Hungary has one of the strongest economies in Europe. The latest unemployment number, 4.1%, is impressive, and so is the trajectory of government finances: the structural deficit that plagued the Hungarian government’s budget for so long, has almost been eliminated.

The only real problem is high inflation. In December, Hungary led Europe with its 25% and was one of only three countries where inflation has not yet peaked. This rate is troubling but also still manageable. It is unlikely to climb much higher, but economic theory also prescribes that once inflation reaches a certain level, it tends to become a self-perpetuating phenomenon. People start taking the rapid growth in prices for granted, writing it into all sorts of economic contracts.

Hungary does not exhibit any signs of having crossed the self-perpetuating line, but there are also no signs yet that inflation is close to its high point. Furthermore, even when it peaks, given the high level it is at currently, it will take quite a bit of time for the economy to “believe” that inflation is declining.

The longer an economy has to deal with double digit inflation, especially at the levels that Hungary and a few other countries in the EU currently have, the more harmful the inflation level becomes. Therefore, the Hungarian government is well advised to set other priorities aside and, in the coming months, focus all its economic policy on reducing inflation.

This will not be a problem. The government in Budapest has consistently shown its economic policy skills, and their country is blessed with some of the best economists in the world. Furthermore, the policy changes needed are easier than most people think, at least from an economic viewpoint.

However, before we get to the solutions, we first need to understand what has driven Hungary to the top position inEurope in this less-than-desirable economic category.

To begin with, we must part with the notion that Hungary’s inflation problems are similar to those of other European countries. There are aspects to their inflation phenomenon that are unique to the country. Specifically, it is not reasonable to entirely blame the rapid price increases on high energy prices. All of Europe—and much of the world beyond its borders—is struggling with the bills to keep lights on, yet inflation rates vary quite a bit across the continent.

In other words, to find a way to reverse the rapid price increases in Hungary, we need to pinpoint the factors that make Hungary stand out.

Ironically, one of them is related to the economic success that Hungary has had in the past ten years. Strong economic performance across the board comes at a price; the causal chain from success to high inflation is a bit complex, so let’s unfold it slowly.

