Our history has known many economic crises. Some of them have spun out of control into disastrous episodes, with the Great Depression of the 1930s as the benchmark. As recently as in 2008-2010, Europe and America went through a bad economic downturn that ripped open wide gaps in many government budgets.

It also came with a major financial crisis, including but not limited to the meltdown of the Lehman Brothers investment bank. It was not the first bank crisis, not by a long shot, but it was of such proportions that one would expect that by now, we would have learned from it and taken all precautionary steps to prevent history from repeating itself.

Apparently, we have not. On Friday, March 10th, news stories erupted about how the Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) in California had imploded and fallen into so-called receivership with the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). The state government of California and the FDIC jointly took control of the SVB in a desperate attempt to save at least some of the money that customers had deposited with the bank.

How could this happen? After the crisis in 2008-2011, U.S. Congress passed a package of laws known colloquially as Dodd-Frank after its sponsors, Senator Chris Dodd and Congressman Barney Frank. The goal was to make sure no bank would ever run out of money again.

Which is exactly what happened to SVB.

The purpose of Dodd-Frank was to tighten regulations on the banking industry, and to intensify government oversight by means of new government agencies. A new legislative mandate, the so-called Volcker Rule, prohibited banks from investing speculatively for the benefit of the bank instead of its customers.

It remains to be seen if the Silicon Valley Bank broke any laws in its investment policies. To date, there are no indications that they did, which raises the question: with so much government oversight, and so many legal sideboards on their operations, how could this bank implode?

We are going to have to wait with a definitive answer to that question, but we can already draw one conclusion from this bank collapse. No matter how far government goes in regulating, supervising, and micro-managing the banking sector, it still cannot prevent a bank from going belly-up.

This is a conclusion with a lot of general value, but it is important specifically because at least one government agency is already introducing a new policy program in response to the SVB implosion. This program will potentially have far-reaching consequences for the U.S. economy, and therefore possibly for Europe as well.

Before we get to the details of that new policy program, it is worth noting that the SVB was not just any bank. With an estimated $220 billion in assets and $161 billion in deposits (according to various media sources), it was the 16th largest bank in America. A financial institution of that size does not implode overnight. A bank that ostensibly has $1.37 in assets for every $1 in deposits is supposed to have solid padding against crises.

Clearly, that was not the case with SVB. Regardless of how they got there, their crisis is being used by the Federal Reserve—America’s central bank—as an excuse to make a major course change in its monetary policy. This change, which copies a money-printing program from the European Central Bank, will allow the Federal Reserve to use the SVB crisis as an excuse to get back into its old habits of buying federal government debt.

This practice, also known as ‘quantitative easing’ or QE, was used by the Fed under President Bush and for part of Obama’s presidency. The practice was phased out when Janet Yellen chaired the Federal Reserve in 2014-2018, in part for fear that its excessive monetary expansion would eventually cause high inflation.

The Fed’s path back to QE is not straight and wide. It is almost as if they are keeping it in the shadows—for good reasons, of course. Currently, the Fed is engaged in a high-interest war on inflation (rightly so), the credibility of which would implode faster than SVB did, should the Fed’s plans for a policy shift become widely recognized.

So far, few seem to have connected the dots, which began showing up on Thursday, March 9th, when the SVB sold off a big pile of U.S. Treasury securities. According to the bank’s own Strategic Actions Mid-Quarter Update for the first quarter of this year, the bank sold $21 billion worth of sovereign debt. Interest rates had risen since they acquired that debt, resulting in a $1.8 billion loss for the bank (as prices and interest rates move in opposite directions).

When a seller puts that much supply onto the market in one day, there is a statistically clearly visible change in the market price. When supply increases radically, the price should drop and the interest rate rise.

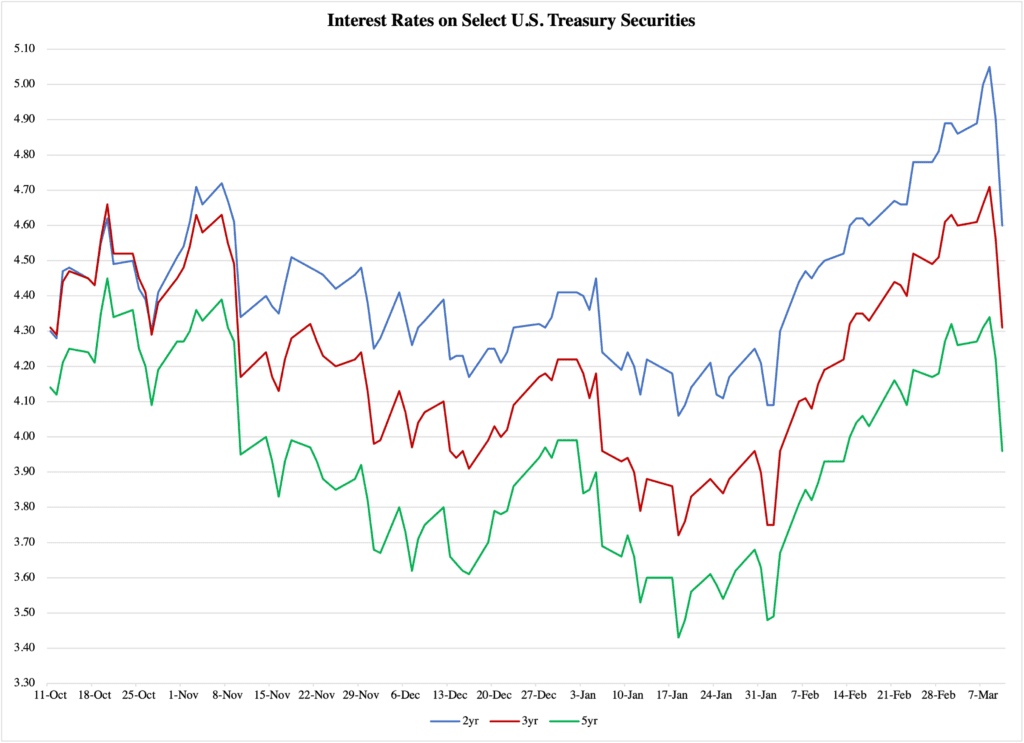

Surprisingly, as Figure 1 reports, the very opposite happened. According to the SVB’s Mid-Quarter Update, the average maturity of the bonds it sold was 3.6 years; Figure 1 reports the market interest rates on the 2-, 3-, and 5-year U.S. Treasury notes over the past five months. Notice the sharp drop right at the end of the period:

