Attempting to expound someone else’s thought is always a high-risk endeavor. But since I recently declared Dalmacio Negro Pavón the most significant political thinker in Spain in recent decades, with all due caution, I will outline what I consider to be some of the interpretive keys to Negro Pavón’s thought.

The work of Dalmacio Negro Pavón reveals that politics cannot be understood without anthropology: the various conceptions of humanity throughout history are not mere theories but paradigms that have shaped the lives of peoples and conditioned political thought.

Some artists and writers attain great renown in their own lifetimes. Others toil in relative or complete obscurity only to garner fame after death. Kafka and Stieg Larsson, John Kennedy Toole and Emily Dickinson seem to belong in this latter category. Still others, while not unknown during their lives, are ‘upgraded’ after death, acquiring a respect and broader literary acceptance that they never had in life. An example of this is the posthumous acceptance of H.P. Lovecraft and Philip K. Dick into the august canon of the Library of America.

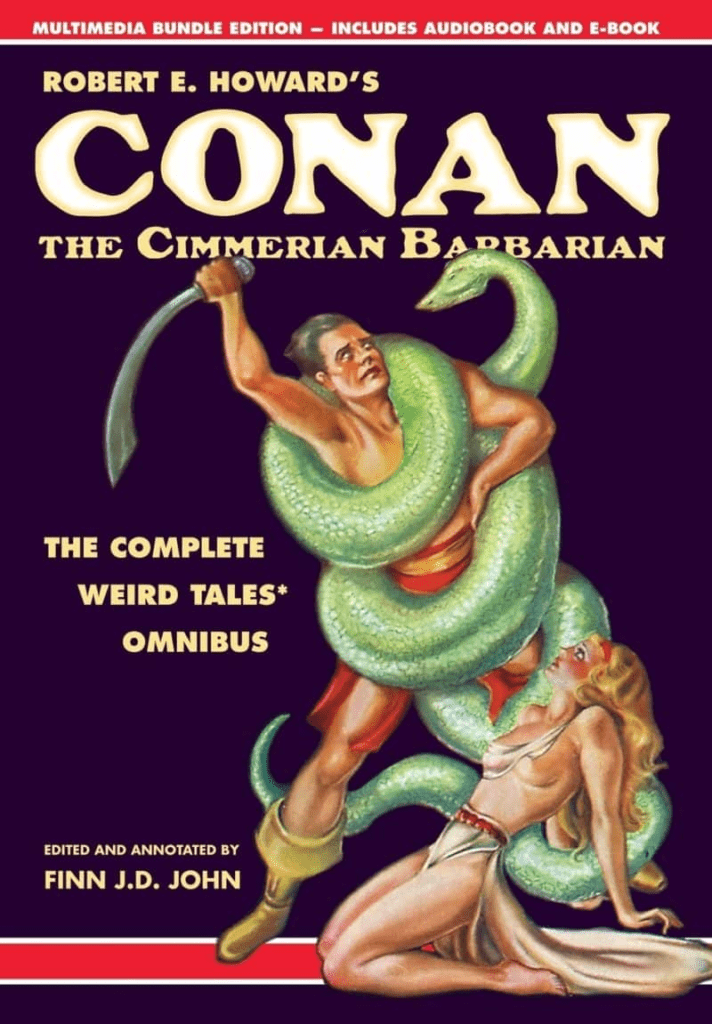

Lovecraft’s younger peer in the pages of the horror-genre Weird Tales magazine, Robert E. Howard (1906-1936), has also had a lively literary afterlife, although not quite reaching the heights of those others. The author of the stirring tales of Conan of Cimmeria and Solomon Kane has had six films, mostly bad ones, made from his work. A seventh film, “The Whole Wide World,” was made about Howard himself, played by Vincent D’Onofrio. Much of Howard’s work slowly appeared in hardcovers in the 1940s and 50s before booming in paperback in the 1960s and 70s. This was spurred by iconic art from the likes of Frank Frazetta, the Michelangelo of paperback covers. The popularity of Conan of Cimmeria in those years led to dozens of mostly inferior pastiches of Howard’s work by contemporary authors; comic book and graphic novel adaptations followed. Some later writers with their own distinctive style—Fritz Leiber Jr., Karl Edward Wagner, David Gemmell, even Stephen King—have praised Howard’s work.

