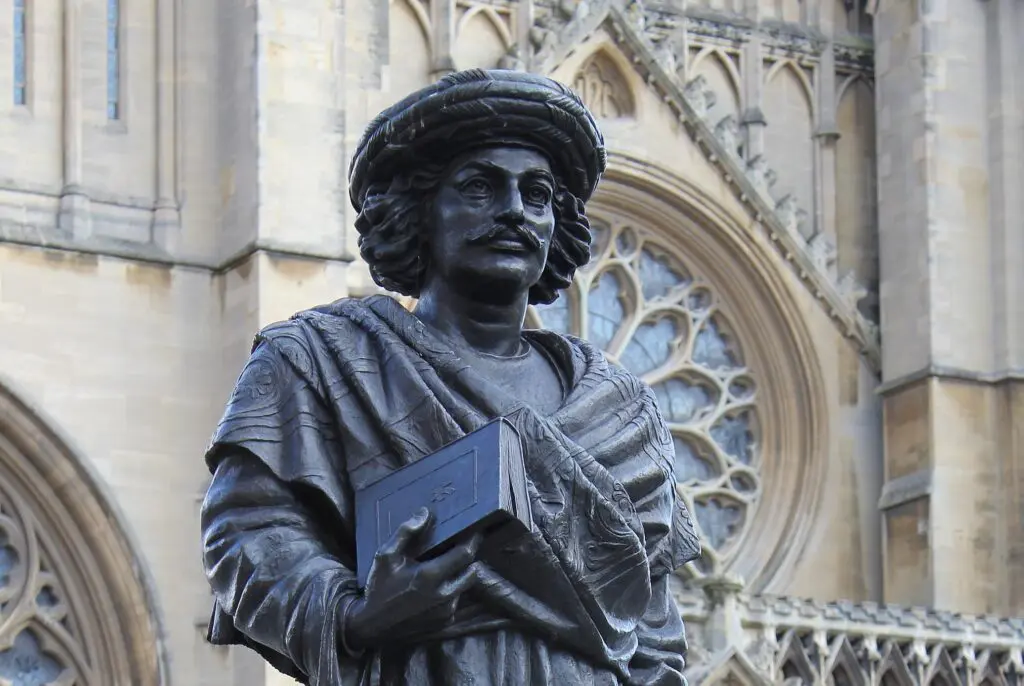

Statue of Ram Mohan Roy (1772-1833), an Indian religious social and educational reformer, in College Green, Bristol, England.

Last October, the acting vice-chancellor of Cambridge University, Dr. Anthony Freeling, made a confession, widely reported in the press. He confessed that he is baffled by ‘decolonisation.’ The word, he said, “has been misused to such an extent that I don’t think, if I’m honest, I can give an accurate definition.” I sympathise with his bafflement as do, I strongly suspect, millions of others. That’s because ‘decolonisation’ can mean a variety of different things, some of which make good sense, but others, very bad sense indeed. And the bad ones smuggle themselves into university departments under cover of the good.

The original and most natural home of ‘decolonisation’ is in former British colonies. There it can mean something entirely reasonable. For example, in 1986 the Kenyan novelist and playwright Ngugi wa Thiong’o published a book with the title, Decolonising the Mind. Here he argued that African literature should be written in African languages, such as his own Gikuyu. Why? So that Africans can recover a sense of self-respect and stop being in thrall to the assumption that whatever comes out of Europe is better. To which the only sensible response is: Yes, of course.

When translated out of its original, post-colony context and into contemporary Britain, ‘decolonisation’ can still make some good sense. It can mean correcting the neglect in school curricula of the history of immigration and the contribution of immigrants to this country. Or it can mean that important texts that have been excluded from reading lists in schools and universities, just because of prejudice against the race of their authors, should be included. If it is true that the history of immigration and the multicultural reality of Britain has been neglected, and if it is true that important texts have been excluded just because of the colour of an author’s skin, then curricula should indeed be ‘decolonised.’ Only, though, if those things are true—and have been shown to be true. So far, so much good sense.