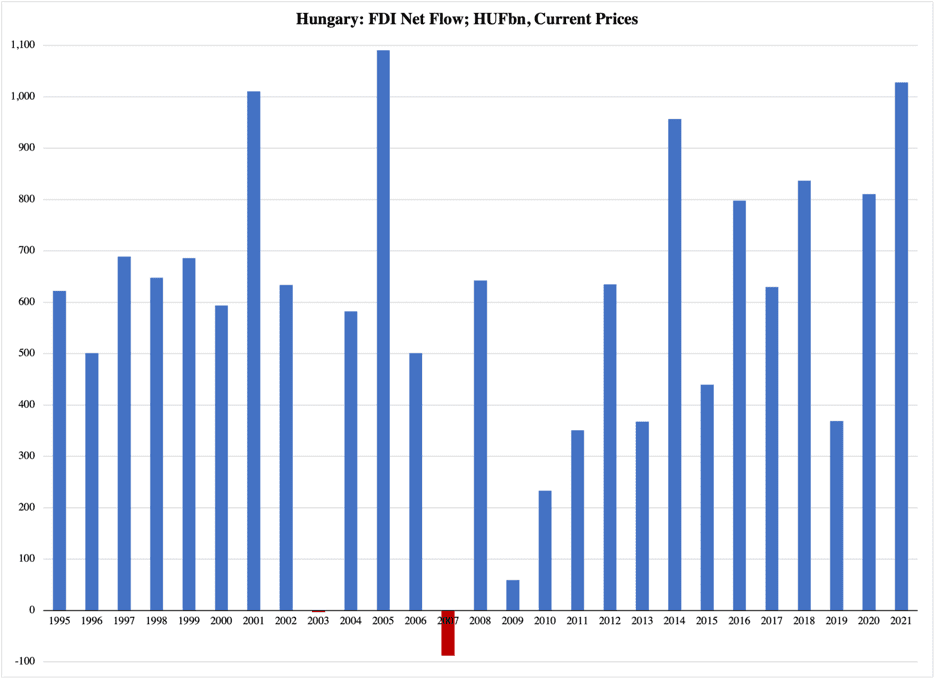

The Fidesz government has combined an intelligent tax system with welfare-state policies that promote economic and social stability. This makes Hungary an attractive destination for foreign direct investments (FDI). While capital started flowing into the country soon after the Soviet era ended in 1989, the flow was reduced somewhat when the Hungarians entered the European Union in 2004. Competition from other countries inside the union became notable.

The net inflow of FDI was suppressed further by the recession in 2009 and 2010. However, the conservative government that first took office in 2010 has worked relentlessly to improve Hungary’s competitiveness. As Figure 1 shows, the net FDI inflow (incoming investments minus outgoing investments) improved steadily from 2010 on, reaching one of its highest levels on record in 2021:

Figure 1

When foreign investors bring money to Hungary, they deposit their foreign currency with a commercial bank in the country. That bank takes the foreign currency to the Magyar Nemzeti Bank, or the Central Bank of Hungary, and receives domestic currency for it.

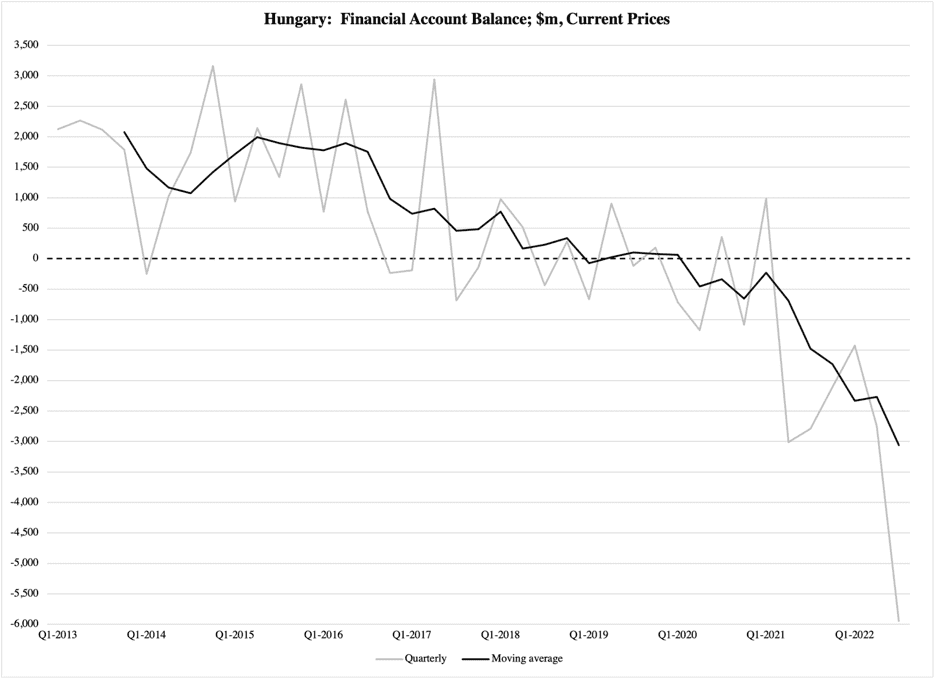

When more foreign currency comes into Hungary than goes out, the central bank accumulates a currency reserve. One of the exhibits of this accumulation is in the so-called financial account of transactions across Hungary’s borders. This account excludes trade in goods and services but includes most other types of transactions between Hungary and the rest of the world.

Figure 2 reports the financial-account balance (converted into U.S. dollars for data accessibility reasons). There was a surplus for almost the entire period 2013-2020:

Figure 2

The surplus leaves more foreign currency in the central bank’s possession.

