With just over a year to go to the 2024 U.S. presidential election, a growing number of opinion polls tell us which candidate is ahead, and what issues voters are most concerned about. Unsurprisingly, the economy has risen to the top spot: over the past two years, families across America have felt the inflation squeeze on their paychecks.

The inflation episode overlaps with Joe Biden’s presidency. Voters who reminisce about growing wages, plenty of jobs, and price stability under President Trump are much more likely to trust Trump’s party with handling the economy: 49% prefer the Republicans on that issue, while only 28% favor the Democrats.

With an impressive margin, voters also rank the economy as the most important issue for them. In a recent Statista survey, a total of 34% put the economy, jobs, and inflation at the top of their list. If we add those who ranked “taxes and government spending” highest, 40% of the voters belong in the economy-first category. This puts the economy almost 30 percentage points ahead of any other issue.

Given the attention that voters pay to the economy, the media is quick to report on economic news. Every time a statistical agency releases new numbers on GDP, inflation, jobs, or any other major economic variable, a flood of news stories and commentaries aspire to make sense of what it means, and where the economy is heading.

The good side of this is that people with an understanding of economics bring complex issues down to a level where the proverbial ‘Average Joe’ can make sense of it. The bad side is that analysis and commentary on the economy also attract a great deal of political punditry. Economic information that can easily be presented in an unbiased fashion is obscured by those who want to spin the news to their political liking.

A case in point is the latest so-called jobs report—a monthly update from the Bureau of Labor Statistics on the U.S. labor market. The latest one, which came in early October and reported on employment and unemployment in September, inspired particularly disparate comments, depending on the political leaning of the commentator.

On the Left side, they went to great lengths to portray the jobs report as positive news on the economy. On October 6th, Jeff Cox over at CNBC explained that the September jobs report was “stronger than expected.” He referred to it as “a sign that the U.S. economy is hanging tough.” An even more laudatory comment was published over at CNN.

A somewhat more moderate position came from the economic news site Morningstar. In an in-house interview with their own chief economist Preston Caldwell, Ivanna Hampton suggested that the report was so strong that it “plowed through Wall Street’s expectations.” Forecasters had predicted half as many jobs being created as the economy actually churned out. Caldwell, in turn, offered no discernible comment on the jobs report, other than that there may be a recession coming.

On the Right side, critical to the BLS jobs report, economist Vance Ginn stands out. Back in September, Ginn explained that the BLS jobs report for August pointed to “a weak labor market.” Writing on the September report, he painted with equally negative colors. The U.S. economy, he concluded, is weak and facing “major challenges.”

So what is the truth? Is the performance of the economy really in the eyes of the beholder?

No, it is not. We can reach a firm conclusion about how the U.S. economy is doing, based on indisputable facts and dispassionate analysis. We can do so either by arguing the case against pundits on both sides of the aisle, or we can pursue an informed conclusion by simply laying out the case and letting it speak for itself. While it is tempting to do the former for pedagogical reasons, it is a time-consuming exercise that leaves only scant room for an assessment of the U.S. economy itself. Hence, we take the latter approach.

Needless to say, an analysis of the economy spans a lot more than the labor market. Part II of this article will delve into the latest numbers for gross domestic product, GDP. For now, though, we focus on jobs, unemployment, and related variables.

When we discuss the labor market and its performance, the central piece of information is the pace at which private-sector employment is growing. The rate of jobs growth in businesses and other parts of the private sector is preferable to the rate which includes government:

Since the private sector produces value and government does not, the jobs growth in the private sector is a critical measure of economic performance for the entire economy.