Less reasonable, however, is the opposition of ‘decolonisers’ to ‘Euro-centricity’ and their insistence on shifting attention to non-European histories and cultures. On the contrary, a certain Euro-centricity in British education is entirely justified. Britain is not anywhere. We are located in north-west Europe, we have a particular history, and we have developed particular institutions and traditions. It’s vitally important, therefore, that school education at least should focus on helping budding citizens understand the immediate cultural and political environment in which they stand and for which they are about to become directly responsible. Of course, once at university, students can throw off Euro-centricity to their heart’s content and immerse themselves completely in African culture, Indian history, and Chinese language, if they so wish.

Equally unreasonable, I think, is the claim that school and university reading-lists should contain an ethnic diversity of authors, so that an ethnic diversity of students can identify with them. I say this because it seems to me manifestly untrue that people of a certain race can only relate to, understand, be inspired by, and learn from, someone of the same race. White Britons have been admiring the Semitic Jesus for two millennia and the Indian Mahatma Gandhi for over a century. And judging by the occasion on Christ Church’s high table ten years ago, when I was surrounded by a troupe of Shakespearean actors from Kabul, Afghans are perfectly capable of appreciating England’s most famous dramatist. Most happily, we really aren’t intellectually imprisoned in racial silos.

So, some kinds of ‘decolonisation’ make good sense and some not so good, but the one that should worry us most, I suggest, is that which tells the following story:

Britain is a systemically racist country.

Its racism is rooted in its colonial past, which it continues to celebrate, not least in the form of public statues.

And the epitome—the essence—of this colonial past was slavery, in which Britons treated Africans as sub-human.

This view of Africans as subhuman expanded into a wholesale disparagement of non-white cultures.

Therefore, we need to exorcise, to expel this lingering racist mentality by repudiating Britain’s colonial heritage.

That’s the cultural revolutionary ‘decolonising’ story that smuggles itself into university departments under cover of more reasonable ideas. And it’s a false story—false because every one of its main assumptions is wrong.

Why I think that, I’ll explain in a moment, but first let me tell you why I think you should care. There are lots of people on the Left, and some on the Right, who think that the present ‘Culture War’ is either a mendacious distraction or a futile one. I could not disagree more strongly. In my view, the colonial front in the ‘Culture War’ is culturally crucial; and since politics is downstream of culture, it is politically crucial, too. Why? Because what is at stake is the self-confidence of the British and their identity as a people committed to supporting and promoting a liberalising international order.

I first became aware of this when reading about contemporary Scottish nationalism. There is a strong strain in Scottish nationalism, as there is in Corbynite socialism, which believes in the equation, ‘Britain equals Empire equals Evil.’ By ‘Empire’ here is meant, not only Britain’s imperial past, but her present aspiration to retain her global role. According to some nationalists, therefore, for Scotland to separate from England, to dis-integrate the United Kingdom, and so to undermine one of the pillars of Western hegemony would be an act of national repentance and self-purification.

In his 1930s novel, A Man without Qualities, which was set in the decline of the Austrian Empire around 1900, Robert Musil wrote “However well founded an order may be, it always rests in part on a voluntary faith in it … once this unaccountable and uninsurable faith is used up, the collapse soon follows; epochs and empires crumble no differently from business concerns when they lose their credit.” Scottish nationalism, together with far-Left socialism, have not only abandoned the British faith; they actively seek to undermine it.

If it were true that Britain’s three-hundred-year imperial career as a global power was nothing but a litany of racism, cultural contempt, exploitation, and violence, summed up in the perpetration of slavery, then, far from identifying with it, we should repudiate it. We should even stop trying to keep the UK united.

So, the reason why ‘decolonisation’ matters is because of the story it tells about Britain’s present and past, and of what that implies for Britain’s future. Since I think that the story it tells is very largely untrue, even fraudulent, the danger that ‘decolonisation’ poses is that of persuading the British people to chart a course into the future that is based on a lie.