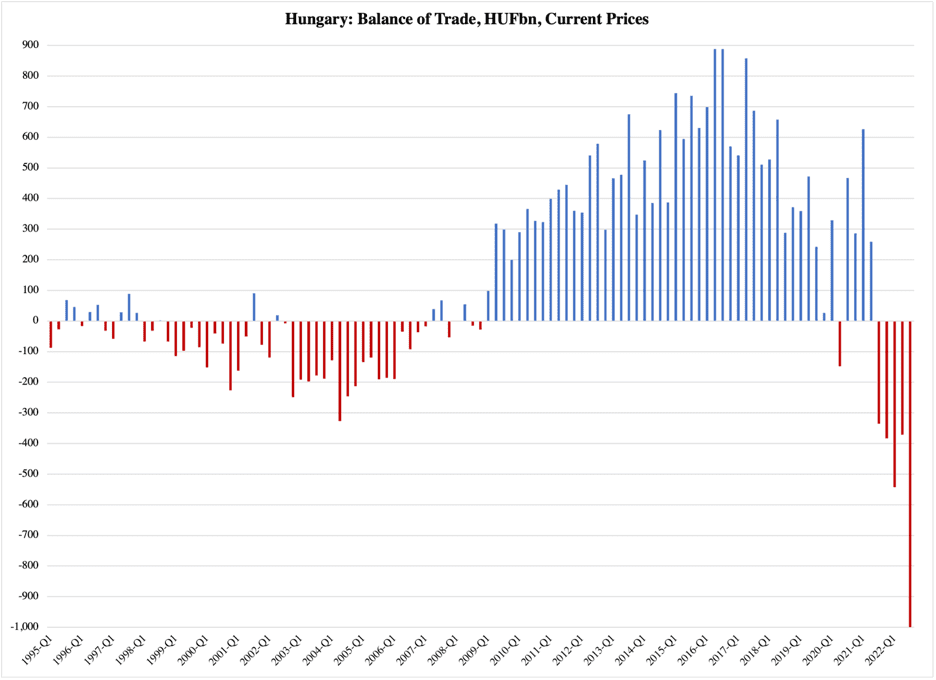

A surplus in the trade of goods and services works the same way. Hungary has run a substantial trade surplus for a long time:

Figure 3

It is interesting to note the correlation between the net FDI reported in Figure 1 and the trade surplus. It shows how foreign corporations make investments in Hungary and then export products from there. From a long list of examples:

The combination of foreign direct investments flowing into Hungary and a trade surplus from strong exports produces a substantial foreign-currency reserve; according to the Hungarian central bank, as of December last , they held the equivalent of €38.7 billion, almost 9% more than at the beginning of 2022.

So far, nothing has happened that would be a real inflation threat. The problem starts when the central bank exchanges the foreign currency for Hungarian forints. In doing so, the central bank increases its money supply; if this increase is faster than the growth of the country’s gross domestic product, GDP, the result is slowly building inflation pressure.

It is worth noting that money-driven inflation does not happen immediately. It takes some time, usually a few years, before the pressure built by a growing money supply actually leads to inflation. When it does, though, the rate rises faster than when other causes of inflation are at work (such as the economy operating at full employment).

