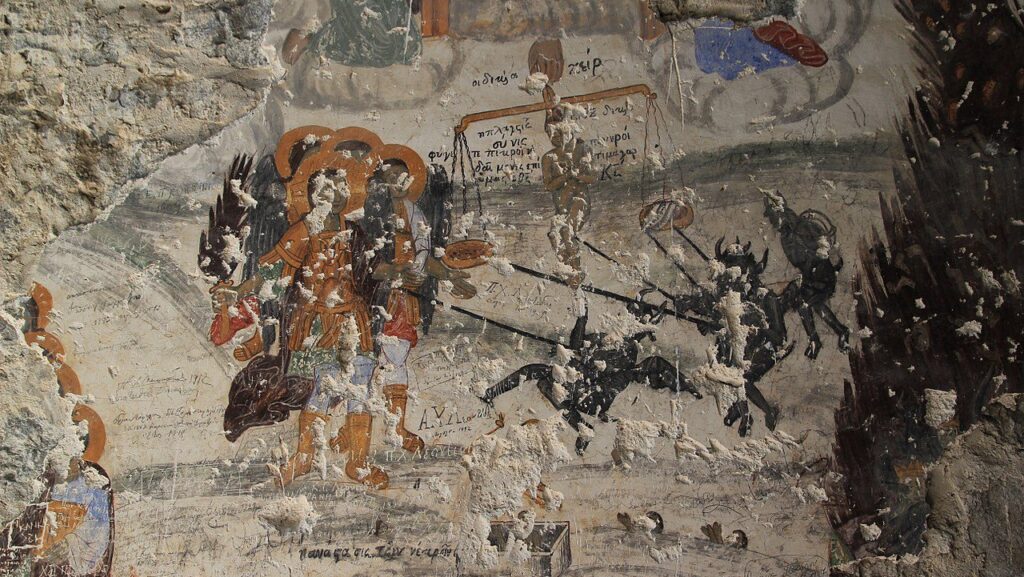

Representation of the Last Judgment in the Vazelon Monastery

The Turkish government, as well as the Turkish nationalist opposition, have recently prevented an Orthodox liturgy from occurring on its traditional date at a historic monastery, Sumela, in the city of Trabzon. After discovering that the city was conquered by Ottoman Turks on August 15 (a Christian Holy Day observing the ’Dormition of the Mother of God’) in the year 1461, the Turkish government absurdly decided to impose a change to the Orthodox Christian calendar in Turkey. They advocated that, instead of August 15, the observance of the religious ceremony should take place on August 23, purely for Turkish convenience.

The worship, previously set for August 15, was thus postponed to the following week by the governor’s office of Trabzon since it coincided with the anniversary of the Ottoman conquest of Trabzon. The Dormition of the Mother of God is a High Feast Day of the Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, and Eastern Catholic Churches. It celebrates the ’falling asleep’ of Mary the Theotokos (’Mother of God,’ literally translated as ’God-bearer’), and her ascension into heaven.

The Association of Turkish Travel Agencies announced that the liturgy would be accessible only to accredited guests who are approved by the governor’s office. After the ceremony, the site was reopened to tourists. Parallel to changing the day of the liturgy for Orthodox Christian believers, Turkish nationalist groups also pressured and threatened Christians. Consequently, they significantly reduced the number of liturgy participants. Maria Zacharaki, a journalist based in Constantinople, reported on the liturgy:

The divine service is held in an atmosphere of intense vigilance due to fear of protests from nationalist circles although the local police have taken all necessary measures to preserve order.

Instead of the usual crowd of more than 1000 people gathered every year for the divine service on the fifteenth of August, this year only 50 believers from Greece and Georgia participated in the ceremony, casting a heavy shadow on this religious event.

The security measures were particularly strict, with the Turkish authorities blocking the passage of vehicles to the monastery from 08.00 in the morning, while only visitors with special permission were allowed to attend.

The city of Trabzon was founded by the Greeks in the 8th century B.C. It is located in the historic region of Pontus. The Sumela Monastery was also established by Greeks around A.D. 386, during the reign of Roman Emperor Theodosius I (r.375-395), by two monks from Athens named Barnabas and Sophronios. Sumela thrived for centuries within Greek Orthodoxy as a prominent center for learning, worship, and artistic production.

Pontus, an ancient Greek word for sea, refers to the Black Sea and surrounding coastal areas. The presence of Greeks on the shores of the Black Sea began millennia ago. The Greek cities founded on the Anatolian shores of Pontus, beginning in the 8th century B.C., included Sinope (Sinop), Amisus (Samsun), and Trebizond (Trabzon or Trapezus), among others. Pontus was the birthplace of great thinkers such as the philosopher Diogenes of Sinope and the geographer Strabo of Amasia. Today, these are important Turkish cities. In fact, most cities in Turkey were founded by Greeks.

Byzantium, for instance, was established by Greeks from the city of Megara (near Athens) with their leader, Byzas, in 667 B.C. This city was later renamed Constantinople (now Istanbul), which became the capital of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire in A.D. 330. Trebizond was also a part of the Roman and Byzantine Empires. The Asia Minor and Pontos Hellenic Research Center notes:

In 313 A.D., Roman Emperor Constantine granted Christians religious freedom … The emergence of Christianity as the official religion of Rome led to the creation of great monasteries that served as centers of Christian and Hellenic (Greek) learning, along with universities and schools. A number of saints, patriarchs, and bishops of the Orthodox Church were from the Pontus region.

