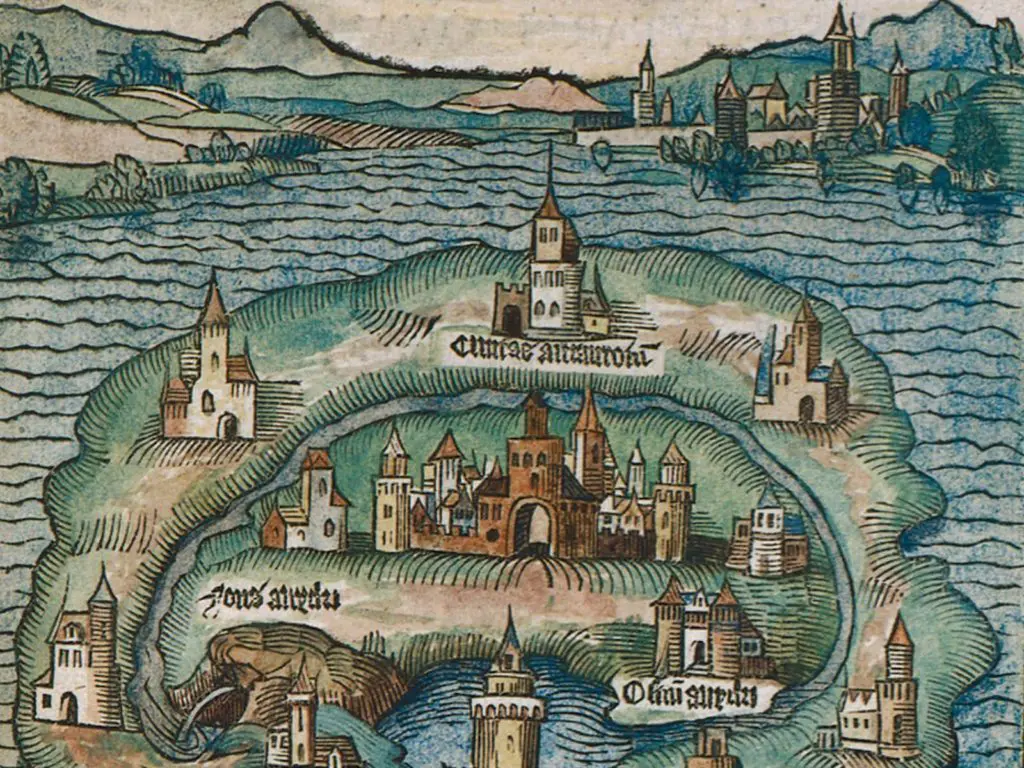

Colorized print of “Island of Utopia” (1516) woodcut by Ambrosius Holbein, from Thomas More’s Libellus veer aureus ned minus salutaris quam festivus de optima reipublicae statu, deque nova insula Utopia, Louvain, 1516.

Among the many dubious gifts of the Enlightenment is the concept of the utopia: the idealized state in which there is no war, no injustice, and stability goes hand in hand with tolerance. The word ‘utopia’ first flowed from the pen of statesman and martyr St. Thomas More, who coined the neologism from Greek elements meaning ‘no place.’ The word had lost its original ironic undercurrents by the early 1600s, and today many people—statesmen and scholars alike—use it sincerely to describe what they see as an achievable perfect society.

Enlightenment political philosophers from Immanuel Kant in his 1795 Perpetual Peace to Jean-Jacques Rousseau in The Social Contract believed that it was possible to raise society to a state of perfection—whether convinced through rational argument or dragged along kicking and screaming. Marx transformed the concept of utopia by weaving it into his quasi-religious theory of history, exchanging it for the Kingdom of God as the inevitable outcome of human history.

It is difficult to overstate the transformative effect of the idea of utopia on contemporary politics. Much, if not nearly all, diplomacy today passes through a utopian lens: if we could only get everything working properly, perpetual peace would be not only possible, but inevitable. The entire Western project of ‘democracy-building’ leverages NGOs, diplomatic pressure, and military force to spread the ideas—and ideologies—that progressives in the West believe will ensure the advent of this utopia.