Figure 1

Source: United States Treasury

This drop in interest rates tells us that on the very same day that the Silicon Valley Bank dumped its $21 billion portfolio of government debt securities, the prices of those securities increased sharply. This market reaction is so uncharacteristic that it can only mean one thing: someone with very large resources was ready to step into the market and absorb the SVB’s portfolio.

Very few institutional investors in the market for government debt would have so much money available that they could turn a certain price plunge into a sharp price hike. The Federal Reserve is one of those institutions.

It would be unduly speculative to suggest that they actually entered the market in order to minimize SVB’s losses from their Treasury security fire sale. At the same time, it would also be naive to ignore the fact that the Fed would have two motives for doing so.

First, the Fed would want to prevent a sharp rise in interest rates. The central bank is already being criticized for its monetary tightening, which has raised U.S. interest rates over the past six months. Its currently tight monetary policy has pushed interest rates on some Treasury securities to 5%. As a result, Jerome Powell, the chairman of the Federal Reserve, was scolded by Democrat senator Elizabeth Warren when he recently testified before a Senate committee. Senator Warren accused Powell of destroying two million jobs in the U.S. economy.

Her argument was weak and inaccurate, ignoring the problem that all other alternatives to the current U.S. monetary policy are worse. However, of more importance is that Chairman Powell, while trying his best to defend the high-interest rate policy, is limited in how far he can push the current policies. The Fed is charged with combining two sometimes conflicting policy goals: maximum employment and price stability.

It looks like the Fed is quietly opening a path away from high interest rates and tight money supply, back to low interest rates and expansionary monetary policy. The first hint came in their Monetary Policy Report earlier this year when the central bank explained that they will have to push interest rates low again as a means to full employment. This is like asking for another inflation episode in the near future.

The Fed also has another motive for wanting to prevent an immediate spike in interest rates, as a result of the SVB collapse. If a bank fails and interest rates rise sharply, it can be interpreted by investors in government debt as a sign of a broader financial crisis unfolding—perhaps even a fiscal crisis. These events are often the result of self-fulfilling prophecies: financial investors are far more prone to acting on rumors than investors in any other sector of the economy. A sharp, anomalous rise in interest rates due to a bank collapse, could, so to speak, cause the very financial crisis that was not going to happen.

If indeed it was the Fed that intervened in the U.S. debt market late last week, and if they did it to prevent an economy-wide crisis, then they definitely did the right thing. However, on Sunday they took another step which suggests that any intervention earlier in the week would have had another motive.

On Sunday, March 12th, the Federal Reserve suddenly announced:

To support American businesses and households, the Federal Reserve Board on Sunday announced it will make available additional funding to eligible depository institutions to help assure banks have the ability to meet the needs of all their depositors … The additional funding will be made available through the creation of a new Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP), offering loans of up to one year in length

And now for the juicy part. The loans will be offered to

eligible depository institutions pledging U.S. Treasuries, agency debt and mortgage-backed securities, and other qualifying assets as collateral.

In plain English:

1. The Federal Reserve is going to lend money to American banks; and

2. The banks will guarantee the loans with holdings of U.S. government debt.

Officially, the Bank Term Funding Program is supposed to be a liquidity lifeline for banks, so that they do not have to sell their U.S. government debt at a loss in case they end up in liquidity trouble.

In reality, it is a thinly veiled way for the Federal Reserve to get back into the business of buying U.S. government debt.

The BTFP is a copy of the Term Refinancing Operations programs that the European Central Bank introduced in 2008. The aim of the TROs was to provide funds for European banks that purchased euro zone government debt.

In both cases, it works as follows. The central bank offers a commercial bank a loan worth, say, $1 billion. There are two conditions: the bank must hold government debt securities as collateral, and they must pay back the loan a year later. The bank either designates $1 billion of sovereign debt in its asset portfolio as security for the loan, or—and this is important—it buys $1 billion worth of government debt in the open market.

This is a profitable endeavor for the bank, which gets interest-rate payments on the debt securities it owns. At 4%, that means $40 million on a $1 billion portfolio. When the central-bank loan expires a year later, the bank is incentivized to hand over its government debt securities to its creditor. The reason is simple: the central bank values the collateral at par value—the best way to secure beforehand the asset transfer at the end of the loan.

Under the new BTFP program, the Federal Reserve is creating irresistible incentives for commercial banks to expand their holdings of U.S. debt. Since they are the ones buying the debt, officially it does not look like the Federal Reserve is simply printing money to monetize the U.S. government’s unending budget deficits. Yet just like with the ECB’s Term Refinancing Operations 14 years ago, that is exactly what the BTFP is going to do.

The collapse of the Silicon Valley Bank is proof that government, no matter how much it tries, can never prevent executives at a bank from running it into the ground. The reaction from the Federal Reserve is proof that government, in all its forms, is always, regardless of experience, willing to use a crisis to introduce new policies with unintended, yet potentially very bad, consequences.