In 1976, the Baghdad-born Jewish historian, Elie Kedourie, published his book, In the Anglo-Arab Labyrinth. Here he argued against the belief that Britain had betrayed the Arabs during World War I, a belief that had come to infect the British Foreign Office. Chapter Seven closes with this sentence: “No doubt, great Powers do commit great crimes, but a great Power is not always and necessarily in the wrong; and the canker of imaginary guilt even the greatest Power can ill withstand.” Britain is no longer a great Power, but we are still an important Power. And we are an important liberal Power at a time when illiberal forces in Moscow and Beijing are flexing their brutal, authoritarian muscles on the battlefields of Ukraine, the streets of Hong Kong, and across the narrow water from Taiwan. So, the reason why cultural revolutionary ‘decolonisation’ matters—and why you should care—is that it threatens to infect us, and undermine our liberalising power, with the canker of imaginary guilt.

Now let me explain what is wrong with the three main assumptions of what I am calling the ‘cultural revolutionary decolonising story.’ These assumptions are: First, that Britain today is systemically racist; second, that this racism is rooted in British colonialism and its epitome, slavery; and third, that this racism manifested itself in a wholesale disparagement of the cultures of non-white peoples and the unwanted imposition of European culture upon them.

First, then, is Britain systemically racist? The issue is an empirical one and there are strong empirical reasons for doubting it. To begin with, there is the visible fact that in the recent Government of Boris Johnson, most of those in charge of the major departments of the British state were headed by Britons of Middle Eastern, Asian, or African heritage: Rishi Sunak, Chancellor; Priti Patel, Home Secretary; Sajid Javid, Health Secretary; Nadhim Zahawi, Education Secretary; and Kwasi Kwarteng, Business Secretary. Kemi Badenoch was then Minister of State for Equalities. If Britain really were systemically racist, that would not have happened—and especially, it would not have happened under a Conservative Government. Systemically racist countries do not fill the highest offices of state with members of ethnic minorities.

Next, the March 2021 report of the UK Government’s Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities—the so-called ‘Cred’ or ‘Sewell’ report—argued that contemporary Britain is not in fact systemically racist, even if it contains instances of structural racism. The report is controversial, of course, and has been angrily dismissed by left-wing journalists and activists, often by appeal to the ‘lived experience’ of ‘Black people.’ ‘Lived experience,’ however, is never pure and simple. Experience embodies perceptions, and perceptions can be mistaken. We cannot take ‘lived experience’ at face value.

But even where the ‘lived experience’ of non-white Britons is based on accurate perception, it represents the accurate perception only of some individuals. The Sewell Commission’s report, however, looks beyond the experience of particular individuals to broadly based social scientific data, so as to ground reliable generalisations. While I am not an expert on race in Britain, I do have expertise in judging the qualities of a piece of writing. I found the report conceptually careful, making cogent distinctions, disciplined by the empirical data, and nuanced in its judgements. In my view, it speaks with authority.

Besides, those ideologically inclined to dismiss Sewell should pay attention to the 2018 report of the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, Being Black in the EU. This found that the prevalence of racist harassment as perceived by people of African descent was lower in the UK than in any EU country except Malta, and the prevalence of overall racial discrimination was the lowest in the UK bar none.

So, for all those reasons, the first main assumption of the revolutionary ‘decolonising’ story is false. What about the second assumption, that such racism as persists in Britain today is rooted in British colonialism and its epitome, slavery?

A very large fly in the ointment of the argument that the essence of British colonialism lay in slavery and the racist contempt it embodied is that fact that the British Empire was the first major power in the history of the world to abolish the slave-trade and slavery in the name of a Christian conviction of the fundamental equality of all human races under God. In the last quarter of the 18th century, anti-slavery sentiment flourished widely among English Non-Conformists—especially the Quakers—and the Methodist or Evangelical wing of the Church of England. John Wesley, Anglican priest and founder of Methodism, prefaced his Thoughts upon Slavery (1774) with a quotation of the tenth verse of the fourth chapter of the Book of Genesis: “And the Lord said—What hast thou done? The voice of thy brother’s blood crieth unto me from the ground.” The context is Cain’s murder of his brother Abel and the implication is clear: African and Englishman, slave and master, are brothers, common children of the same God. This was the racially egalitarian view that triumphed in 1807 when the British parliament voted to abolish the trade in slaves throughout the Empire, and again in 1833, when it voted to abolish the institution of slavery altogether.

