Last week brought some good news for the European economy when the ECB decided to keep its policy-setting interest rates unchanged.

In accordance with my forecast six months ago, the Federal Reserve did the same. Back in early May, I predicted that with its federal funds rate in the vicinity of 5%, the Fed would not make more than one or two rate hikes for the remainder of the year.

That is exactly what has happened. On November 1st, the Federal Open Market Committee, FOMC, decided “to maintain the target range for the federal funds rate at 5-1/4 to 5-1.2 percent.” The FOMC explained that it is still more likely to raise interest rates than to lower them:

In determining the extent of additional policy firming that may be appropriate to return inflation to 2 percent over time, the Committee will take into account the cumulative tightening of monetary policy, the lags with which monetary policy affects economic activity and inflation, and economic and financial developments.

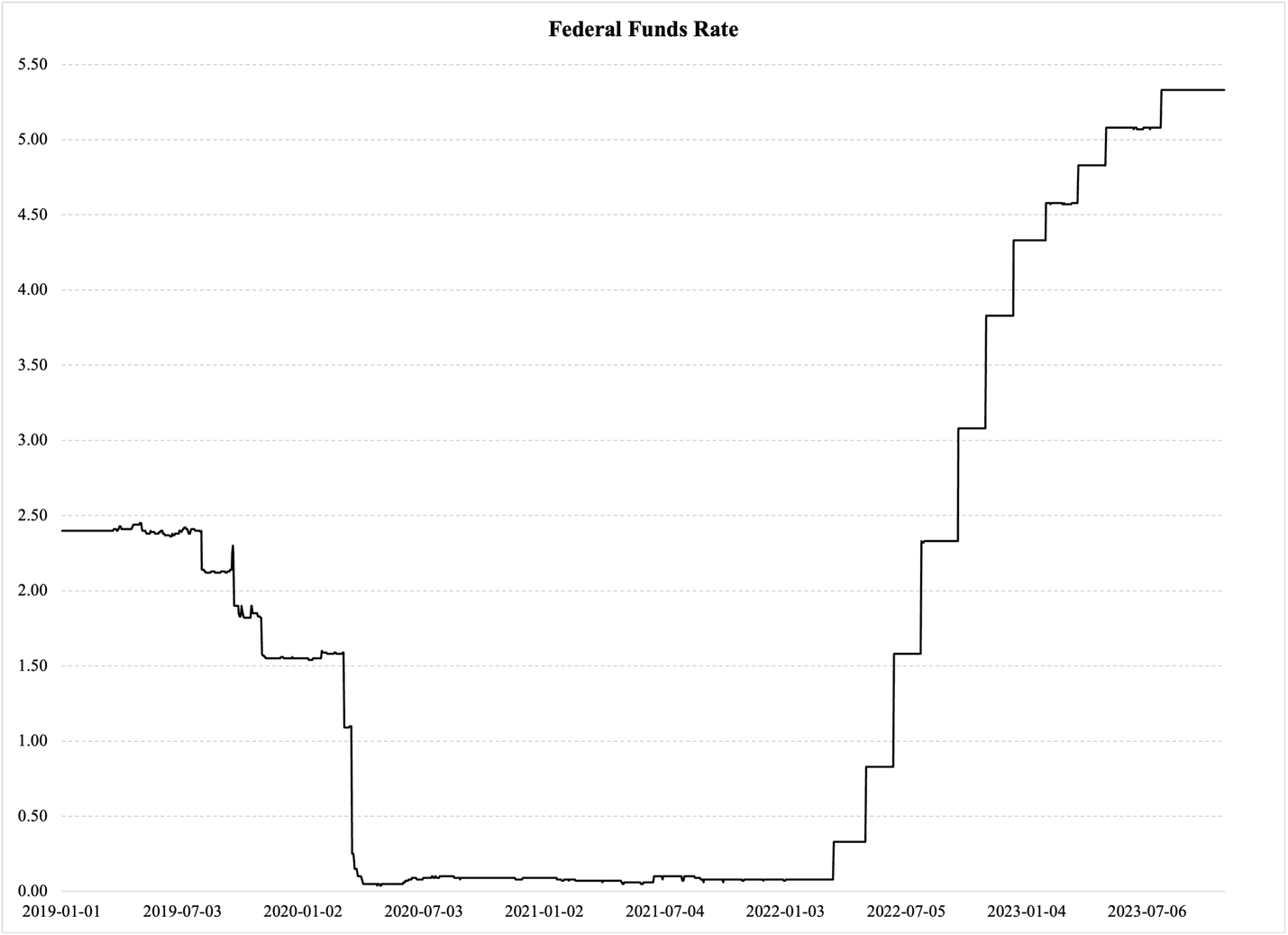

It would take a crisis to motivate the FOMC to raise interest rates between now and the end of the year. As Figure 1 reports, there was indeed a break in the trend of rising rates earlier this year. It significantly slowed down the pace at which rates were rising. It was the second sharp turn in policy since the 2020 pandemic, with the first obviously being the start of the rate hikes:

Figure 1

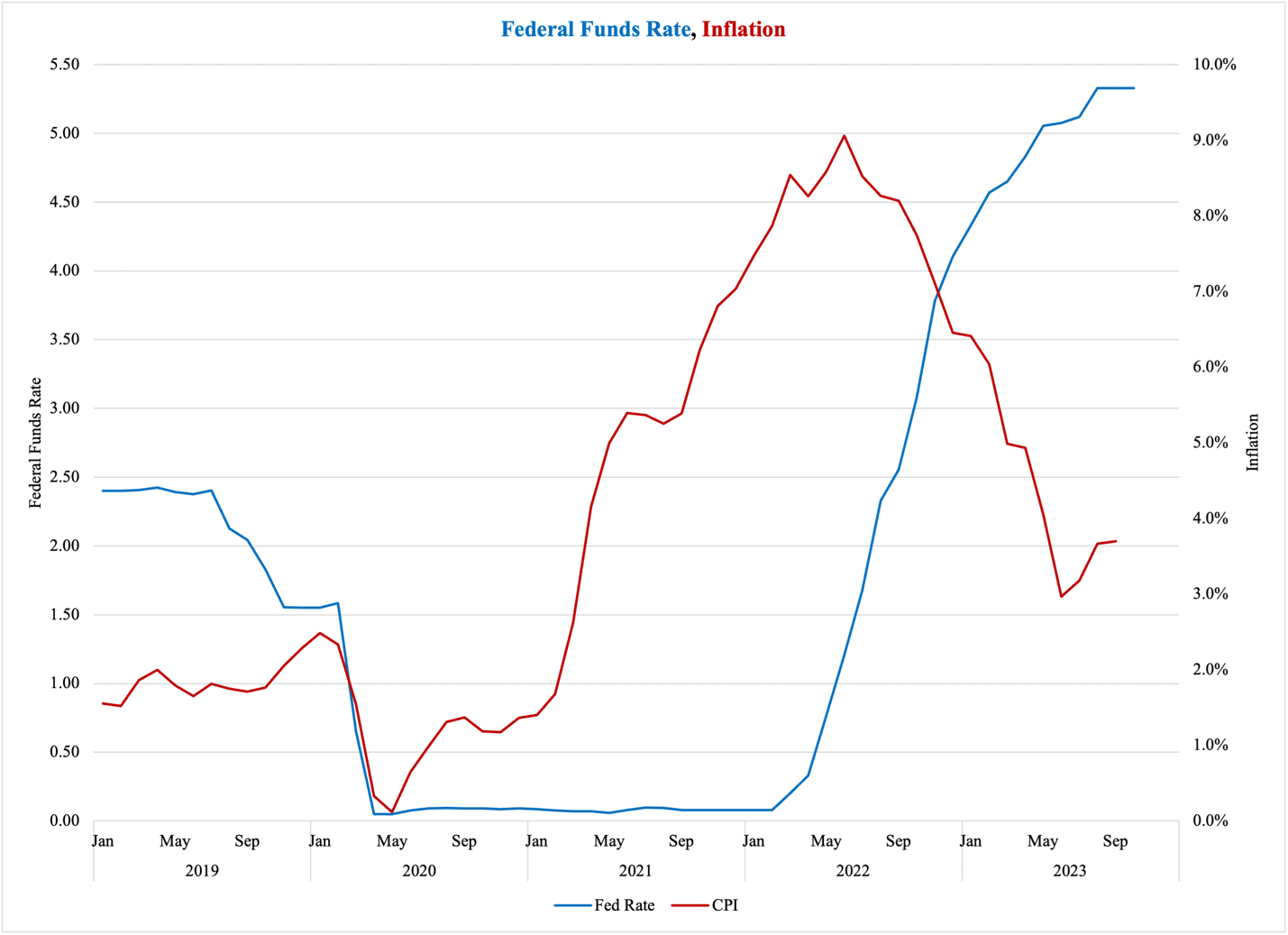

The goal of these rate hikes has, of course, been to bring inflation down again. To see just how effective this monetary tightening has been—and how the Fed’s own monetary expansion in 2020 caused inflation—let us plot the monthly averages for the funds rate together with U.S. inflation (represented by the Consumer Price Index):

Figure 2

The money-printing episode that took place during the pandemic is visible in both Figure 1 and Figure 2 as the sharp dive in the federal funds rate in early 2020. Inflation, which was approximately 2% in 2019, temporarily fell to virtually zero as the U.S. economy artificially shut down. Then, by early 2021, prices started rising sharply: just as Robert Gmeiner and I explained in our article in the American Business Review, the money printing of 2020 set off an inflation bonfire in the economy.

In early 2022, the Federal Reserve began its year-long monetary tightening. Consequently, inflation contracted and fell from its 9% peak in June last year to its current level in the 3.5-4% range.

Looking at Figure 2, it would make sense for the Fed to continue to raise its interest rate until inflation fell to the 2% level that the central bank has set as its goal. However, it is important to take the rest of the economy into account here. Monetary inflation has for the most part been eliminated; what is left now is predominantly a case of traditional demand-pull inflation, in other words, the type of inflation that characterizes a strong economy.

As I recently pointed out, the U.S. economy is strong and shows no signs of a recession, which means that it is only natural to expect a certain level of traditional excess-demand, or demand-pull, inflation. The problem for the Federal Reserve is that this type of inflation should not be much higher than 3% when the economy is as strong as it is today. The fact that we are seeing stubborn inflation rates closer to 4% than 3% suggests that the third type of inflation is at work here. Thanks to a strong labor market and to workers attempting to compensate themselves for inflation, the U.S. economy is currently experiencing a dollop of cost-push inflation on top of demand-pull inflation.

Again, monetary inflation is no longer the main problem.

