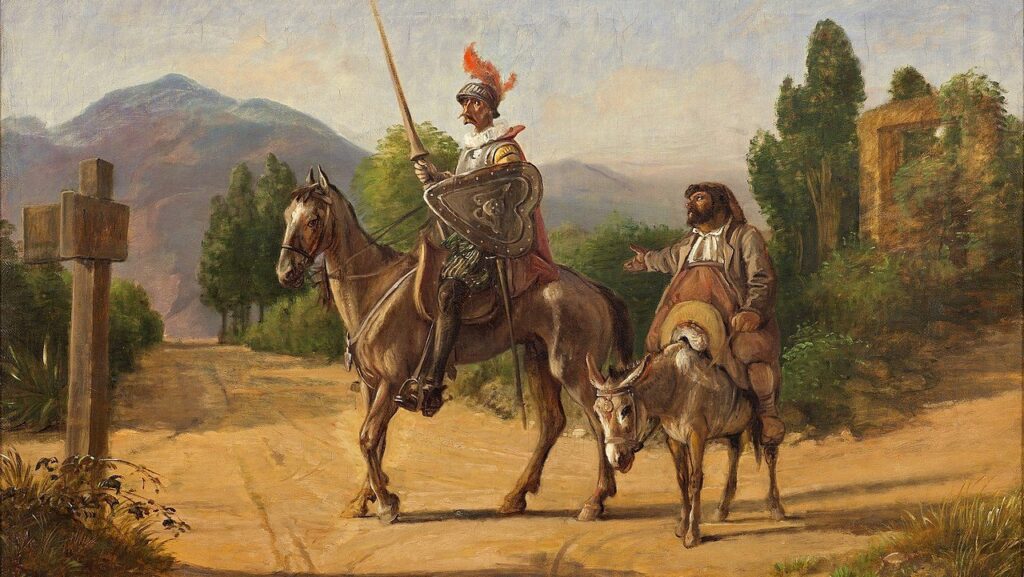

More than any other literary masterpiece, the novel Don Quixote received, upon its complete publication in 1615, a myriad of interpretations. As he prepared for his own immersion into the world of “the Knight of the Sorrowful Face,” the Hispanist Paul Alexandru Georgescu highlighted the gigantic dimensions of the specialized exegesis:

It is constantly reiterated that the vastness of exegesis dedicated to the works of Cervantes renders ten human lifetimes insufficient for its mere informative exploration—how many more, then, for organization, selection, and personal construction?—and, as such, the possibility of any original contribution in the field is excluded.

In such conditions, Georgescu asserts, it seems that “everything has been said, even if it’s not known by whom and where, on what shelf.” Nevertheless, despite this situation, in a volume published in the 1980s, the Romanian philosopher and mathematician Anton Dumitriu proposed an original interpretation of Cervantes’ work.

A passionate classicist, Dumitriu distinguished himself particularly through his studies in logic, philosophy, cultural theory, and epistemology. As a synthesis of his research, his History of Logic in four volumes was translated and published by Abacus Press (UK) in 1977. Besides his philosophical studies, he developed some interesting interpretations of the most important literary works of the Western canon. These were included in his book entitled Cartea întâlnirilor admirabile (The Book of Admirable Encounters), published in 1981. Here, among chapters dedicated to ancient authors like Homer and Orpheus, we also find interpretations applied to the classic creations of Miguel de Cervantes y Saavedra, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, and Dante Alighieri.

Opening Dumitriu’s monograph, the brilliant essay entitled “Don Quijote de la Mancha or the Inversion of the Human Condition” demonstrates the particular interest devoted to Cervantes’ work. Displaying his erudition, Dumitriu records the most well-known analyses of Don Quixote, showing that “in general, Spanish critics … have adopted only the opinion according to which Cervantes had no other purpose than to ridicule the knightly adventure writings, very fashionable at that time.”

Unlike those who follow this interpretation, Dumitriu suggests that we are instead dealing with “a universal symbol of man,” characterized by the strange convergence of contraries—wisdom and madness. Starting from an archetypal character in which he observes how wisdom metamorphoses into madness (or the reverse), Dumitriu presents an array of sources from various cultural and religious traditions, ranging from Sumer and classical Egypt to the various folk cultures of Romania, Germany, and even Persia. From all these, Dumitriu extracts the paradoxical concept of the wise fool, a figure exemplified in the Middle Ages by the role of the court jester. This paradigmatic figure demonstrates through its universal dissemination that “the origin of these age-old traditions, now incomprehensible, is the same, and that they derive from one another.” Continuing his meditation on Don Quixote, Dumitriu emphasizes the symbolic nature of “the Knight of the Sorrowful Face,” and he rhetorically asks, “How are we to decipher the symbol of Don Quixote?”

