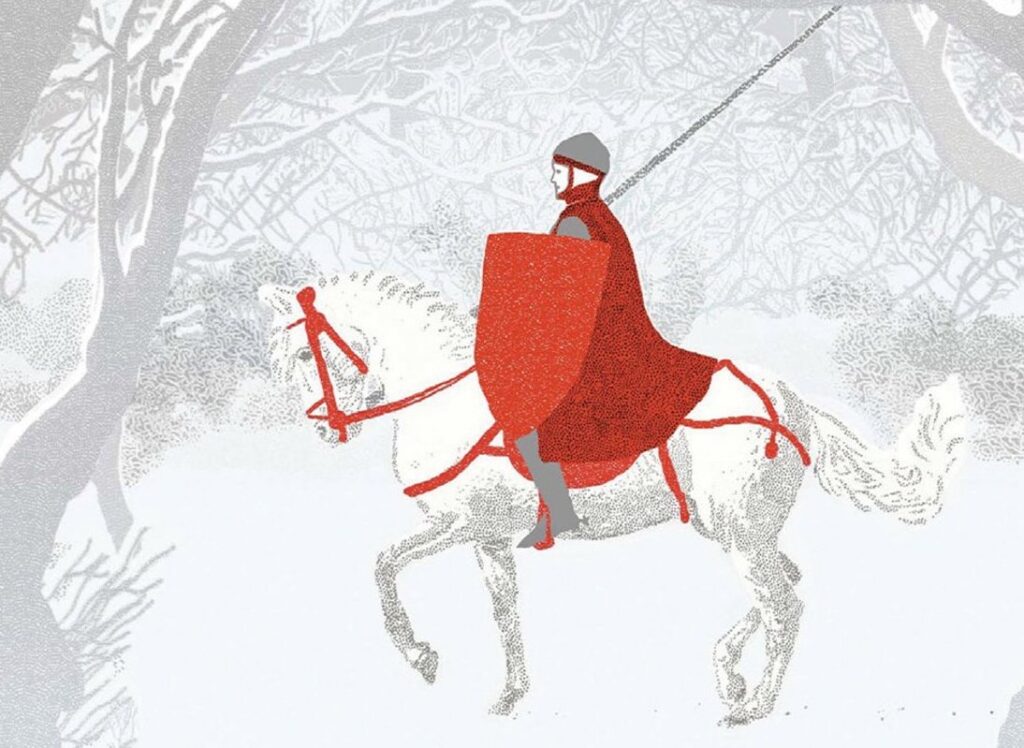

Sir Gawain is a dramatic tale of a knight’s bravery and chastity in the face of temptation and, crucially, the distinctive experience of grace and forgiveness that Christ’s birth, death, and resurrection has made possible.

“We don’t need any more evil in the world. We need a lot more reckoning with it.”

When we find ourselves at an impasse, it can be very helpful to look to great figures from history for guidance. Today, we could learn a thing or two about cultivating political culture from a universally-known but rarely studied figure, Charles the Great, or Charlemagne.

Waugh’s trilogy approaches war with a transcendent hope that is capable of withstanding the slings and arrows of modernity without losing itself.

Reading Sigrid Undset’s trilogy challenges readers to confront their own moral vacillations and need for constancy.

Lewis wants his readers to re-examine our presumptions about everything from modern education and science to ‘the West’ and contraception. Recognizing this can help us understand why the novel has so divided readers.

Whereas much science fiction simply sidesteps the theological questions a Christian would raise on discovering rational life on other planets, C.S. Lewis asks us to wrestle with them.

Judging by the 1942 film, the story of Bambi is a relatively simple and childish tale. True, it famously deals with Bambi’s loss of his mother, but in general the movie leaves viewers with the banal, sentimental, fuzzy feelings that has made Disney an entertainment juggernaut. But these are not the feelings Salten’s original novel produces, nor is the novel particularly intended for children. How, then, did Disney’s image of Bambi become the predominant one? And how does this story and its reception shed light on our current Western culture?

Norse mythology, unlike the Sacred Scriptures, does not present readers with loving and merciful divinities. The Norse gods are violent boozers, many of whom seem to spend most of their time playing practical jokes and fighting giants. And yet there is a great power to the tales.

How do localism and nationalism fit together? How do each of these philosophical approaches to place use and abuse the innate noble feeling of patriotism? Over the course of Chesterton’s story, we are challenged to confront these questions and answer how we ought to live.

The novel is compelling (even spellbinding at times)—and if it is called antiquated, it is only because we have forgotten that the oldest human battle is the worthiest one: the battle to achieve and maintain virtue in a fallen world.

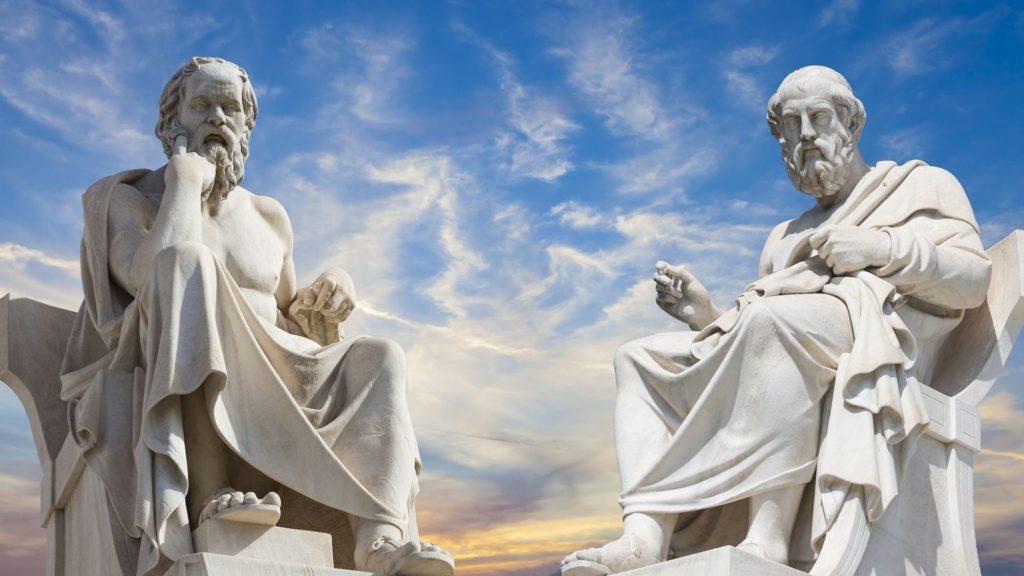

Without the Idea of the Good, Lloyd P. Gerson argues, a person cannot argue coherently against materialism, relativism, skepticism, mechanism, and nominalism.