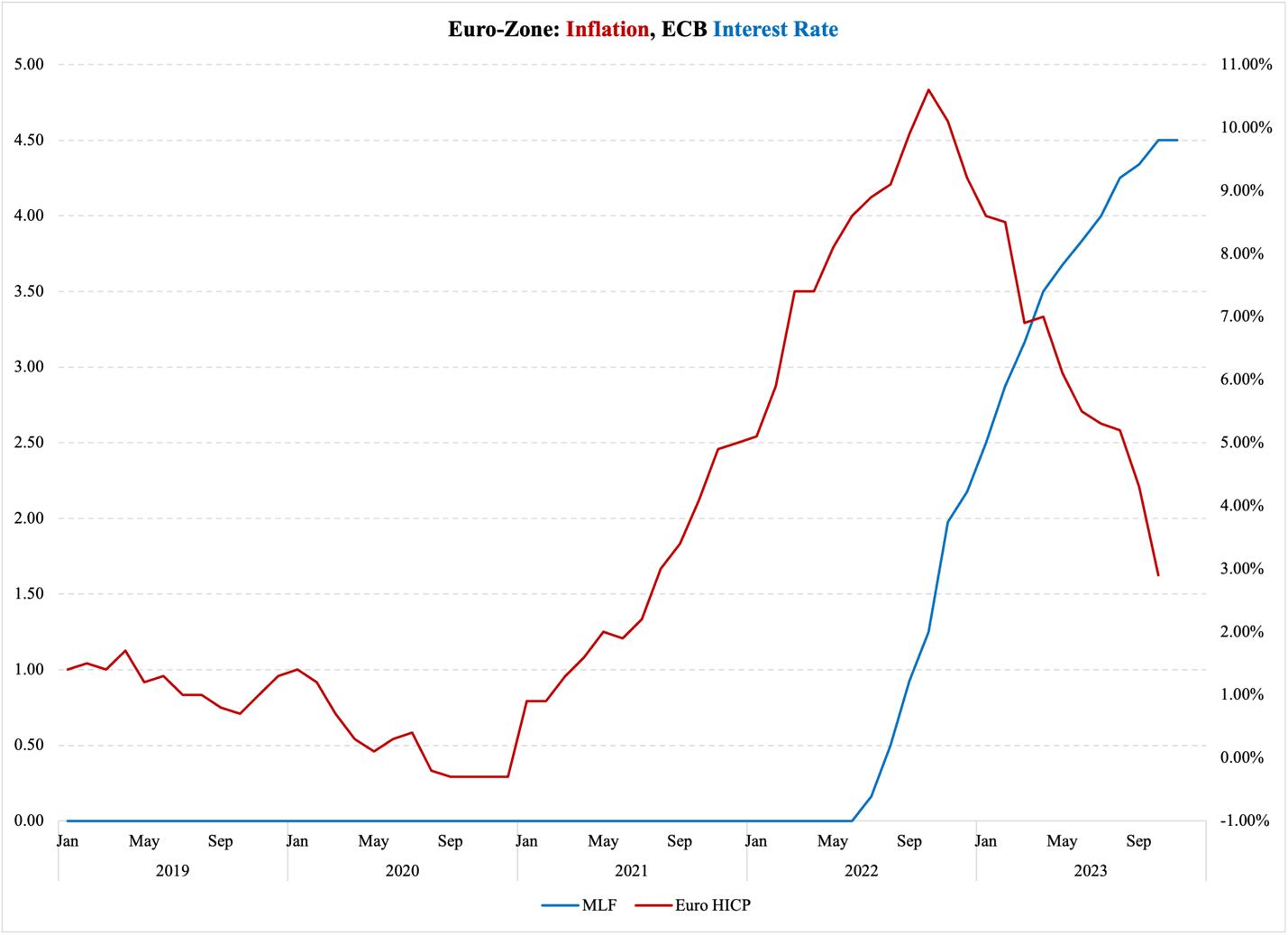

Europe has followed in America’s footsteps and rooted out monetary inflation with tighter money supply. As Figure 3 shows, the European Central Bank has raised its governing interest rates almost exactly along the same path as the Federal Reserve has—the only difference is that the ECB got started almost half a year after the Fed did. As Figure 3 shows, as soon as the monetary tightening begins, euro-zone inflation turns downward; the ECB’s three policy rates are represented by the marginal lending facility, MLF:

Figure 3

The ECB’s decision not to raise interest rates further, which preceded the Fed’s decision by six days, seems counter-intuitive given their success in bringing inflation down. If fighting inflation was their main goal today, the ECB’s Governing Council—its policy-making board—would certainly have added another quarter of a percent to the current rates. However, in their October 26th statement they hint at other concerns:

The Governing Council’s past interest rate increases continue to be transmitted forcefully into financing conditions. This is increasingly dampening demand and thereby helps push down inflation.

Unlike the U.S. economy where demand-pull inflation is making itself known, the European economy is weak and lacks underlying strength. Eurostat still has not published any estimate of the euro zone economy in the third quarter, but as I have pointed out once a week now for at least a month, Europe is on its way into a recession. The ECB, with its well-staffed research departments, is no less aware of this than I am. To avoid aggravating the economic downturn, they decided to keep interest rates unchanged for now.

In other words, there are different motives behind the Fed’s and the ECB’s monetary policy decisions. On the American side, the monetary tightening has done its job and the economy is largely returning to normalcy; in the euro zone, there is still monetary inflation to be rooted out, but the macroeconomic side effects of further ECB tightening would outweigh its benefits.

Cynically speaking, by sliding into a recession the euro zone economy will do the job for the central bank: it will root out the remainder of its monetary inflation simply by freezing macroeconomic activity. This is, of course, an exaggeration of the causal chain, but the point is salient: if the ECB kept raising interest rates when the economy is in a downslope, it could easily escalate a recession into a depression.