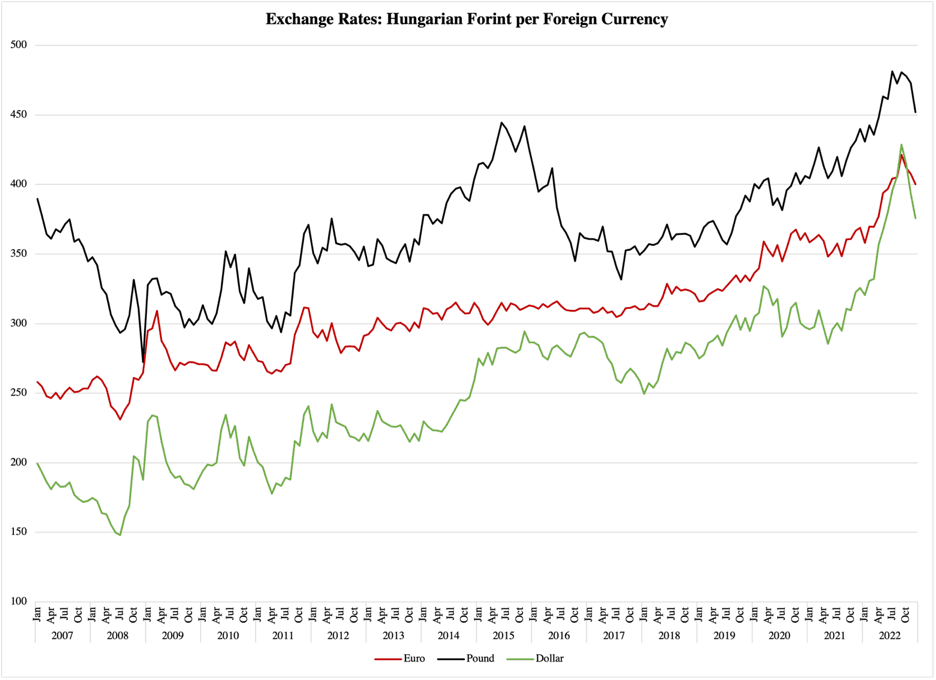

Rapid growth in the money supply shows up in many parts of the economy. One of them is the exchange rate of the forint vs. other key currencies. When a country’s trade balance and financial account are positive, all other things being equal, the currency gains value. Simply put, there is more demand for it than supply. However, Figure 4 tells us that the exact opposite has happened with the Hungarian currency:

Figure 4

The most reasonable explanation for this currency depreciation is that domestic money supply has outpaced the inflow of foreign currency. This modest but steady decline in the forint has helped companies that export from Hungary, but it has also, in itself, contributed to inflation by raising the cost of imported services and goods (including oil).

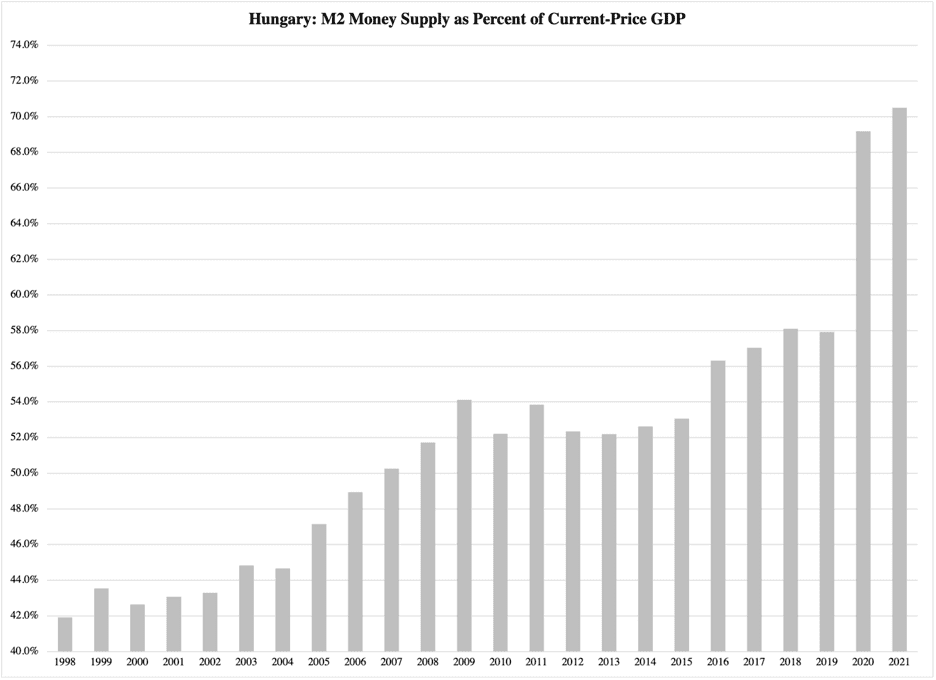

Now for the key question: has the money supply in Hungary outpaced GDP? Yes, it has. This means that the economy has a latent potential for monetary inflation.