In 1204, the Greek Empire of Trebizond was established in the Pontus region. Ottoman Turks invaded Constantinople in 1453, bringing an end to the Eastern Roman/Byzantine Empire. In 1461, the Ottoman Turks invaded Trebizond. It was the last independent Greek state until the modern nation of Greece was established in the 19th century. According to the Asia Minor and Pontos Hellenic Research Center,

After the fall of Trebizond, Pontian Greeks suffered large-scale massacres and deportations. During the 17th and 18th centuries, approximately 250,000 Pontian Greeks were forced to convert to Islam. Thousands retreated inland or fled the area for Russia, Constantinople, and the Danubian Principalities (modern day Romania).

The 19th century fostered a renaissance in Pontian Greek society, which numbered approximately 700,000 people. More than 1,000 churches and 1,000 Greek schools were built. Greek newspapers and books flourished, as did cultural and scientific societies.

During the Ottoman rule, many Greeks and other Christians in the Pontos region and the rest of the Ottoman Empire converted to Islam to avoid the persecution that came with the inferior ’dhimmi’ status. Yet, this ancient, vibrant community of Greek Christians remained until the 20th century genocide conducted by the Turks. Around 350,000 Pontian Greeks were massacred during the 1913-23 Christian genocide.

During the genocide, Greeks across Ottoman Turkey—in the Pontus region and Asia Minor (including Smyrna, Thrace, and other regions)—were also victims of Turkish persecution and atrocities. Christians throughout Ottoman Turkey (Greeks, Armenians, and Assyrians) were targeted with the aim of extermination through this genocide. The approximate death toll was around 3 million Christians. The surviving Greeks were deported from Turkey to Greece as part of the 1923 forcible population exchange treaty. The goals of these governmental policies were to wipe out Christians in Turkey.

The Sumela Monastery was also forcibly abandoned as a result of the genocide and the population exchange treaty. Following its abandonment, the monastery was vandalized, used by tobacco smugglers, and largely damaged by a fire. After renovations of the monastery, the Turkish government turned the historic monastery into a tourist site, forbidding it to be used as intended. This is an act of desecration of a historic and magnificent monastery. It is a blatant demonstration of Islamic supremacism.

Currently, the icons and murals in the Sumela Monastery have been vandalized so much that many of the figures are no longer recognizable. Greeks try to obtain permission to worship there for only one day a year (to celebrate the Dormition of the Mother of God on August 15), but Turkey obstructs even this single annual ceremony. Sumela, however, should have always been utilized by a community of monastics, monks, and nuns; this is the purpose for which it was built. This is required by a decent respect for religious liberty and civilization. Yet in Turkey, the vast majority of monasteries, churches, and cathedrals are not allowed to operate in their original forms. They are empty and neglected. Another example is the Vazelon Monastery in Trabzon.

As Christianity began to take root among the Greek population of the Pontos region, churches and monasteries were established. The oldest was Vazelon, or the Monastery of St. John the Forerunner. It is believed to have been built between 270 and 317. It was restored in the 6th century under the Byzantine Emperor Justinian, and then again in 1410. Alongside the Sumela and Kuştul (St. George Peristereotas) Monasteries, the Monastery of Vazelon was among the major monasteries of Trebizond. Much like the Sumela Monastery, Vazelon is located near a cave church at the foot of a cliff. Today the Vazelon Monastery is in ruins.

If the government of Turkey had some respect for Greeks and for early Christianity, and a little remorse for what it did to the local Christians, then it would restore those monasteries and allow them once again to operate not as tourist sites or ruined places, but as actual monasteries. Instead, the government is either trying to cancel worship ceremonies in those monasteries or letting them rot in ruins. The violations against Christians and their places of worship serve as a reminder of the Turkish government’s disdain for Greeks and for Christians.

Last year, some Islamist and nationalist groups also campaigned to cancel the August 15 liturgy at Sumela. A poster posted by a Turkish nationalist group read, in part: “Don’t hurt the bones of your ancestors, cancel the Sumela liturgy.” Ironically, most of the Muslim locals of that region (Pontos) are Greek, but they are unaware of this. A military of Muslim Turks from Central Asia invaded Anatolia (then part of the Byzantine Empire) in the 11th century and captured lands there. They invaded and seized Constantinople and Pontos in the 15th century. Millions of people in Turkey are descendants of Christians who had to convert to Islam throughout the centuries in order to survive.

The history of the indigenous Greeks and Christians of Turkey, however, has been virtually erased by the Turkish state. As a result, many Islamized Greeks in Turkey despise and distrust Christian Greeks without realizing that they have shared Greek ancestry. Naturally this additional tragedy is another consequence of the genocide itself and Turkey’s historical revisionism.

The latest stage of the Christian genocide is currently occurring in Turkey: the vehement denial of the genocide, the eradication of remains of the victims, and the destruction of their patrimony. To be a civilized member of the international community, Turkey should cure itself of its Christianophobia, and make peace with the fact that most of its inhabitants are Islamized Greeks, Armenians, or Assyrians.