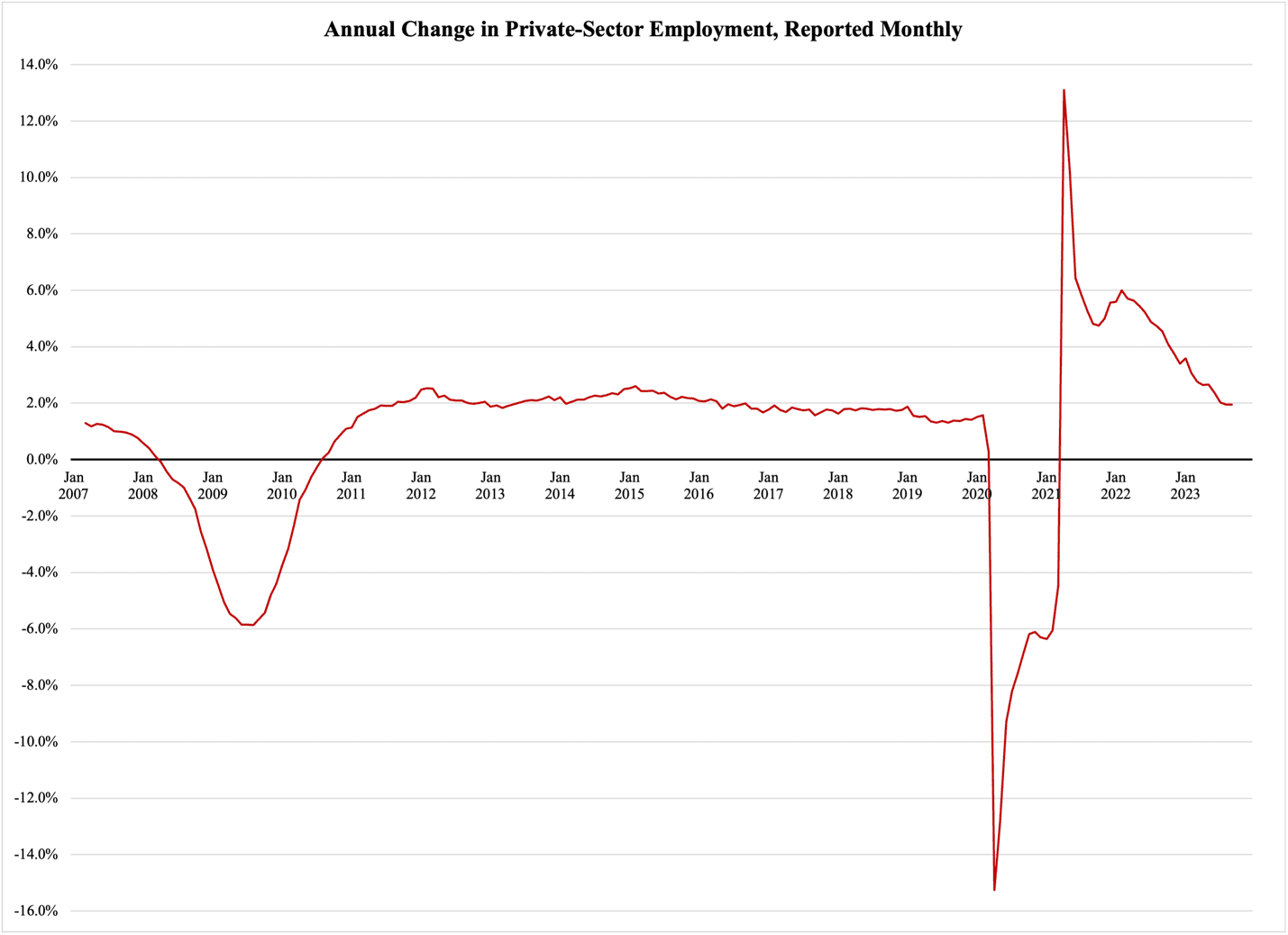

Figure 1 reports the annual rate of change in private-sector employment in the U.S. economy. Right after 2007, there is a decline in employment due to the so-called Great Recession in 2008-2009. It is followed by a recovery in 2010. For the remainder of the ’10s, the private sector adds new jobs at a pace of 2% per year, or marginally higher.

Figure 1

The 2% annual growth rate is so stable that we can safely refer to it as a long-term trajectory for the labor market. Such trends are usually misinterpreted by economists as evidence of ‘general equilibrium,’ a methodological error that leads to hasty conclusions about the economy. We shall refrain from going down that aisle; all we need this trend for is a comparison to more recent events in the labor market.