But of course, there is a dark side to any attempt to force a utopia, especially one that is built on the shifting sands of progressive values. We see this dark side at work in the disaster that is Afghanistan, where failed democracy-building efforts left a void now filled by a violent, oppressive regime. We also see it at work in Europe, where a progressive EU threatens legal and economic coercion to punish member states like Poland and Hungary for their more traditional views.

Does this mean that nations ought not attempt to bring about peace and stability between their neighbours? Of course not. Problems arise not from ground-level efforts to create stability and solidarity but from top-down attempts to force ‘the end of history,’ ignoring the cyclical reality of political life.

There are few modern theories about the form of state and national governments that do not appeal to the classical concept of anacyclosis: the idea that every polis is subject to a cyclical, pendular evolution. According to the Greek thinkers Plato, Aristotle, and Polybius, who first attempted to classify the concept, there are three ‘benign’ forms of government—monarchy, aristocracy, and democracy—that inevitably decline into one of three ‘malignant’ forms—tyranny, oligarchy, and ochlocracy. The model of anacyclosis follows the arc of classical tragedy, in which the hamartia (the fatal flaw) is woven so tightly into the weft of the good that catastrophe is inevitable.

The model of anacyclosis influenced Western thought until the advent of utopian political theories in the Enlightenment. On a foray into the attic of our historical memory, we discovered, veiled in the philosophical dust raised by the Reformation movements of the 16th century, the source of the social tensions that affect us today. The most radical ideas derived from Reformation movements incubated in the 17th century only to germinate in the 18th, culminating in the French Revolution, the conventional starting point of the Contemporary Age.

From the Enlightenment onwards, utopian thinkers questioned the idea of the pendular cycle. In overturning the notion that the inevitable end of every benign regime is embedded within itself, they began to advocate for a revolutionary rupture from past political structures. For some, that rupture took the form of ‘scientific inevitability;’ for others, it was an ineluctable ethical imperative. Thomas Malthus, for example, the ideological grandfather of Darwin and Marx, foretold the eschatological end of humanity as a consequence of the depletion of natural resources. Others, like Marcus Tullius Cicero, Niccolò Machiavelli, and Giambattista Vico, acknowledged the inevitability built into the classical model but began to think about the best way to delay the degenerative processes of the political system, seeking to mitigate its debasement and corruption.

After the French Revolution, aristocracy, corroded by centuries of injustice and tainted by the emerging bourgeoisie’s ‘enlightened despotism,’ gave way to democracy—but not a democracy that saw itself as part of the great cycle. Modern democracies strive to free themselves from anacyclosis and to inoculate themselves against the tragic collapse the ancients believed to be inevitable. In almost every case, this inoculation against political degeneration began with the introduction of control and accountability mechanisms. Rulers spelled out the rules of political engagement in constitutions that, unfortunately, were often dense and open to various interpretations. Parliaments and congresses emerged as interpreters of the ‘popular will’ to limit unbridled or arbitrary exercise of power. However, in many cases, they wound up instead legitimising social inequality, camouflaging their intrinsic oligarchic nature.

On paper, everything looked fine, but the inherent complexity of human nature had not changed. The liberal revolution of the 19th century, which purported to champion the interests of individuals and the nation-state, was in fact more concerned with promoting the rise of the wealthy bourgeois classes who had taken the place of the deposed aristocracy. Just like in ancient Athens, the call to democracy soon became a mere mask disguising an ‘enlightened’ oligarchy that patronisingly assumed it alone could properly interpret the wishes of the people—even to the point of oppressing the people ‘for their own good,’ as when King Pedro IV, the figurehead of the liberal sectors of Portuguese society, warned his ‘people’: “We have come to set you free! Help us, or we will be compelled to release you by force!”