Despairing from family tragedy and dying by his own hand at the age of thirty, Howard’s work is that of a very young man who was a gifted storyteller. He had been a prolific published writer for twelve years and had succeeded in making a hard living from it, in the teeth of the Great Depression. Born and raised in rural Texas, where he remained most of his life, he was a product of early 20th century Anglo-American culture. He was “mainly Irish and Norman, with the Irish predominating,” with Southern roots (both his maternal and paternal grandfathers fought for the Confederacy), and a Westerner.

Two recent American novels feature not the vivid characters who were products of Howard’s imaginative pen, but fictionalized versions of the man himself. Teel James Glenn’s A Cowboy in Carpathia was published in 2020 by Pro Se Press. David Pinault’s Providence Blue appeared in 2021 from Ignatius Press. Two very different books from two very different publishing houses. Ignatius Press is a respected Catholic publisher, while Pro Se Press’s goal is to produce “new pulp” genre stories that are “written with the same sensibilities, beats of storytelling, patterns of conflict, and creative use of words and phrases of original Pulp, but crafted by modern writers, artists, and publishers.”

Providence Blue by David Pinault, San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2021; A Cowboy in Carpathia by James Glenn, Batesville, Arkansas: Pro Se Press, 2020.

Featuring a lurid cover seemingly torn from a Blacula film poster, Glenn’s Cowboy in Carpathia is a fast pulpy delight by a writer who knows his Howard history. In this alternate universe, Howard doesn’t kill himself in June 1936. Instead, he goes on to have adventures in New York, England, and Continental Europe, battling supernatural threats and rescuing the woman he loves. Here is Howard, the poet and teller of tales, and also the real-life big bruiser who knew how to box, ride horses, and fight bullies and oil field toughs. The book promises to be part of a “Bob Howard Adventure” series, which sounds like a grand idea. One can imagine enjoyable future yarns of two-fisted Bob Howard shanghaied on the South Seas or fighting Nazis or meeting up with Lovecraft to battle supernatural evil in the French Quarter (although real life correspondents, Howard and Lovecraft never met. Lovecraft made it once to New Orleans in 1932, but Howard lacked the money and car to meet him there).

Glenn’s humble and affectionate tribute to the Bob Howard that might have been works because it is unpretentious and well-grounded in his subject’s own words and mindset. It also moves with a pace reminiscent of the pulps.

Providence Blue is nothing if not ambitious in its literary and philosophical aspirations. No pulp is found here. It also begins with Howard deciding whether or not to kill himself. Here he does commit suicide and becomes a “vespertine” spirit caught between the afterlife and other lives. He is more a MacGuffin than a protagonist in a convoluted tale that also involves a villainous Lovecraft, the spirits of Poe and Melville, Howard’s one-time girlfriend Novalyne Price, and a host of characters set in modern-day Providence, Rhode Island.

I wish that I liked the book more because Pinault is a very talented writer and there are some vividly drawn scenes and affecting characters with a strong sense of place. A good book could have been made about fantasy misadventures in Roman Nubia, about quirky loves Joseph and Fay or about the good priests Father James Cypriano and Monsignor Emile Bergeron, but not about all three storylines (and several more) in the same overstuffed volume. Still, both books are testimony to the enduring appeal not only of Howard’s writings but of the tragic and talented young man himself.

The real Howard was rather more interesting as an example of a humble but sturdy tradition of the adventure writer in popular literature, especially Anglo-American writing from the late 19th century on. With due respect to the august shades of Alexandre Dumas, Jules Verne, Emilio Salgari, and Karl May, this is a genre in which English-language authors have particularly excelled. The most numerous works in Howard’s own personal library (donated by his father to Howard Payne College after the young man’s suicide) were books by Tarzan creator Edgar Rice Burroughs (12 volumes), Arthur Conan Doyle (10 volumes), and then tomes by Sax Rohmer, Talbot Mundy, Robert W. Chambers, Rudyard Kipling, Jack London, H. Rider Haggard, and Harold Lamb.

Le guide Howard by Patrice Louinet, Chambéry: ActuSF, 2018.