When the artificial economic shutdown happened in 2020, the stable trend in jobs growth was violently disrupted. After very large swings downward and upward in the labor market, we see a lingering effect of higher-than-normal jobs growth into 2022 and the first half of 2023.

It is not until June that the rate, at 2.36%, falls in the proximity of its long-term trend. Since then, it has averaged 1.97% in yearly growth of employment.

Given the stable trend of employment growth in the past decade, the simplest interpretation of the most recent jobs numbers is that the economy now definitely is back on a long-term trajectory of economic expansion. Other labor-market variables corroborate this conclusion but with a slight bias toward a weaker-than-trend future for the economy.

Unemployment is another indicator of labor market performance. In September, 3.6% of the workforce was unemployed. This is an improvement over 3.8% in June and July, and 3.9% in August. It is easy to see this as a sign of economic strength, but the jobless rate always increases in the summer when working-age school kids and college students are not in class.

Of more importance is the fact that the September jobless rate was a modest but statistically visible uptick over last year’s September figure of 3.3%.

Is this a sign of weakness in the U.S. economy? No, it is not. The August number of 3.9% was also higher than the same month in 2022, but only by a tenth of a percent. To get an idea of where the economy is heading, we need to look at other labor-market variables.

Another popular number is the workforce participation rate, i.e., the number of working-age people who have a job, plus the people who would like a job but don’t have one, i.e., the unemployed. In September, the U.S. workforce participation rate was 62.7%, which is an increase from 62.2% in the same month last year. Workforce participation is consistently higher this year than in 2022, and in the past four months, it has been 0.4-0.5 percentage points higher.

As I explained recently, this rise in workforce participation is enough to explain any signal of a recession that may come from the unemployment numbers. The rise in workforce participation is a symptom of the inordinately high immigration that has taken place under the Biden administration. This grows the workforce age population, but if the immigration has a slant toward work-seeking individuals, it explains the rise in workforce participation.

So long as unemployment and workforce participation are on the rise together, we cannot speak of a recession warning for the economy. The statistical combination to watch for is an increase in unemployment coupled with a decrease in workforce participation.

Weekly paychecks can tell us a great deal about the job market. This year’s September figure was 3.5% higher than in September 2022: the average employee in the private sector earned $1,160 this year; last year’s number was $1,121. This paycheck increase is due entirely to a higher average hourly wage of $33.82, up 4.1% from $32.48 in September last year.

Under normal circumstances, a rise this big in average weekly earnings would be a sign of a strong economy. That is not the case here, and the reason is, not surprisingly, inflation. Based on the CPI, or Consumer Price Index, published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. inflation topped out at 9.06% in June last year; when measured using the PCE, or Personal Consumption Expenditure, index, the inflation high point was 7.1% (using 2017 as index year).

Regardless of which method we use, it took a year for inflation to come down to levels close to normalcy again. Concentrating on PCE, its inflation rate dropped to 3.2% in June.