The method of interpreting works based on the symbolism of characters is an ancient one. For example, it seems that Roman philosophers in the era of Cicero staged—in the form of theatrical representations—Plato’s dialogues. One of the authors who influenced their understanding is the Neo-Platonist Proclus, who assigned precise functions to each character in the Timaeus dialogue. Knowledge of these functions is essential for achieving a sound interpretation of the philosophy of the founder of the Academy. Anton Dumitriu follows this method of interpreting literary works, investigating the symbolic value of characters—through which he unveils meanings undiscernible to those who are unfamiliar with it.

From this perspective, “Don Quixote is a symbol of human universality,” illustrating the journey that every soul must undertake to free itself from the illusion, both cognitive and ontological, that has held humanity captive since expulsion from Paradise. Although the events experienced by Don Quixote are effects of his disordered imagination, “one thing remains strictly accurate: the scenario based on an initiation.” In fact, what Cervantes wishes to convey is “the mythological meaning of the world,” taking as the main theme of his works the unfortunate inversion suffered by fallen man. Essentially, Cervantes aims “to depict through the grotesque a reversal of the primordial order.” His literary creation is constantly animated by the “idea that there is a path that leads to the restoration of human being through experiences hierarchically organized in an ascending ladder.” Caught in the web of an illusion, or rather a nightmare that places him beneath the plenitude of his prelapsarian condition, man can liberate himself by traversing in reverse the path of his descent, ascending towards the proper state of human existence through a struggle in which he confronts the phantasmic giants that surround him.

Don Quixote proves to be a man for whom reading stories of chivalry is insufficient. He wants to experience firsthand the medieval chivalric code, delighting in the fruits of fidelity to its principles. Don Quixote is seeking a true king capable of rewarding his valiant deeds. The rest no longer matters. Unlike Saint Ignatius of Loyola, who renounced worldly honors to become a ‘knight’ of the Militia Christi, the aged hidalgo commits himself decisively to deeds of arms. These deeds are more real to him than the illusory reality of a declining world. Paradoxically, through our hero, one of the fundamental archetypes of Christianity is revealed to us: chivalry concealed beneath a cloak of humility.

Appearing mad in a world that no longer appreciates nobility, holy knights, like those for whom the great Bernard of Clairvaux wrote in De laude novae militiae, remain ever-present. They will never disappear, supported by the divine glory of the crucified Christ. Tasting the bitterness of an age that extolled Chivalric virtues only when they were confined to the pages of adventure books, Cervantes accurately described the condition of the hidden knight. Practicing Christian virtues, ridiculed precisely for this reason, he becomes a valiant fighter against windmills. Why does this happen? Because, as is evident from the teachings of Saint Paul, there exists an unavoidable conflict between “divine wisdom” and “worldly wisdom.” And Don Quixote ardently loves only divine wisdom. Tirelessly pursuing his ideal, he sees ladies, knights, princes, giants, and he sees justice where there are only harlots, greedy innkeepers, thieves, lies, and hypocrisy. A miracle occurs before the astonished eyes of the reader: the “madman” discovers what he is seeking! And this discovery, it turns out, remains perfectly possible anytime, anywhere.

We find ourselves, today, in a situation not dissimilar to that of the early Christians. Practicing virtues and battling unruly passions propel us into an unseen war fought “not against flesh and blood; but against principalities and powers, against the rulers of the world of this darkness, against the spirits of wickedness in the high places” (Ephesians 6:12). This struggle takes place in the core of our being. Anticipating this phenomenon of internal chivalry, accompanied by the ridicule that results from habitually practicing its principles, Cervantes deserves credit for having described, in terms understandable to all, the condition of any Christian who opposes the cultural models of a corrupt and corrupting world.

If anyone wishes to conquer the giants of their own vices, they must, like Don Quixote, take up the lance, the shield, draw down the visor, and mount Rocinante. Though in the eyes of many, such a “politically incorrect” knight appears ridiculous, we have no doubt that his deeds will be as resonant as the adventures of Don Quixote. According to the Spanish man of letters Don Miguel de Unamuno, the recipe for success is always the same:

Set forth! They demand to know where? The star will make it clear: to the Sepulcher! What will we do on the road as we advance? What shall we do? We shall do battle! And how shall we battle? How? When you encounter a liar, shout in his face ‘Liar!’ And press forward! When you encounter a thief, shout ‘Thief!’ and press forward! When you encounter a man who talks nonsense, one to whom the crowd listens openmouthed, shout ‘Idiots!’ And press forward! Always press forward!