What is more, from 1807 and throughout the second half of its existence until the 1960s, the Empire was committed to suppressing the trade and the institution across the world—from Brazil, across Africa, to India and Malaysia. In the 1820s and ’30s, the Slave Trade Department was the largest unit in the Foreign Office. At one point in mid-century, the Royal Navy was deploying over 13% of its total manpower in suppressing the trade in slaves between West Africa and the Americas. According to the economic historian, David Eltis, the British spent almost as much suppressing the Atlantic trade in the forty-seven years from 1816-62 as they earned in profits over the same length of time leading up to 1807. And according to the American international relations scholars, Chaim Kaufmann and Robert Pape, Britain’s effort to suppress the Atlantic trade (alone) in 1807-67 was “the most expensive example [of costly international moral action] recorded in modern history.”

So, we cannot identify British colonialism with slavery and racism, because for the second half of its life—the one closest to us—anti-slavery, not slavery, was at the heart of British imperial policy. One mark of this discontinuity between the first and second halves of the British Empire’s life is the witness of African Americans in the 19th century. As the American historian of abolition, John Stauffer, wrote in his contribution to The Oxford Handbook of Slavery in the Americas:

Almost every United States black who travelled in the British Isles acknowledged the comparative dearth of racism there. Frederick Douglass [the famous black abolitionist] noted after arriving in England in 1845: ‘I saw in every man a recognition of my manhood, and an absence, a perfect absence, of everything like that disgusting hate with which we are pursued in [the United States].

Let me be clear. I am not arguing that the British Empire did not contain elements of ugly racist contempt for native peoples. It certainly did, but more at the colonial periphery than at the imperial centre, and more among settlers and planters than among colonial officials. Nonetheless, the worldwide suppression of slavery was a major policy of the imperial centre, which was sustained for a century-and-a-half and was premised on the principle of the fundamental human equality of all racial groups.

Now we arrive at the third and final assumption of the revolutionary ‘decolonising’ story, namely, that British colonial racism manifested itself in a wholesale disparagement of the cultures of non-white peoples and in the unwelcome imposition of ‘white’ culture upon them.

To begin with, let us just remember that human cultures are constantly in the business of learning and borrowing from one another. They don’t sit in racial silos, hermetically sealed against one another. For example, the religion that has done most to shape European culture—Christianity—wasn’t invented in Europe. It arose in the Middle East among a Semitic people who did not speak a Romance or Teutonic or Slavic language and whose skin-colour was not pink.

And when British and other missionaries brought a Europeanised version of that Semitic religion to Africa, they did not have the power to impose it. But they didn’t have to. As the historian Ronald Hyam has pointed out in his essay “The View from Below: The African Response to Missionaries” in the book Understanding the British Empire, Christianity, with its message of the ‘brotherhood of Man’ and ‘equality in Christ,’ proved naturally attractive to African refugees, slaves, children, marginalised adults such as women, and repressed teenagers such as girls fleeing compulsory circumcision.

Yet, if Africans adopted Christianity, they also adapted it. They did not swallow the European version wholesale and passively; they acted upon it and Africanised it. Famously, in Kenya, many African Christians refused to accept the European missionary prohibition on polygamy and so they set up their own independent, African churches.

Human cultures are constantly giving and taking, adopting and adapting. So, to divide the world into simplistic, static ‘white’ and ‘black’ cultural blocs is just not intelligent. Moreover, the idea that each culture has some natural moral monopoly in its own creations and that ‘cultural appropriation’ is a form of theft, is absurd. (If it were true, then anyone wearing trousers would owe the descendants of the ancient Gauls and Teutons compensation.)

Far from being contemptuous of the foreign cultures they found themselves in, British empire-builders were often fascinated by them. Take for example John Malcolm. Born in 1769 to a tenant farmer just east of my own native turf in south-west Scotland, Malcolm left home aged twelve with a parochial school education and travelled south. He did this because his father had gone bankrupt and could no longer afford to feed his seventeen children. Once in London, Malcolm joined the Madras Army of the East India Company and just over a year later—aged just 13—sailed eastward. While in India, he became fascinated by Persia, learned Persian or Farsi, led three diplomatic missions to the Shah of Persia, and wrote a History of Persia that Goethe is known to have borrowed three times from Weimar’s State Library and which is still—thanks to Cambridge University Press—in print.

