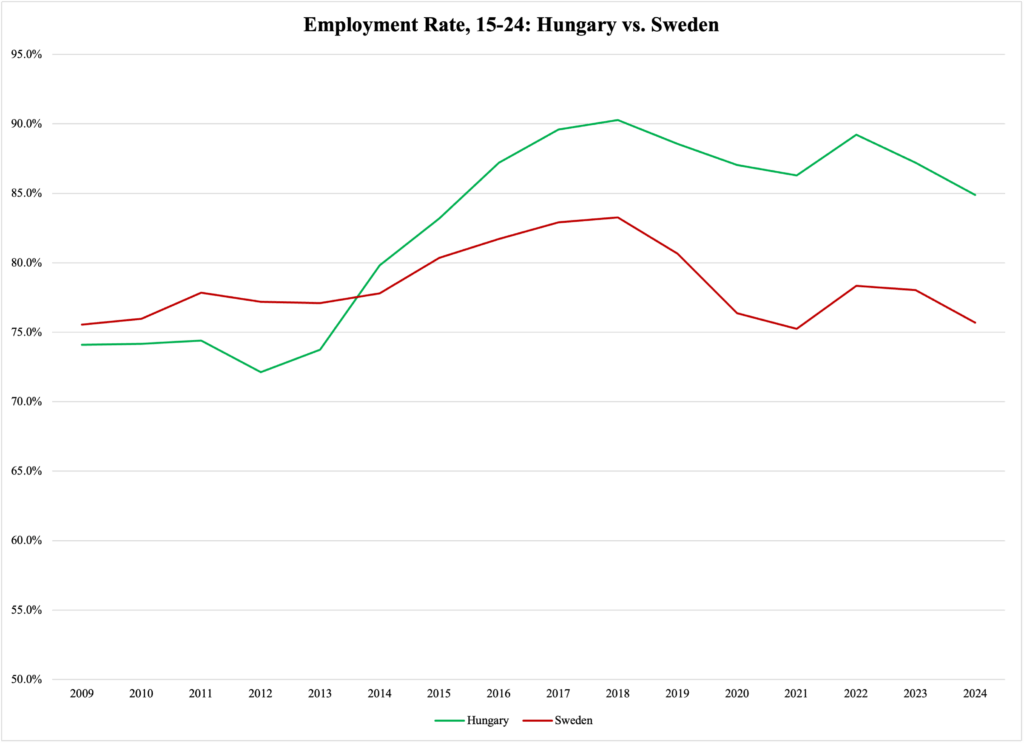

With that said, it is striking that the Swedish welfare state, aiding and abetting workforce participation as it does, seems to only feed new workers into unemployment. This is especially true when it comes to workers aged 15-24. Figure 3 reports their employment rate:

Figure 3

When it comes to macroeconomic performance, Hungary has an impressive record that should inspire other countries—especially Sweden. Rather than dispensing pretentious moral dogmas on how the Hungarian welfare state supports families, the Swedish government should ask, first and foremost, what it can do to improve economic growth, bring down unemployment to Hungarian levels, and how it can reduce crime and other problems plaguing Swedish society.