At the most fortunate moments in history, when we have felt exhilarated and ready to move forward, and indeed have moved forward, our determination has been accompanied by a sense of reverence for the past. This awareness of yesterday has served as our fulcrum, that which gives meaning to the present and projects it into the future. The present is not, as it might seem to those who insist on living in the moment, a place floating nowhere, but a solidly rooted tree, with deep roots, from which vigorous branches sprout, challenging the sky.

For some time now, however, the past has been subjected to a collective admonition that began by distorting it and then emptied it of all its achievements, condemning it to oblivion. Today we are left with, if anything, a circular idea of progress, what they call progressivism: the search for a happy and secure world in a continuous present that turns us into castaways of time.

Unfortunately, the present alone is a scarce food, incapable of satisfying the hunger for meaning inherent in human beings. No matter the era, the meaning of life, the reason for existence is as disturbing and incomprehensible to us today as it was 25 centuries ago. That is why our ancestors recreated the great events, and revered what they had been taught at home, at school, and in the temple. They knew, as we know today, that everyone’s life is extremely brief and inconsequential when considered on its own narrow terms, and so they decided to embed it in the idea of progress, to give it meaning. This, however, did not imply renouncing individual identity or religious beliefs; it meant sharing a common framework of understanding in which the past was an indispensable reference.

When we deny the past in order to free ourselves from attachments and live only in the moment, seeking immediate satisfaction and self-affirmation, we become hungry predators that prowl around the present, as if it were famished prey—wolves condemned to devour the same fleshless sheep day after day, eternally, without ever being able to satiate ourselves. But, although as predators we prowl together, we are not even a pack because nothing unites us except hunger. We are isolated from each other. And the distance between isolation and self-destruction is very narrow.

In these post-COVID times, experts warn that depression, anxiety, and stress will be the next pandemics, but the truth is that depression was already a pandemic well before 2020. In January of that year, it was estimated to affect more than 300 million people worldwide and one of its consequences, suicide, was responsible for at least 800,000 deaths each year. In individuals aged 15-29, suicide was no less than the second leading cause of death.

Something was already rotten if many of our young people, instead of eating up the world, were opting to leave it tragically and prematurely. And that many others, especially in Anglo-Saxon countries, developed an extreme sensitivity not just to the natural adversity of existence, but to any idea, statement, or opinion that might be the least bit disturbing to them is further proof of fragility.

Many even seem to have decided that the mere existence of debate is an intolerable burden. It is a little less than a decade since the alarm bells were sounded about this youthful hypersensitivity. Since then, numerous authors have tried to unravel its causes and propose solutions, apparently without much success, since, far from abating, the problem continues to worsen. In a recent essay addressing the problem, “The Transformation of the Modern Mind,” Jonathan Haidt and Greg Lukianoff draw on the idea that the “culture of dignity”—said to have replaced the “culture of honour”—has in turn been supplanted by a new “culture of victimhood.” This means that any word, statement or disagreement, however insignificant or unintentional, is liable to be lamented as an unbearable form of aggression, particularly if the dynamic occurs between an alleged oppressor and an ostensible victim.

Haidt and Lukianoff offer cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) as a possible solution to the idea of the culture of victimhood, an idea originally developed by sociologists Bradley Campbell and Jason Manning. Since feelings tend to confuse us, we can only achieve mental balance if we learn to question them and free ourselves from distortions of reality. Thus, as Haidt and Lukianoff explain, CBT helps us to realise when we are developing “cognitive distortions” like catastrophism or what they call “negative filtering,” which consists of attending only to negative criticism, instead of valuing positive criticism as well.

The efforts of these authors and many others to provide tools with which young people can confront and overcome their alarming fragility, and thus become resilient and mature individuals, are to be welcomed. However, their book is still very much a self-help manual which accordingly looks at reality from a narrow perspective. The problem is that experts tend to confine problems, however complex and profound they may be, to their own area of specialisation. That is why until not so long ago there was a hierarchy between intellectuals and experts. Today, however, a cult of empiricism, despite its enormous limitations, has placed experts in a predominant position. And the public intellectual, or philosopher, practically extinct, has become typecast as a guy who develops bizarre hypotheses that cannot be proven.