Now, it is true that Malcolm’s interest in Persia was propelled by diplomatic—and in that sense, political—motives. And while not necessary, it is possible that he lived down to Edward Said’s post-colonialist stereotype of the British imperialist whose only motive for taking an interest in native cultures was to enhance British power. But if that was true of Malcolm, it was not universally true. As the historian of British India, David Gilmour, has written in his book The Ruling Caste: Imperial Lives in the Victorian Raj:

No serious survey of the scholars of the Indian Civil Service could conclude that they were a body of men who employed their skills to define an Indian ‘Other’ and create a body of knowledge for the purpose of furthering colonial rule … most were like the German orientalists, who had no colonialist agenda of their own, men motivated by pure curiosity and a desire to learn…. Some might even admire what they studied, the character of the Buddha, the vernacular literatures, the empires of Asoka and Akbar, the architecture of Agra … What imperialist use could be made of [John Faithfull] Fleet’s work on the inscriptions of the Gupta kings or [Evelyn] Howell’s translation of the Mahsud ballads or [Arthur Coke] Burnell’s catalogues of the Sanskrit manuscripts in the Palace of Tanjore? How, one wonders, are such works [as Said claims] ‘imbricated with political power’? [And] [h]ow do they fit in with … Said’s theory that ‘all academic knowledge about India … is somehow tinged and impressed with, violated by, the gross political fact’ of British domination?

If some Britons were keen to rescue Sanskritic culture, some Indians were just as keen to jettison it. In 1823, the Indian social reformer Raja Ram Mohan Roy wrote to Lord Amherst, the governor-general of India, to protest against the East India Company’s policy of supporting traditional Sanskrit learning, which he described as “the best calculated to keep this country in darkness.” Instead, he urged the British to promote the education of “the natives of India in mathematics, natural philosophy, chemistry, anatomy, and other useful sciences, which the nations of Europe have carried to a degree of perfection that has raised them above the inhabitants of other parts of the world.” Note: here it was the British who wanted to invest in classical indigenous Indian culture, while a progressive Indian dismissed it as benighted, urging instead that Indians be allowed to share in modern European enlightenment. (A decade later, Ram Mohan Roy travelled to England to lobby in favour of the East India Company’s banning sati, the Indian custom whereby widows burned themselves alive on the funeral pyres of their deceased husbands; in 1833, Roy died in what is now a suburb of Bristol, where he lies buried and where a statue, raised in 1997, now stands.)

Again, I am not saying that, in addition to elements of bona fide curiosity and admiration, the Empire did not contain elements of cultural repression, born of political fear or racist contempt. I think here of the repression of Gaelic culture in Ireland and the Scottish Highlands. Nonetheless, this needs to be distinguished—in a way that talk of cultural ‘genocide’ does not—from well-intentioned policies of native assimilation to British culture.

When the people of one culture meets another and dominates it overwhelmingly in number and power, only three outcomes are possible: either the dominant people annihilates the dominated one, or the latter adapts and assimilates, or the two peoples separate. Either annihilation or assimilation or separation. British colonial settlement did sometimes inadvertently cause the annihilation of a native people, as in the case of the Beothuk of Newfoundland. The third option, separation—of which Afrikaner apartheid or ‘separateness’ was a version—was never British imperial policy.

Whether in Canada, Australia, New Zealand, or South Africa, that policy was basically assimilation, even when provisional separation was countenanced. The egalitarian view that native people were essentially equal to Britons, possessed of the equal potential to develop economically and culturally, predominated in the imperial metropolis, even when some settlers on the colonial periphery doubted it.

Policies of assimilation usually involved such things as the creation of land-reserves, the provision of native schools, and the promotion of agriculture. The consignment of native Americans or Maori to reserves did involve provisional separation, of course, but only to shield them from being overwhelmed by too rapid change, while they learned to adapt. The goal of assimilation was the full integration of natives into European society as equal citizens. Accordingly, in South Africa’s Cape Colony black Africans were granted the vote on the same terms as whites as early as 1853—sixteen years before the Fifteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. In New Zealand all adult Maori males were granted the vote in 1867. And their native counterparts in Eastern Canada were granted it in 1885.

