The Swedish economy is in structurally bad shape, and without structural help, it will continue its glacial implosion. I have issued this warning repeatedly, in different formats: in 2022, in 2023, and in 2024.

Sadly, I am being proven right time and time again, especially in terms of the complete lack of productive policy response from the Swedish government. The most recent example is the budget proposal for 2026, presented on Monday, September 22nd, by Finance Minister Elisabeth Svantesson.

To her credit, the budget is good. It would have been an excellent platform for fiscal policy in Sweden—ten years ago. Given the shape that the Swedish economy is in today, Svantesson should have presented a completely different budget.

Before we get to the problems with this budget, let us give credit where credit is due. It is unusual, to say the least, to see a finance minister in Sweden, or in Europe generally, who is willing to think as an economist while designing fiscal policy. The incumbent center-right coalition government in Stockholm should get the credit they deserve for having stitched together a well-intended budget. It has all the right components to kick a sagging economy out of a recession and back into growth. Here are the highlights:

Again, good ideas—if the Swedish economy had been in a recession. But it is not in a recession. It is in a structural slump.

The most damning evidence that this is the wrong budget for the wrong economy is in the two temporary tax cuts. They would have been valuable components in an anti-recession package, but they are useless against the structural problems plaguing the Swedish economy.

If anything, the temporary tax cuts reveal a great deal about the economic reasoning among Svantesson and her economists at the finance ministry. These tax cuts are based on an erstwhile econometric mindset that is impervious to all sorts of more recent advancements in economic research.

To make a long story short: consumers can tell the difference between temporary and permanent changes to their household finances. They know that the VAT will go up again soon and will therefore use whatever increases in their cash margins that the VAT cut provides for increased savings.

They will most certainly not do what the Swedish government is hoping for, namely permanently increase their spending.

By the same token, the temporary cut in payroll taxes for young workers may, at best, result in a temporary increase in the hiring of young workers. At most, this increase will replace the hiring of workers older than 25—in other words, shift unemployment from young workers to the general workforce.

Furthermore, this temporary cut will very likely lead to layoffs of young workers once the cost of having them employed goes back to normal again.

The only piece in the list above that has some substantive merit to it is the work-requirement reform. I should caution that it, too, may be a temporary reform, but I have found no substantive reason to believe as much. Therefore, if we assume that it is actually meant to be permanent, it will lead to a permanent increase in labor supply.

Then again—no joy lasts forever—there is the problem with the Swedish economy not getting out of its slump. A stagnant economy has no need for an increased labor supply.

There is one last policy measure worth mentioning in this context, namely an ‘income tax cut’ in the form of an increased earned income tax credit, EITC. The Swedish version of the American EITC was introduced by the previous center-right government. It reduces the tax burden for low-income workers, thereby increasing the rewards for people who leave unemployment and join the tax-paying workforce.

As much as the Swedish EITC has lightened the tax burden somewhat on Swedish workers, it has also introduced the same distortionary effect on their tax system as our EITC did here in America. The EITC tapers off with rising income, thus increasing the actual tax faster than a person’s taxable income rises.

It is disingenuous to sell any kind of EITC as a genuine income tax cut when, in fact, it creates disincentives toward work. The marginal tax effect discourages lower-income workers from the type of workforce development that helps an economy grow over time. Bluntly speaking, the rapid rise of the income tax that an EITC imposes on a worker who pursues higher earnings actually traps lower-income workers in modestly paying jobs—and with that, in government dependency.

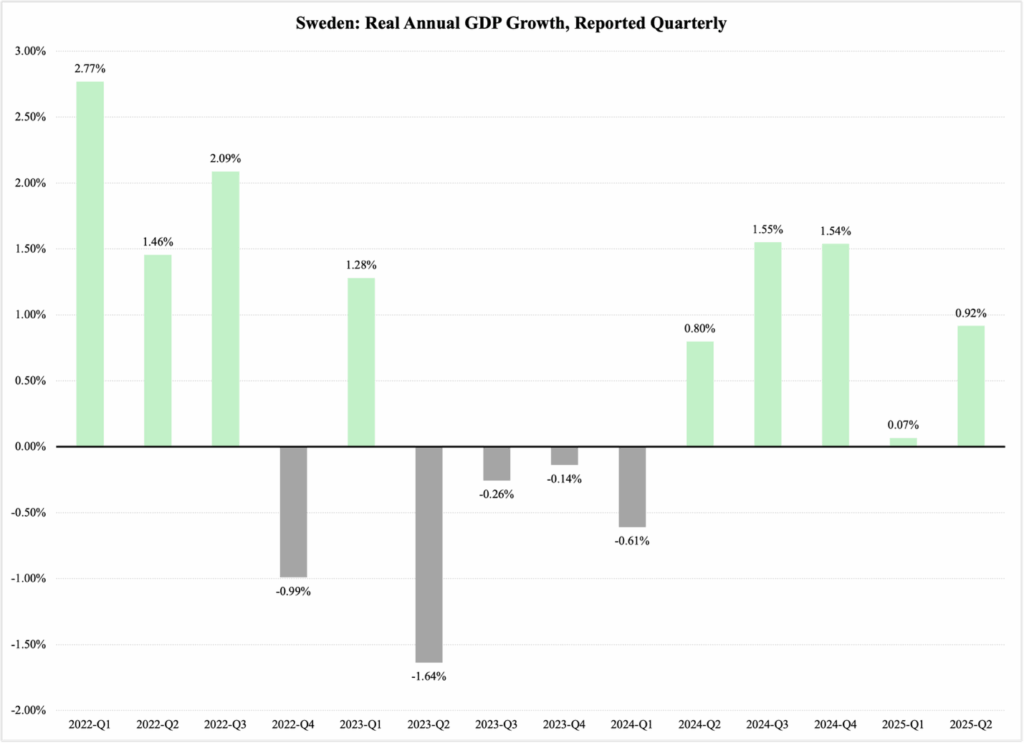

With all that said, the four reforms would have been good in an economy that was just about starting to climb out of a normal recession. But the Swedish economy is not in a normal recession. Figure 1 reports annual GDP growth rates since the first quarter of 2022:

Figure 1

The highest growth rate in the past 3.5 years is that of the first quarter of 2022, and that was ostensibly caused by a spillover effect from the pandemic rebound in 2021. Since Q3 of 2022, the Swedish economy has not even been able to reach 2% real annual growth but has instead suffered negative growth—a shrinking economy—for five quarters over a six-quarter period.

A recession is defined as two consecutive quarters with negative annual GDP growth. Even four quarters in a row, as in the Swedish case, is perfectly within the realm of macroeconomic normalcy. The problem with Sweden is that once their economy returned to growth in Q2 of 2024, the growth rates were so timid—1% on average—that it should have raised alarm bells in the Swedish public discourse.

Unfortunately, the Swedish government has grossly misinterpreted the non-existent recovery from the 2023 dip into negative growth. They still believe that it was a recession, and according to Svantesson’s presentation of the budget, the government believes that they are still in a recession. Their current forecast is that it will end in 2027.

Let me repeat: this is not the picture of a recession. It is the picture of a structural decline in economic activity. The perennially high unemployment rate—a seasonally adjusted 8.7% on average for the general workforce over the past year—grimly reinforces this picture.

It will take a completely different kind of policy package to get Sweden out of its structural slump.