Be that as it may, questioning microaggressions, even ridiculing the notion at the level of rational argument, is not enough. Nor is it enough, however useful, for CBT to survive in a world that has validated misguided and extremely corrosive ideas and attitudes—beliefs, in short, which are contrary to human nature itself and the roots of which, it seems, neither Haidt nor Lukianoff really question. If anything, quite the contrary: they assume them as an inevitable landscape, even confusing them with good intentions.

Some years ago, an acquaintance who was going through a rather bad situation, both personally and professionally, went to a psychiatrist because he was feeling quite depressed. When he had finished explaining his circumstances, he looked at the psychiatrist in anguish and asked: “Am I crazy?” The psychiatrist smiled piously and replied: “No. You have more than enough reason to feel quite depressed.” This anecdote serves to separate the hypersensitivity of many young people from a deeper problem for which there is no therapy: the insanity that seems to have taken hold of our environment.

Expecting young people to survive in a world where prevailing ideas defy logic, and where, not in their opinion, but in the opinion of their teachers, they have to disavow their origins, their history, their past, the customs of their parents and grandparents, to float adrift in a designer present, at the whim of a handful of ideologues, is like expecting them to pass a special operations corps survival test for which only a select few are fit.

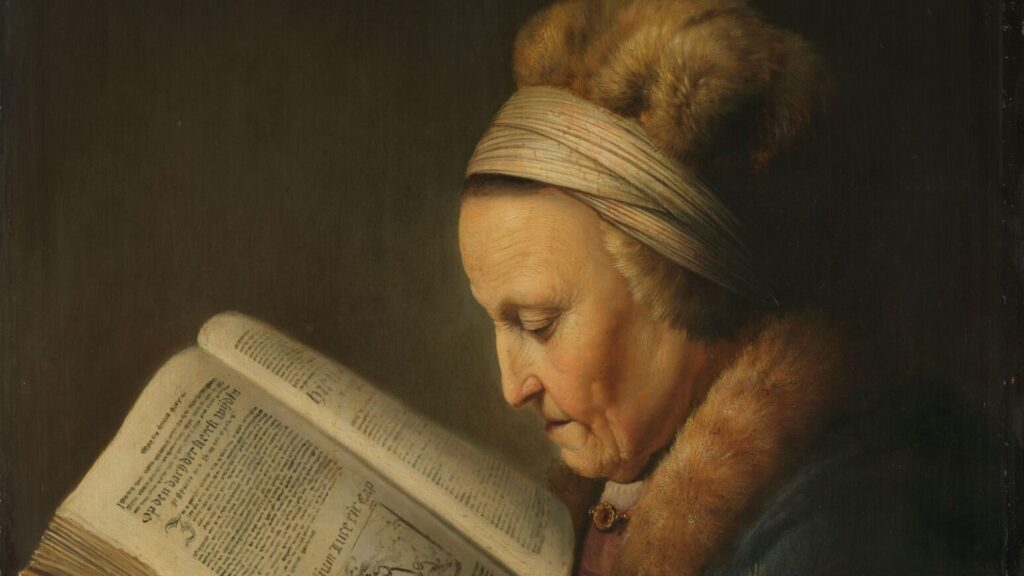

Not so long ago, when a young person was confused and did not know how to deal with a situation, they sought advice from their elders. Today, by contrast, they too often turn to psychologists. Grandparents are no longer useful. In fact, they have become a nuisance when it comes to rushing through the present. That is why we abandon them in old people’s homes, where they languish and die in silence—a reality that was exposed during the pandemic, to the shame of all concerned.

A society that neglects its elderly, that deliberately ignores them, will hardly be able to develop a genuine love for its children and, consequently, will not look after them properly. If anything, it will provide them with comforts, entertainment, and whims; in other words, it will make them pampered—in exchange, of course, for not making a nuisance of themselves. In the same way, a society that denies its past will not be able to project itself into the future.

Cognitive behavioural therapy can be used to treat those patients who exhibit their own singular distortion of reality. But when this distortion is collective, perhaps the problem is not so much psychological as one of cultural education and social knowledge. If so, it would be enough to teach what critical tolerance, freedom of expression, the presumption of innocence, pluralism and debate really are and why they are so important. It can also hardly hurt to mention as well that it is thanks to the past that all these things exist at all. Perhaps, in the end, young people—and adults too—need something positive to believe in, rather than a vapid children’s story whose happy ending, impossibly enough, is depression, denial and anger.