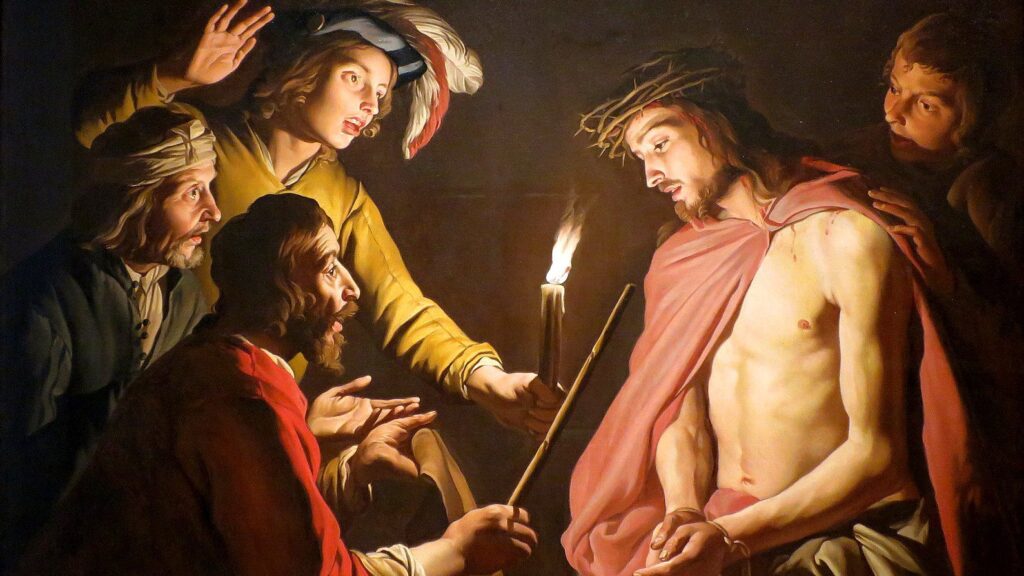

Christ Crowned with Thorns, (between 1633-39), a 110.8 x 161 cm oil on canvas by Matthias Stom (c. 1633–1639), located in the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena, California, U.S.A.

The 40 days of Lent are, for Christians, an ideal time to reflect on Christ’s Passion, death, and resurrection. Many great artists have captured these events in beautiful paintings, poetry, prose, and most of all, music. Towering above all Passion-related music are the monumental and seminal Passions by Johann Sebastian Bach, most notably the Matthäus-Passion (St. Matthew’s Passion) (1727) and the Johannes-Passion (St. John’s Passion) (1724). His lesser-known passion is the Markus-Passion (St. Mark’s Passion). It is little known for a good reason: it was lost. But recent scholarship has enabled a reconstruction, and the result is something to behold.

“Whereas the Matthäus-Passion and Johannes-Passion are extremely well-known and have long and well-established performance traditions, the libretto of the Markus is largely unknown, even to Bach scholars. It was conceived on a much smaller scale than the others, with fewer arias and a greater number of chorales, so it was difficult to get a sense of the overall arch of the piece and the pace of its narrative until the final rehearsal,” commented Tom Neal, Director of music at New College School, Oxford, who recently conducted a reconstruction of the Markus-Passion in the chapel of his college.

According to his obituary in 1751, written by his most gifted son, Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, J.S. Bach composed no fewer than five Passion settings. One of these was an early versified Passion-Oratorio (1717) and perhaps a St. Luke’s Passion. With the Oratorio begins the story of the Markus-Passion.

In the 19th century, there was no trace of the Markus-Passion in autograph or printed score, and in the 20th century, its only known source was an incomplete copy in the hands of Bach manuscript collector Franz Hauser (1794-1870). The score had not yet been scrutinized when it tragically fell prey to fire in 1945 in Weinheim during the Second World War.

In the last 150 years, it became a commonly accepted notion that Bach’s St. Mark’s Passion must have been a ‘parody,’ meaning that it was based on recycled musical material, as was commonplace in the 18th century. This was the nature of his Mass in B minor. Additionally, in 1730, Bach had asked Christoph Friedrich Henrici (Picander) to write a libretto for the Passion for a small performance in 1731, which presents us with the text as a basis for a reconstruction.

Due to the presence of that libretto and the knowledge that the basis for the Markus-Passion was the funeral music of 1727, Trauerode (Ode of mourning) (BWV198), Wilhelm Rust, an editor of the Bach Gesellschaft, was able to see the similarities between the Trauerode and the Markus-Passion, both of which were scored for a unique combination of strings and winds with the addition of two viols and two lutes. With Picander’s libretto extant from other 18th-century sources, Rust compared the opening chorus of the Trauerode with the Markus text. The scansion, i.e. the rhythm of a line of verse, of text to music proved perfect for the opening and closing choruses, as well as for the arias “Er kommt,” “Mein Heiland,” and “Mein Tröster.”

Rust’s discovery would trigger years of musical detective work in search of further suitable parodies.Recent scholarship in Germany and Great Britain has further added to the reconstruction and has led to a ‘miniature Passion’ which was most recently unified by Malcolm Bruno in 2005.

“Malcolm Bruno has been careful to follow the evidence, where it exists, in tracing which pieces Bach might have parodied or reused in the Markus—there are several movements from the Trauerode (BWV 198), for example,” Neal commented. He added,

Occasionally he has transposed or rescored a movement which otherwise fits well, adopting basic procedures which Bach himself is known to have used in similar situations. In my view, the success of Bruno’s edition lies in its restraint. Unlike Ton Koopman (in his more speculative reconstruction of the Markus-Passion, recorded in 2019), Bruno has not composed any new music; all of the music is Bach’s. Rather than compose pastiche recitative, for example, Bruno has simply left the text unset, suggesting the text be spoken instead. Before the performance, I was concerned that switching between music and spoken text would disrupt the flow of the work, but both performers and audience reported that hearing the narrative read aloud encouraged those present to follow the narrative more closely; consequently, the arias such as St. Peter’s ‘Erbame dich,’ had even greater emotional impact.

In his well-founded and dense study on the subject, Malcolm Bruno notes:

It is in this context that we will always approach the Markus: before the great St. Matthew, with double choir and double orchestra, and the swifter and more compactly moving St. John, in its different versions, and indeed, in the final horizon of J.S. Bach’s creativity, in his [B minor] Mass. The enigmatic Markus remains the most intimate of all, though only partially in view to us, like an ancient torso not having survived the ravages of time … giving us the most exquisite ‘miniature’ Passion imaginable.

Tom Neal is optimistic about the reception and performance of this newly found gem:

I very much hope other choirs take up this wonderful new edition. The instrumental parts are challenging and really need to be tackled by specialist baroque players, but the choral parts are perfectly manageable by good amateur choirs, and the four solo roles are not overly taxing. Bruno’s edition is a welcome addition to the Passion repertoire and, along with Handel’s Brockes Passion which I directed a few years ago, provides an attractive alternative to the two ‘great’ Bach Passions.