“The Last Sleep of Arthur in Avalon” (ca. 1881-1898), a 279 cm × 650 cm oil on canvas by Edward Burne-Jones (1833-1898), located in the Museo de Arte de Ponce, Ponce, Puerto Rico.

PHOTO: PUBLIC DOMAIN.

On January 30, 2022, the historian Geoffrey Ashe died, two months short of his 99th birthday. He was perhaps the greatest living popular historian dealing with the Arthurian legend, although he dealt with a great many other topics as well. I myself have been reading his work since my boyhood but had only been in direct contact with him since 2020. I had written an article about Glastonbury for the Catholic Herald in which I mistakenly lumped him in with various scholarly denizens of that enchanted place who held, shall we say, alternative religious views. Ashe sent me an extremely courteous letter in which he pointed out that he was and always had been Catholic, and was a great supporter of the return of the Benedictine monks to Glastonbury that year. Alas, his disappointment was as great as mine when earlier this year Bishop Declan Lang ordered the Benedictines to cease offering the Tridentine Mass, effectively banishing them; the Catholic Bishop of Clifton imitating Henry VIII in banishing monasticism from Glastonbury was quite the sight.

At any rate, this past September I was able to visit Glastonbury and meet Geoffrey and his charming American wife, Patricia, in their home at the foot of Glastonbury Tor. It was an enjoyable and wide-ranging conversation, and the one hour allotted in deference to his age quickly became two. It was delightful to chat with them; he mentioned that his great contribution to Hollywood was mentioning that Camelot was quite possibly Cadbury Castle in Somerset—and that is where the map in the film of that name places it.

Arthurian lore is filled with many strands, and every motif in it, from Excalibur to the Holy Grail raises far more questions than it answers. Enthusiasts of every description from strict Catholics to moon-worshipping Wiccans have worked over its material. Geoffrey had spent much of his life wrestling with it. Having written a book on the Grail myself, I must concur entirely with a judgement of his:

Take the tale of King Arthur, with which I have had a good deal to do. The romantic believes it literally, and is wrong. The iconoclast, having seen through the fiction, dismisses it… but is also wrong. The mythos arises out of something authentic in Britain’s past, and the patient appraisal that can lead towards this must take account of all the data – fantasy and fable included. The proper approach to legends like this is to take them seriously without taking them literally.

Geoffrey Ashe’s approach was very much in my mind the rest of that day as I climbed the Tor and visited the Chalice Well, St. Margaret’s Chapel, the revived Catholic Shrine of Our Lady of Glastonbury (from whence the Benedictines had just decamped), and the Abbey ruins themselves. That night I had a wonderful dinner at the “George and Pilgrims,” which has been serving visitors to the town since the Abbey was a going concern before Henry VIII. The following day I visited the Welsh shrine of St. Alban at the Oratory in Cardiff, and then Caerleon—also renowned for its Arthurian connexions, from the parish church to the Roman Amphitheatre that many identify with the Round Table.

Making these rounds, some words of Orson Welles regarding Falstaff would keep recurring to me:

I think there has always been an England, an older England, which was sweeter, purer, where the hay smelled better and the weather was always springtime and the daffodils blew in the gentle, warm breezes. You feel a nostalgia for it in Chaucer, and you feel it all through Shakespeare. And I think that he was profoundly against the modern age, as I am. I am against my modern age, he was against his…I think he was a typically English writer, arch-typically, the perfect English writer in that very thing, that preoccupation with that Camelot, which is the great English legend, you know.

But in truth, England and Wales are far from having a monopoly on Arthur and his knights. I myself have been to the forest of Broceliande in Brittany, where Merlin lies enchanted, and Austria’s shrine of Maria Lanzendorf, where Arthur is said to have visited. The best candidate for the Holy Grail is in the cathedral of Valencia, while the statue of King Arthur at Innsbruck’s Hofkirche is incredibly striking. The Normandy-Maine border area of France claims to be the site of many of the tales, as do certain regions in Spain. In pure literature, of course, the Arthurian legends went into every language in Europe; for example, the effect of Parzival in German has been enormous. Beyond that, in concert with those of Charlemagne and Godefroi de Bouillon, the tale of King Arthur had a gigantic effect on Chivalry, and as a result, a lingering one even to-day both on civilian etiquette and on the military virtues. As with Charlemagne and Godefroi, those two more historically based figures whose importance is not merely Franco-German-Italian or Belgian, Arthur is in reality not only a Welsh/Cornish/Breton or English folk hero but a Pan-European one. As with Charlemagne, who according to legend sleeps under Salzburg’s Untersberg to rise again when his people need him, so too with Arthur, the “Once and Future King.”