Figure 5 shows the Hungarian central bank’s supply of money as a percentage of current-price GDP:

Figure 5

Hungary is not alone in this relatively gradual monetary expansion. Most central banks in the Western world have been on a money-printing streak in the past two decades. Up until three years ago, the monetary expansion had been just within the boundaries of what an economy can handle without runaway inflation, but with the extra cash infusions that came with the 2020 pandemic, there was, so to speak, no more room in the economy. Monetary saturation reached the point where it caused inflation.

The rise in inflation came fast, as shown by these numbers from Eurostat:

As mentioned earlier, in December 2022 the annual rate had reached 25%.

What can the Hungarian government do to bring inflation down again? The answer to this question has two parts, the first of which is related to energy prices. Just like every other country in Europe, Hungary has taken a beating from costly energy. That alone cannot explain overall high inflation, but it does of course contribute.

The best way to break the pattern of costly energy is to increase its supply. In Hungary’s case, this means increasing imports. Given the strong public opinion against the sanctions on Russia, it would make economic sense for the Orbán government to reopen Hungary to Russian sales of oil and natural gas.

Doing so would be very controversial, of course, especially in the EU. However, given the consequences of high inflation, those who wish for continued sanctions are morally obliged to provide a realistic alternative. If they can’t, the most rational move is to lift the sanctions and re-engage in energy-based trade with Russia.

The second part of the answer to what Hungary can do to curb its high inflation is to address the very problem outlined above: monetarily driven inflation. A key component of this would be a change to the Hungarian central bank’s exchange-rate policy. By introducing a fixed exchange rate, the central bank can cool off inflation in two ways:

One of the instruments that the central bank has is to use part of its foreign currency reserve to buy back some of its own currency. This reverses the foreign-currency driven part of the monetary expansion.

Currently, the central bank bases its soft exchange-rate peg on activities in the currency market. With a strict fixing of the exchange rate, the central bank would reverse the relationship and, instead, direct the conditions under which the market operates.

Since the forint has slowly depreciated in the currency market , a shift toward a fixed (or pegged) exchange rate will require higher interest rates—at least initially. This has a dampening effect on macroeconomic activity, such as private consumption and business investments. This is, of course, an undesirable consequence, but it is very likely not going to be substantial. Since the new exchange-rate policy will help bring inflation down, a new trend toward price stability will have a positive effect on the same categories of macroeconomic activity that will be adversely affected by somewhat higher interest rates.

Over time, as the economy returns to price stability both consumers and businesses will grow more confident about the future. This in itself is a booster for economic activity: the more predictable the future is, the more inclined we , as economic decision makers, to commit to higher levels of spending. We are also more inclined to make long-term decisions,in areas such as investing, home purchasing and changing jobs for new careers.

Since 2010, the Hungarian economy has benefited enormously from intelligent fiscal policies and structural reforms to both government spending and taxes. The Fidesz government has led the country from Europe’s economic backwaters to the very forefront, delivering solid economic growth, a rising standard of living and one of the lowest unemployment rates in the industrialized world.

The one price that the Hungarian economy has had to pay for this, is a level of monetary expansion that eventually became a catalyst for high inflation. This is a relatively small problem by international comparison, one that the central bank, the parliament, and the prime minister and his cabinet can easily address together. The necessary policy changes are not complicated, but rather tried-and-true textbook solutions.

Hungary is one of Europe’s major economic success stories. Bringing the current inflation episode to an end would only reinforce the country’s position as a role model for the rest of Europe.