Some of those writers, and Howard himself, were in turn influenced (as J.R.R. Tolkien was) by the heroic myths and legends of Europe. In Howard’s case, both Irish and Norse traditions prevailed. He once wrote that he’d rather be a Goth than a Roman. It appears that Europe is likewise inspired by the author. Since the 1960s, there has been a steady translation of the Texan’s work into European languages, including French, Spanish, Italian, German, Dutch, and Russian, among others. One of the great Howard scholars working today is the Frenchman Patrice Louinet.

Howard’s town was too small to have a full-fledged high school, and he had to move 35 miles away to complete secondary school. He “hated” school but loved to read. In many ways—although his father was a country doctor—he was a blue collar, self-made working writer, dreamy and poetic but also driven to succeed and influenced by his rough-hewn surroundings. As his best biographer Mark Finn notes, living in barely settled rural Texas and given his father’s profession, Howard was exposed to “a lot more gore and mayhem than the average frontier kid.” Writing for him was both the exercise of a fertile imagination and a practical means to freedom from the drudgery of modern working life.

Although he attained his initial fame in Weird Tales, he wrote almost anything he could to make some money and would add a fantasy or supernatural element to adventure stories in order to sell them. Decades after his death some of Howard’s historical adventures were in turn rewritten as Conan of Cimmeria fantasy adventures.

His preference lay elsewhere: “I wish to Hell I had a dozen markets for historical fiction—I’d never write anything else.” The father of the Sword and Sorcery genre, many of his best tales are historical adventure fiction set in the lands of the East (most can be easily found in the 2011 collection Sword Woman and Other Historical Adventures). Other historical fantasies are set in Roman Britain. One rousing tale, about the 11th century Battle of Clontarf in Ireland, was written as a historical adventure. It was rejected by one pulp magazine, rewritten as a fantasy for Weird Tales, rejected by the editor, and then rewritten as a horror story to be published in Strange Tales in 1933. Even Howard’s fantasy tales of Conan the Barbarian, who becomes king by his own hand in an imaginary realm resembling Merovingian France, could easily be about a fictionalized Alaric the Goth or Odoacer, Robert Guiscard or Charlemagne.

Other Conan stories resemble Westerns, and in his last years, Howard seemed to be moving in that direction. He mused about the great literature that would be written about his own American Southwest yet to come, “epics of exploration, conquest and settlement.” In addition to vividly writing about imaginary lands or medieval Europe, Howard was deeply attached to his place and people, with Texas looming almost as large as Conan’s Hyborian Age or Solomon Kane’s Africa. Had he lived, he might have become another Louis L’Amour, a writer renowned for his Westerns. L’Amour’s 1984 medieval adventure The Walking Drum has echoes of Howard.

Howard, the writers who influenced him, and many of those that came after in the same heroic vein seem more outside the pale of literary respectability than they would have been a century ago. It is not just the artificial divide between Literature with a capital L and popular genre fiction, or the modern disdain for the writers of the past. The even greater divide is between unironically portraying heroism in the West and despising it and deconstructing it in order to bring about its demise. There are, thankfully, still great, popular writers of historical adventures; Bernard Cornwell and Arturo Pérez-Reverte are two examples. But just as the Western presented in a heroic or positive light has become unfashionable, so are crusaders, knights, and conquistadors seemingly out of touch. Compare the mewling, doubting hero of Ridley Scott’s influential 2005 film Kingdom of Heaven to Howard’s grim crusaders and knights. These are tough men, often exiles, mostly betraying and killing their foes before dying themselves. Still other Howard heroes are more contemporary, like Francis X. Gordon, the Texas gunslinger turned rambling Middle East adventurer. None of his heroes are mewlers.

One of the reasons, perhaps, for the growth of comic book heroes splashed on the big screen by the likes of Marvel and Disney, or fantasy and science fiction characters, may be because real historical heroes are decidedly unpopular,as unfashionable as traditional masculinity, patriotism, and real sacrifice —for an actual nation, a family, or a faith—are in the West. Imaginary heroism against Orcs or giant robots is one thing. Remembering or honoring historic heroism against the Turks or Aztecs seems to be something else. And even worse, some of the splendid panoply of European and American history has been shunted aside by the mainstream only to be picked up and repurposed by far-right or identitarian groups. As Napoleon once said, “it is with baubles that men are led.” We should be thankful that Aragorn son of Arathorn and Conan of Cimmeria are fictional characters so that boys and young men can still safely dream of glory and victory without those dreams being taken away.