There is a global move toward lower interest rates. The Euro-American hemisphere leads the way, and this is worrying. There is still a lot of extra liquidity in the European and North American economies—liquidity that was pushed out in the economies by central banks during the pandemic.

Put bluntly: there is a significant risk of a new inflation experience, one that is worse in every way imaginable.

When our central banks raised interest rates to curb inflation, they vacuumed up a lot of liquidity—commonly understood as money—that was just sloshing around in the economy. It was this excess liquidity that caused inflation, and it was the monetary tightening that returned us to at least a semblance of price normality.

Unfortunately, the world’s central banks seem to have lost their memories. The point where they are cutting interest rates is far too close to the ‘base’ of the inflation episode we just went through.

Let me explain this in more detail in just a moment. First, a few examples of the trend of lower interest rates. Here are some interest-rate moves so far this year by first-tier European and American central banks:

Some second-tier central banks have also reduced their interest rates:

Not all central banks in Europe follow the trend. The National Bank of Serbia decided recently to maintain its policy rate at 5.75%. However, it is an exception to the overwhelming trend of lower interest rates—and expanding monetary supply.

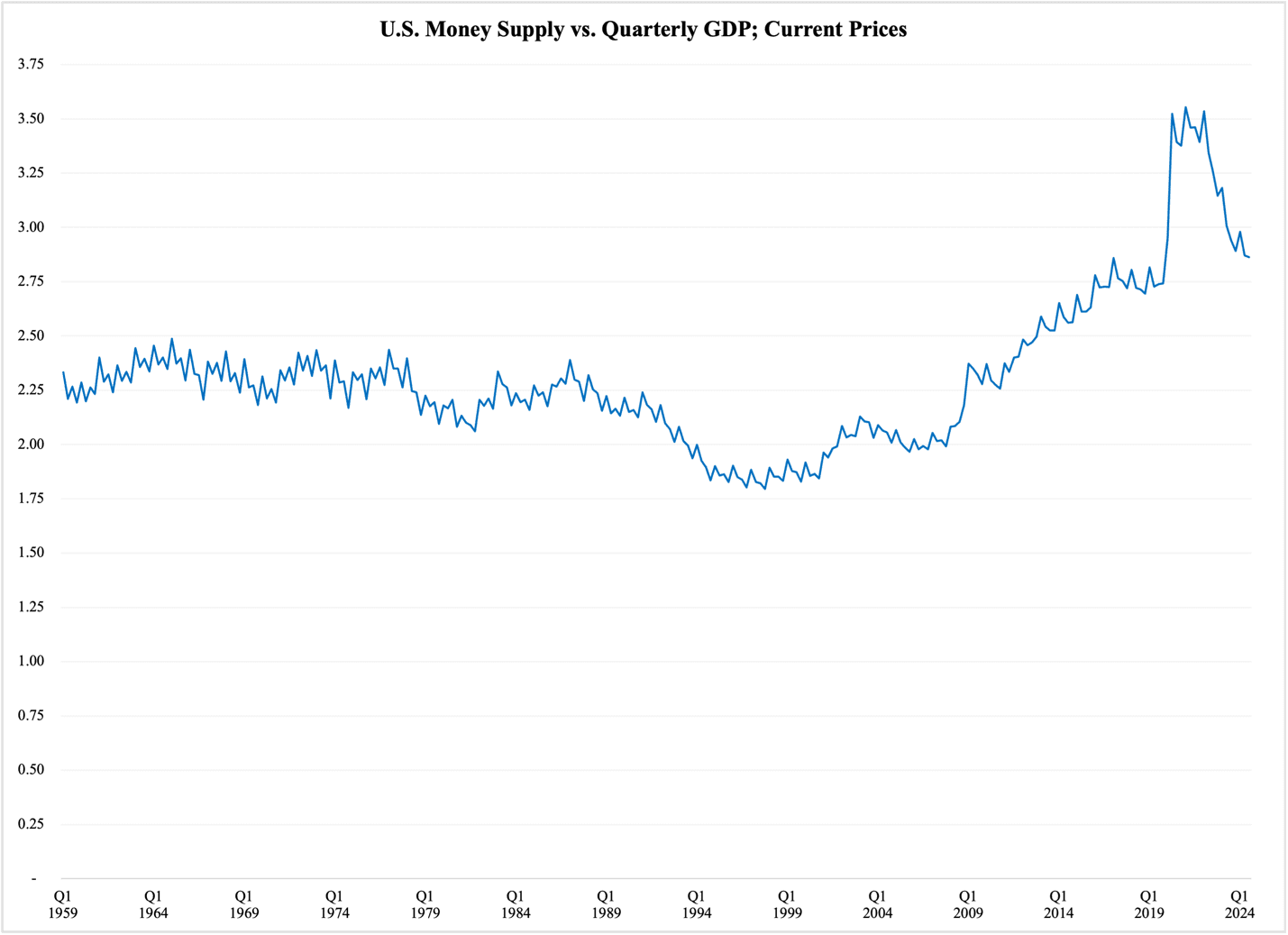

As I recently explained, the Federal Reserve is a case in point here. Figure 1 reports the velocity of money in the U.S. economy, i.e., the stock of money supply (under the M2 definition, for all you monetary nerds out there) divided by quarterly current-price GDP.* It is glaringly evident that monetary expansionism is a new phenomenon, with money supply outpacing GDP only in roughly the past 20 years:

Figure 1

The relevant portion of Figure 1 is the peak in 2020-2022. This was the exorbitant money printing that caused inflation rates not seen in 40 years.

That part was bad enough, but the really scary part is at what money-to-GDP levels we see now when we leave that peak behind. In other words,

Let us remember that the inflation that we recently experienced was the result of the money supply rising from $2.75 per $1 GDP. We did not see a rise in inflation when the money-to-GDP ratio increased from $2.00 in 2009 to $2.75 in 2019.

In other words, now that the Fed stops reducing its money supply— i.e., starts cutting interest rates—it leaves us no margin in the money-to-GDP ratio for any policy mistakes. The risk of a new monetary inflation episode is overwhelming. If the Fed had allowed the money supply to contract to levels we saw 15 years ago, the U.S. economy would have been a lot safer from new eruptions of monetary inflation.

Again, the analysis of the U.S. money-to-GDP ratio applies to many other countries as well. Every economy that first saw a rapid monetary expansion followed by high inflation, and then a sharp monetary contraction that ended inflation, is vulnerable to a similar experience.

But would our central banks really be stupid enough to print money again and thereby cause another monetary episode? If left alone to go about their business, the central banks probably would not do this. However, it is far from certain that they will be left alone in the coming years, and the reason is spelled budget deficits.

For reasons I will return to, I am acutely worried that the deeply indebted governments in Europe’s welfare states, as well as the federal government in America, will once again resort to deficit monetization as a means to borrow money. If they do, as I explain in this article, co-authored with fellow economist Robert Gmeiner, it is a practical certainty that inflation will return—only this time, it will be much harder to control.

* When turned the other way around, so that GDP is divided by money, this ratio is known as the velocity of money. As used here, with money divided by GDP, the ratio is more geared toward answering questions about the inflationary effects of monetary expansion.