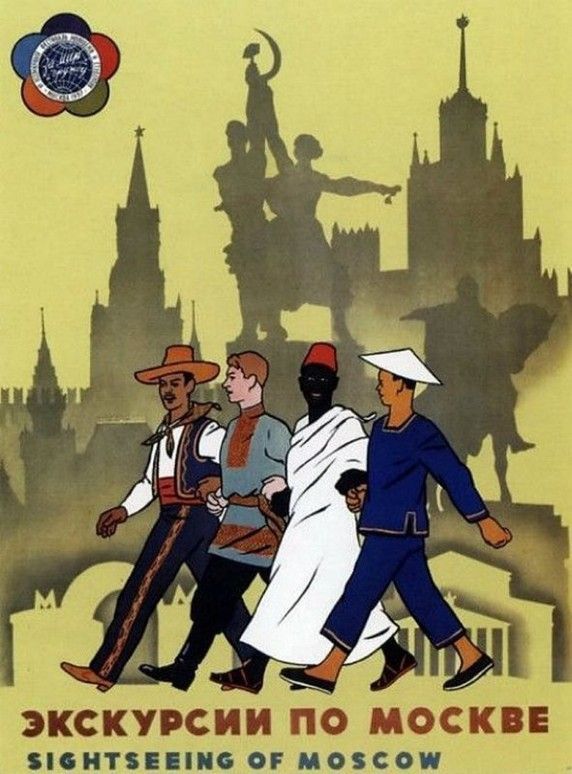

With the growth of disruptive revolutionary ideas, power in the West began to fall into the hands of an often idealised Fourth Estate, precipitating ochlocracy as the government constantly responded to—and tried to manage—the force of the mob. As Georges Sorel theorized, the threat of wrecking-ball violence led to the emergence of powerful political currents of social disruption; governments scrambled to appease the mob and defuse the imminent explosion. This gave rise to the hyperbolic socialist ideas that eventually led to communism and later, in reaction, fascism. The terrible lesson we learn from these regimes is that revolutionary utopias at the beck and call of the mob degenerate into awful and bloody totalitarian dystopias.

After World War II and during the Cold War, democracy reasserted itself as the regime of preference. However, given the complexity of social processes, there is to this day still no consensus on how to define democracy. It has become a buzzword that contains everything and its opposite, that can be invoked by anyone in defence of anything. Even indisputably totalitarian regimes do not hesitate to call themselves democracies, often pleonastically described as ‘popular.’ Today, the most widespread definition of the concept is perhaps the one given by Karl Popper, who found himself able only to state what democracy should not be. Ultimately, the label ‘democracy,’ used at the discretion of political players and the media, has come to demarcate the boundary between the ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ sides of history.

The sudden fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the Soviet Empire shocked the world. Many people became convinced that a new long-term era of progress and prosperity would finally be possible in the peace brought about by the end of the ideological polarization between the Soviet Union and the West. But of course, the totalitarian revolutionary drive persevered. Disdaining all scientific evidence, the offshoots of the felled communist tree continued to cling to Rousseau’s misleading narrative of the nature of man, the morally disruptive ideas of Sade, and the class struggle model championed by Marx.

Communists benefited from a double standard applied in the wake of WWII, as allied propaganda downplayed communist atrocities since Russia had fought with them on the winning side. This contributed to a significant intellectual and political leniency towards communism that, despite the rigors of McCarthyism in America and strong anti-Russia sentiment in Western Europe, is still on the rise today. Our increasingly materialistic Western societies take freedom for granted and see communist revolutionary views as an idealistic and justifiable response to reactionary forces. As such communism often ends up on the ‘good side’ of the historical ledger.

The narrative about the last Spanish Civil War, for instance, is almost entirely one of class conflict: a war of rich against poor, bosses against workers, landlords against peasants, backwardness against progress, and the cold strength of steel against passionate, romantic idealism. One side is always painted as a plausible utopia, the other as a deplorable dystopia. This flimsy analysis provokes a cynical double standard in categorising the victims of that conflict. The demise of some is seen as perfectly acceptable: as heirs of centuries of injustice and social predominance, they deserve to be thrown into the trash can of history. In contrast, others are depicted as innocent idealists sacrificed by sinister executioners defending unfair privilege and obscurantism.

This kind of inadequate analysis is universal today. Oversimplifications of Marxism have thrived in the West since the fall of the Soviet Union amid growing materialism and moral relativism. Fuelled by rampant ignorance and fostered by a chaotic education system, Marxism now controls the language—and thoughts—of the West. The overwhelming power of a media controlled by monopolistic mega-capital increasingly manipulates minds and wills, imposing a specific lexicon that conditions social, cultural, economic, and political behaviour. In other words, even in our democratic regimes, the behaviour of our citizens is so closely controlled that true freedom—and even the language to speak of freedom—is a vanishing dream.