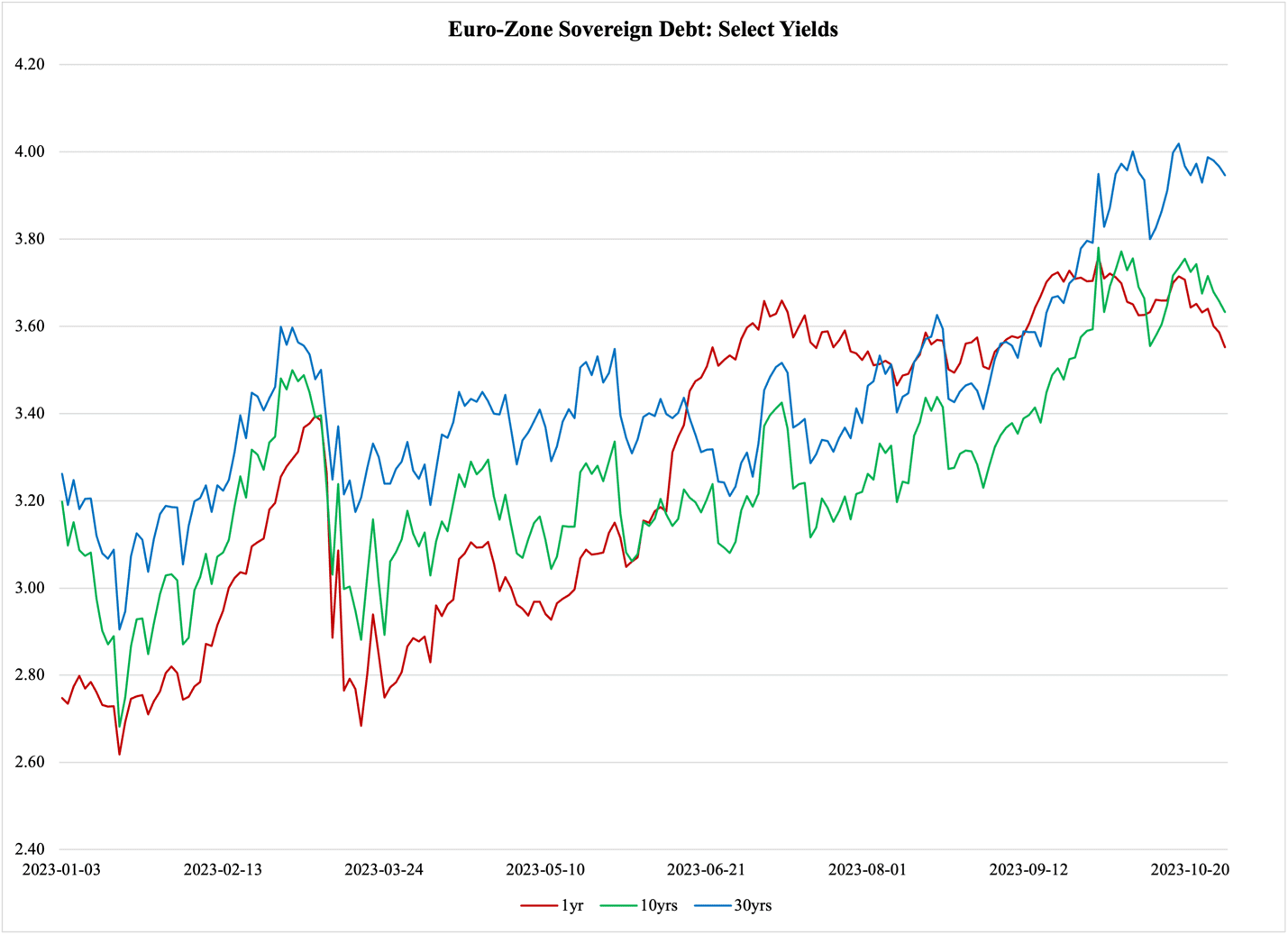

Judging by reactions in the market for euro-denominated sovereign debt, the ECB gained confidence from investors with its decision not to raise interest rates further. As Figure 4 explains, yields on treasury securities actually tipped downward after their October 26th meeting. All other things equal, this would be the start of a downward trend that could bring some credit-cost relief, just in time for the recession:

Figure 4

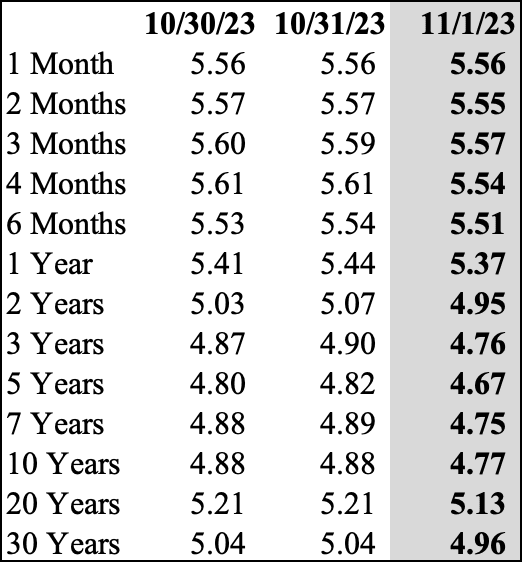

The market for U.S. debt saw a similar reaction upon the Fed’s decision to leave the funds rate unchanged. Interest rates fell on almost all maturities. In Table 1 below, the gray column marks the yields in the market for U.S. debt at the end of trade on Wednesday, November 1st, the day when the Fed held its meeting:

Table 1

Rates fell on almost all maturities, but the substantial decline happened in the longer end. The drop of 14-17 points on maturities in the 2-7-year spectrum is not unheard of, but definitely unusual. This is a sign of big money flowing into the debt market to buy up longer-term government debt.

Just as the rate drops in Europe signaled investor confidence, so these sharp yield drops could be a way for investors to reward the Fed for its policy. If rates had dropped on short-term but not long-term debt, as has happened in the past, it would have been an expression of the opposite market sentiment. Investors would have signaled that they were at best willing to park their money in U.S. government debt for a few weeks or months.

We must not draw too far-reaching conclusions from these market movements. Just like stock markets, the markets for sovereign debt are fluid and have a tendency toward volatility. That said, whenever there are sharp yield swings, they usually happen because of uncharacteristic interventions by the central bank, or because investors have reasons to believe that the government whose debt they are investing in could face credit problems in the near future.

This last point is essential to keep in mind here. While there is calm and some signs of confidence in the markets for government debt under both the U.S. dollar and the euro, we must not forget that just because the two central banks have chosen to keep their interest rates unchanged, the fiscal outlook for the indebted governments looks the same.

If anything, the fiscal outlook could worsen in the coming months. With Europe going into a recession, it would be almost a miracle if any one government in the euro zone did not experience budget deficits in 2024. Many of the 20 euro-zone members have just emerged from the fiscal shock that came with the artificial economic shutdown during the 2020 pandemic; if their government finances return to red ink this winter, it could spell trouble for them in short order. The debt market would drive up interest rates, forcing the ECB into a policy dilemma that I have pointed to several times in the past:

This is not a situation the ECB wants to find itself in. Unfortunately, its contribution to alleviating the coming recession is already on the table; it has no more arrows in its quiver. The ball is now in the legislative court: it is time for the European Parliament and member states to consider what they can do to stave off a recession. The end of this article gives some ideas of what they can do.

Things are a little bit better on the American side, given the underlying strength of the U.S. economy. So long as GDP growth generally stays where it is now, tax revenue will continue to pour in and replenish government coffers. The federal budget deficit will not go away, but in the short run—over the next six months—this moderates the risk of a fiscal crisis.

For the longer term, though, the U.S. government remains in the danger zone for a vote of no confidence from sovereign debt investors. Spending remains on its usual, unsustainable track, while Congress does nothing of substance to put an end to the trillion-dollar deficits. The new House Speaker, Mike Johnson, has declared a bold ambition to bring federal spending under control, but his only substantive idea is to do what Congress already did 13 years ago: to appoint a bipartisan debt commission.

That commission made no difference to the federal government’s indebtedness. Nothing suggests that a new debt commission would be any more successful.

With only two months left to go of this year, the two big central banks flanking the North Atlantic have struck a note of confidence with their debt-market investors. Let us hope that this is the beginning of a better outlook for Europe and that America’s fiscal policymakers seize a rare opportunity to make a permanent difference for the better.