Of course, the very motif of the King asleep in the Mountain, ready to return to save his people—whichever people they are—when most needed, appears throughout Europe. From Fionn mac Cumhaill in Ireland and King Pelayo in Spain to Emperor Constantine XI in Constantinople, scores of epic heroes await the summons.

Now, all of this farrago of literature and folklore might be seen as unimportant in considerations of the here and now, of the actual political future of Europe. But this would be most unwise. On the one hand, these paladins are all—Arthur in the fore—powerful symbols. That power may be used in many ways. Hitler’s men appropriated to themselves a de-Christianised legendarium including both Arthur and Charlemagne (as well as a number of other such figures) and attempted to inculcate their elite SS cadets with a sort of Neopagan Chivalry in the Ordensburgen. Indeed, the more esoteric wing of National Socialism was riddled with various bizarre mythologies. In our time, both the ‘Rightward’—sometimes to the point of Neo-Fascist Neopagans—and the ‘Leftward’ Wiccans seek to purge these figures of their Christian content and assimilate their desiccated husks.

These attempts are historically false to Arthur, Charlemagne, and their kin, and empty these heroes of their real power, which comes from their stirring invocations of the true and valiant Christian spirit of their respective homelands. A perfect example of this usage was the relationship of the Stuarts with the figure of Arthur, as explained by Norman Murray Pittock:

Subsequently, it was to be “those who supported the Divine Right of Kings” who “upheld the historicity of Arthur;” whereas those who did not turned instead “to the laws and customs of the Anglo-Saxons.” Arthur remained a figure central to Stuart propaganda. Stuart iconography celebrated the habits and beliefs of the ancient Britons. In particular, the Royal Oak, still a central symbol of the dynasty, was closely related both to ideas about Celtic fertility ritual and about the King’s power as an agent of renewal: “The oak, the largest and strongest tree in the North, was venerated by the Celts as a symbol of the supreme power.” It was thus fitting that an oak should protect Charles II from the Cromwellian troops who wished to strip the sacred new Arthur of his status. The story confirmed the King’s mystical authority, and also his close friendship with nature. Long after 1688, the Stuart dynasty was to be closely linked with images of fertility. In literature, Arthurian images of the Stuarts persisted into the nineteenth century. This “Welsh messiah, the warrior who will come to overthrow the Saxons and Normans,” was an icon of the Stuarts’ claim to be Kings of all Britain, both ‘Political Hero’ and ‘National Messiah,’ in Arthurian mold. Arthur’s status as a legendary huntsman (“the figure of the Wild Huntsman is sometimes identified with Arthur”) was also significant. The Stuarts made much of hunting; it helped to confirm their heroic status as stewards of nature and the land.

What the modern scholar, born of an age reared on propaganda, struggles to grasp is that this symbolism, for both rulers and their adherents, was quite sincere.