By its very nature cultural assimilation involves change. It involves letting go of at least some of the old and taking hold of at least some of the new. One of the benefits of imperial rule in Australia, New Zealand, and southern Africa was the ending of endemic inter-tribal warfare. The ending of persistent war is good, but it does entail the redundancy of warriors. Young aboriginal, Maori, and Bantu men had to learn a new way of life, because the old one was gone from them. And on the western prairies of Canada, the sudden collapse of the bison population in the 1880s meant that the economic basis for traditional native life vanished. Members of the ‘First Nations’ of Canada had to change, in order to survive, and they knew it. Which is why their chiefs insisted on the provision of schools when they were negotiating the so-called Numbered Treaties in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. And well into the 20th century they were lobbying for more residential schools—yes, the ones currently reviled in the press—where their children would be immersed in English language and learn a settled, agricultural way of life.

Now, the assimilation sufficient for survival and flourishing in the new future need not have involved the wholesale jettisoning of the past. It could have been discriminate; too often it was not. Some white teachers of native children were indiscriminately disparaging of their traditional culture to a racist extent. That was wrong and lamentable. But the main point still stands: the British Empire’s policies of assimilation were intended to rescue native people from a past that was irrecoverable, so that they might flourish in a future that was unavoidable. And that they might do so as equal citizens.

In sum, as I see it, the revolutionary ‘decolonising’ story is wrong in every one of its three main assumptions.

Britain today is not systemically racist. Indeed, it is one of the least racist countries in Europe.

Such racism as persists among us is not rooted in British colonialism, which spent the second half of its life committed itself to anti-slavery out of the Christian conviction of the basic human equality of all races.

And third, British imperialists were not generally inclined to rubbish the cultures of non-white peoples, and non-white peoples were not generally inclined to resent what the British brought them. Often, they welcomed it, even while they adapted what they adopted.

So, the revolutionary ‘decolonising’ story about Britain’s systemically racist present and its centrally racist colonial past is a false story, and it should not be allowed to corrode faith in Britain’s future and to infect British policy with imaginary guilt.

Nonetheless, despite the striking nakedness of the ‘decolonising’ emperor, British university managers are often intent upon imposing ‘decolonising’ policies and British academics are often ready to adopt them. According to a recent report from the think-tank, Civitas, over half of universities in the UK are officially committed to undertake some form of ‘decolonisation.’

Why that is so bears a lot of reflection. But my own experience tells me that the main cause comprises the political zeal of a few, riding on the back of the historical ignorance of the many and their terror of being thought ‘un-progressive’ in the eyes of their peers. Never over-estimate the moral courage of academics. They may be fiercely independently minded in the narrow fields of their scholarly expertise, but in general they are perfectly capable of behaving like sheep. (I can say that, since I am one.)

So, what should we do about it? Cambridge University’s acting vice-chancellor has given a lead, as did Oxford’s vice-chancellor, Louise Richardson, just over a year ago when she called for more “ideological diversity” in our universities. We have to take the risk of voicing our dissident doubts about ‘decolonisation’ and putting sceptical questions to it. And if any professor or university manager slaps you down, protest your right to question a set of views that baffles even the vice-chancellor of Cambridge. And if your own university authorities won’t support you, appeal to the Free Speech Union.

What’s more, within the next twelve months, when the Government’s bill on freedom of speech in higher education comes into force, universities and student unions will acquire a statutory duty to defend and promote academic freedom. And both students and professors will acquire the right to appeal against their own universities to the Office for Students, if they believe that their freedom to dissent from a set of dubious social scientific and historical views is not being upheld.

It’s vital that we take risks in asserting our legal right to doubt and interrogate the ‘decolonising’ story, because what is at stake is so very important. What is at stake is confidence in Britain as an important pillar of the West at a time when illiberal powers are baring their teeth.

And then remember Elie Kedourie’s words: “the canker of imaginary guilt even the greatest Power can ill withstand.” The guilt that cultural revolutionary ‘decolonisers’ would hoist upon us is largely imaginary. The ‘decolonising’ emperor is almost entirely naked. So, we need to stand up and say what we see.

This essay is based on the author’s 2022 Roger Scruton Memorial Lecture: Deconstructing Decolonisation. A version of this talk also appears in The Critic.