It was essential that the Democratic regime control language and its lexicon. Fair-play behaviour has long been abandoned in contemporary use of language and thought. Understanding the role of language as a critical instrument in the implantation of totalitarian thinking had been a concern of many thinkers, such as Hannah Arendt, Raymond Aron, and, in his later years, George Orwell. Orwell was aware of language’s almost hypnotic role in society, how words take over our passive or subconscious thoughts. His 1984 explores the societal implications of Newspeak, an invented language of simplified grammar and restricted vocabulary designed to limit ability to think and express potentially ‘subversive’ concepts such as personal identity, self-expression, and free will. For Orwell, the ultimate result of manipulating words is the impoverishment of language, i.e., of communication, and the consequent loss of critical capacity.

As it turns out, a kind of Orwellian Newspeak has become the democratic 21st century’s standard political and cultural language. Yet, beyond reading Orwell as a prophet, we should read 1984 as a profound satire on the thought-manipulation foisted on humanity since the 1930s. Even in Orwell’s dystopia, the attempt to destroy the critical capacity of the human mind always faces resistance.

In the book as in real life, this resistance against an increasingly intolerable status quo finds itself vilified and discredited. In the West those who feel marginalised within their own cultures are disparagingly dubbed ‘populists.’ One of the main characteristics of this so-called populism is an attempt to short-circuit the oligarchies that own the system. Above all, these ‘populists’ contest the enlightened neo-despotism of unelected agents who control the power and disguised in democratic theatrics, decide the fate of their citizens with no due mandate to do so.

In the age of cyber-globalism, ‘democracy’ has become a marketing buzzword, expedient branding taken from the authorised lexicon of political correctness. Gone is the essence of the people’s freedom-based sovereignty: the right to tolerant and plural expression; the acknowledgment and incorporation of minority views; the recognition of human dignity without discrimination against age, race, social class, sex, or political ideas. As long as we avoid the question of what democracy is and focus only on fallacious issues of form or content, we will be kept utterly hostage to political relativism and demagoguery.

The truth is that the political initiatives of democracy-building combine Schmittian ‘friend-foe’ dualism with Machiavellian ‘strong-weak’ relativism. This is why instead of spreading democracy where it is most needed (like China, Vietnam, North Korea, Venezuela, or Cuba), the Western powers have chosen to promote sudden and violent change in Africa and the Middle East. We need look no further than Afghanistan to see the failure of this approach. What hidden economic or ideological agenda led to the interventionism of the Bush and Obama-Clinton administrations, supported by their European henchmen? What excuses the clumsy, almost criminal, approach of the twenty-year intervention in Afghanistan? Have the ‘liberated’ peoples become better, happier, supported by more democratic institutions? Has Islamic totalitarianism been confronted? Or, on the contrary, has it been empowered?

Was it worth sacrificing millions of human beings—lives and property destroyed forever, entire communities pushed to the brink of extinction—as in Syria and Iraq? What kind of democracy-building do we expect to see from populations constantly torn apart by foreign wars, societies in which those most inclined towards and receptive to Western-inspired processes—the Christians—have been practically annihilated? But the elites behind global capital and the constellations of NGOs that benefit from that capital are likely satisfied with such lucrative results.

Does this criticism of recent exploits show contempt for the procedures and purposes of democracy-building? Not at all. On the contrary, all initiatives on the ground that might promote or strengthen a sturdy civil society are commendable. However, the only way to bring a national society out of a state of dependence on the whims of an elite-controlled mob is through a stable, enduring, and comprehensive educational system that is immune to political whims. Only then can democratic civic participation contribute to the elevation of the polis.

Creating this educational system, of course, demands transparent and honest electoral processes and a culture of justice and authority at the service of all equally. It also requires balanced governance that combines subsidiarity with solidarity; in other words, nations must be democracies in practice, not merely in name.

Conservatives, of course, are aware of the urgent need to reduce the bureaucratic machine to a minimum. But in the quest to devolve governance to the local level, we must not forget the existential dignity of the penniless castaways generated by the oligarchic system. Our faux-democracies have for decades cultivated a sense of dependence that will take further decades to unlearn—and in the meantime, we must develop social structures to support citizens just now learning what it means to be free.