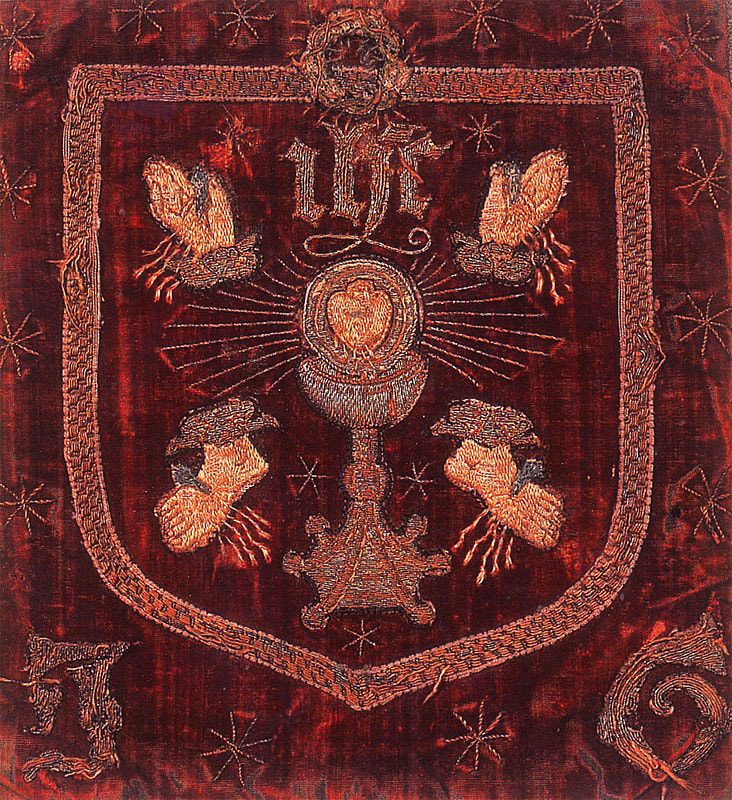

The most gripping element of the Arthurian Legend—a corpus filled to brimming with gripping elements—is undoubtedly the Holy Grail. This Sacred Vessel, containing Christ’s Blood, was intimately connected with all sorts of Catholic devotions: the Eucharist and the Passion, of course, but also the Five Wounds, the Precious Blood, and latterly the Sacred Heart. Just as the Arthurian Legend in toto would animate the Stuarts and their supporters, the Catholic opponents of Henry VIII took to the field under the banner of the Five Wounds during the Pilgrimage of Grace. The Sacred Heart would rally the Counter-Revolutionaries of the Vendee, the Tyrolians under Andreas Hofer, the Spanish Carlists, and the Papal Zouaves, to mention just a few groups who pitted themselves against Protestantism, Jacobinism, Liberalism, or whatever would-be avatar of “Modernity” appeared during their time.

Alas, for those who stand with Arthur and the Grail, it has been a long defeat—sometimes fast and dramatic, as in the two world wars and revolutions from the French to the Russian; sometimes long and debilitatingly slow, as with the transformation since the 1960s of Western Society into a madhouse dedicated to infanticide, sterility, and death. Nevertheless, as Geoffrey Ashe reminded us in his work, the ancient realities remain. Even as the star shone over Mordor, St. Michael’s Tower reigns over Glastonbury Tor. Despite the transformation of Glastonbury into a New Age fun fayre, the Abbey ruins continue to give their mute witness to the holiness of those who built and sustained the Faith there for so many centuries. Every Christmas, the Glastonbury Thorn—a remote descendant of the staff implanted at Wearyall Hill by St. Joseph of Arimathaea—blooms in the bleak midwinter, and a few blossoms are sent to the Queen. The abortive return of the monks to Glastonbury is surely a presage of the prophesied restoration of the Abbey by its last surviving member, Austin Ringwode (and quoted to me by Geoffrey in his letter): “The Abbey will one day be restored and rebuilt for the like worship which has ceased, and peace and plenty will for a long time abound.” And not in Glastonbury alone.

The Archduke Karl, Head of the House of Habsburg—itself the repository of so much of the religious and political traditions of Christendom—has urged resumption of “the struggle for the Soul of Europe.” He pointed out that “Europe was, as long as it was Christian.” The Arthurian legend, despite attempts to use it for other purposes, is a parable of a militant Catholicism that saved Western civilisation from the Turks and Tartars, and carried it and more importantly the Faith that built it across the globe. In that sense, all who love that Greater Europe, which really runs from San Francisco to Vladivostok, and from Cape Town to Narvik, may consider themselves among the vast company of the defenders of Camelot in every age.

As for Geoffrey Ashe, his work in this world is done. He died on January 30, 2022, having left behind a large and brilliant body of scholarship. But given his interests in Catholicism, Monasticism, and Britain, the date of his death is significant. It is the date of the judicial murder—for many, the martyrdom—of Charles I. In many ways, that King personified, as Stuarts tended to, the old traditions of England, Scotland, and Ireland. Vowing to God that if freed and restored he would return the Abbeys held by the Crown to the Church, his effort to reunite with Rome was one of the major charges at his trial. In the end, Charles I lost his life for rejecting the abolition of the Anglican Episcopate. Centuries later, on January 30 there passed Dom Prosper Gueranger, who restored both the Benedictine Order and Gregorian Chant to France after the French Revolution. Truly, a fit company for Geoffrey to join. So may we all!