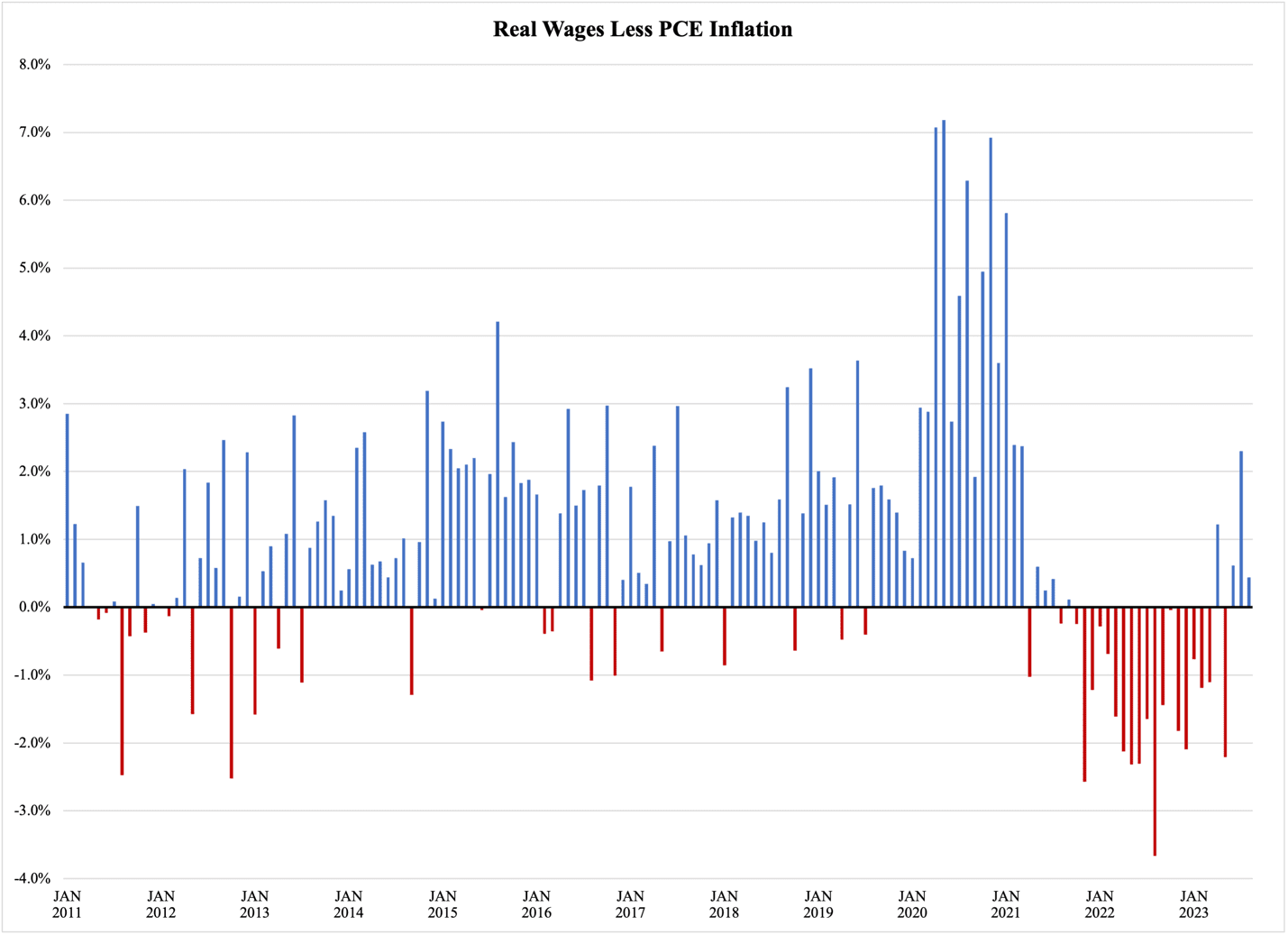

Figure 2 reports the growth in real wages, with the money from the aforementioned BLS data and inflation per the PCE method. Blue columns mark months where the yearly increase in money wages has exceeded price increases; red columns mark months where inflation was higher than the growth rate of the money wage:

Figure 2

The cluster of red columns, marking a decline in real wages, toward the end of the horizontal axis in Figure 2 is consistent with the high-inflation episode that followed the 2020 pandemic.

It is well-known that real wages fell during the high inflation episode. What is less well known is that they rose significantly during the pandemic. From January 2020 to January 2021, the average weekly wage in the U.S. economy increased by 7.4%. This is the highest January-to-January increase since at least 2008.

Over the same period of time, inflation was 1.6%.

To see the net gain over these two periods of time, we compare a $100 paycheck in August 2019 to the same month every year since then:

In other words, in 2023, workers were 2.6% ahead of 2019 in terms of their real wages. This is a very small gain for a four-year period, but it is still a gain. It suggests that inflation, while battering the economy as hard as it did, has not left any lasting scars.

With the growth in private-sector jobs apparently returning to its long-term 2% growth trajectory, it looks like the U.S. economy is ho-humming along relatively unscathed. However, we will know more about that when we examine the latest GDP numbers in Part II next week.