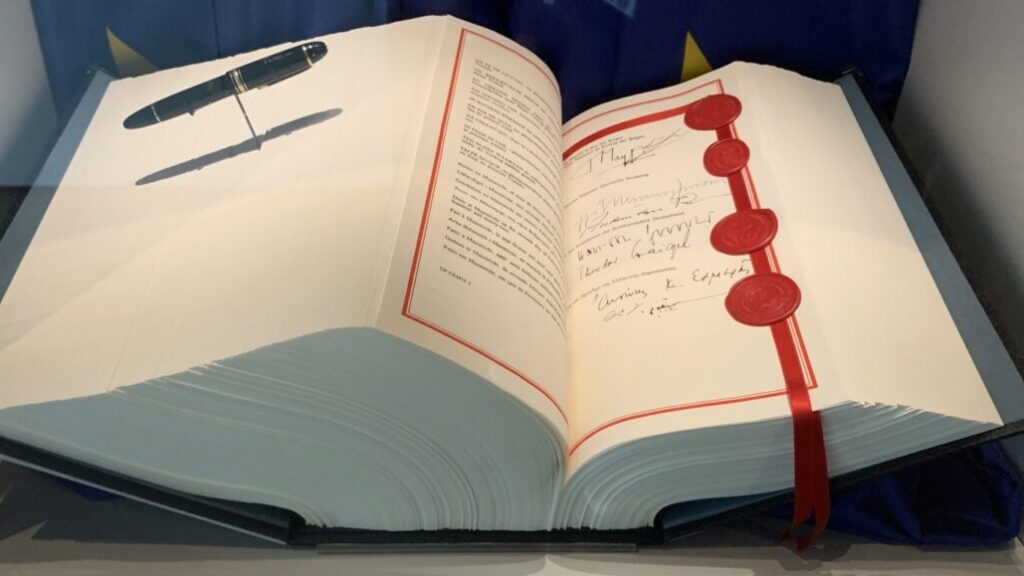

The Treaty of Maastricht shown at an exhibition in Regensburg. The book is opened at a page containing the signatures and seals of the ministers representing the heads of state of Belgium, Denmark, Germany, and Greece.

Photo by Mateus2019 , CC BY 2.0 de, via Wikimedia Commons.

Attempting to expound someone else’s thought is always a high-risk endeavor. But since I recently declared Dalmacio Negro Pavón the most significant political thinker in Spain in recent decades, with all due caution, I will outline what I consider to be some of the interpretive keys to Negro Pavón’s thought.

The work of Dalmacio Negro Pavón reveals that politics cannot be understood without anthropology: the various conceptions of humanity throughout history are not mere theories but paradigms that have shaped the lives of peoples and conditioned political thought.

Post-World War II Europe has always been defined by people, projects, and geopolitics. On this basis, there have been periods of great prosperity and periods of fruitless blossoms in Europe. European prosperity has always been determined by the presence of leaders with strong character and ambitious vision, as well as by geopolitics conditions. Periods of decline, on the other hand, tend to flow from weak leadership, a lack of vision, and tense geopolitical relations or crises of an international scale.

After the war, Europe was in need of a fresh start, in order to restore trust between countries torn apart by war. Germany was in ruins and under four-power occupation, and with the help of America and France, it was necessary to rebuild the free German territories. Schuman, Monnet, De Gasperi, Spaak, and all the European leaders of the time, were in agreement on the need to start freshe:thus the personal conditions were set for the launch of the European project. The geopolitical situation also made it necessary for the free Western countries to unite in order to block the expansionist ambitions and communist ideology of the Soviet Union.

In the second half of the 1950s, Charles de Gaulle and Konrad Adenauer realised that it was the cooperation between France and Germany that would determine the fate of the free part of Europe. The relationship of trust between the two statesmen was the basis for the Élysée Treaty of 1963, which provided a framework for cooperation between the two countries. The six countries that were part of the European integration process, namely France, Germany, Belgium, Italy, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands. developed a close relationship and sought to join forces politically, economically, and culturally. In geopolitical terms, de Gaulle sought to strengthen the sovereignty and independence of Europe from the U.S., and his vision for Europe was that only a federation of independent states “from the Atlantic to the Urals” could give Europe a worthy place among the world powers.

As the 20th century progressed, the construction and fortification of the European Union continued to depend upon alliances between leaders of string character from among the European nations. In the late 1970s and early ’80s, the friendship between French President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing and German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt would be a powerful force in the creation of modern Europe. Their cooperation led to a number of achievements on the European stage, from the creation of a European monetary system to the introduction of a new currency unit, which made independence from the U.S. dollar possible. They established the European Council, which allowed European heads of state and government to meet regularly, thus emphasising the leading role of the member states. Giscard d’’Estaing’s successor, President François Mitterrand, continued the legacy of cooperation with Germany, whose chancellor at the time was again Helmut Kohl. Despite being two statesmen from different political families, the two politicians worked together smoothly. Mitterrand accepted, albeit reluctantly, the reunification of Germany, and Kohl accepted the introduction of the euro, allaying fears of the dominance of the German mark.

Geopolitical factors also continued to affect the formation of the EU late into the 20th century. Regime changes in post-Soviet Central Europe and the accession of Austria, Finland, and Sweden to the European Union were hopeful signs that it was possible to dream big on the European stage and to create a political union that went beyond mere economic cooperation. It was a moment of historic opportunity for Europe: a chance to regain the self-determination it had lost and to shape its destiny more independently of the other great powers of the world. Thus, thirty years ago, the Maastricht Treaty was signed, and the modern-day E.U. was officially established. But its ambitions, as it later turned out, were perhaps exaggerated. The reasons for this can be traced back to several factors.

Among the personal factors, the Franco-German tandem after Mitterrand and Kohl no longer exhibited the strength, unity, and character of the previous decades. The cooperation between Jacques Chirac and Gerhard Schröder had more of a theatrical element and less of the deep concern for the future of Europe that had prevailed in the case of their predecessors. Angela Merkel took over as Chancellor in 2005 and has been a major player in European politics for more than fifteen years. However, Merkel never found a truly strong partner in France, where there was a very weak Chirac in his last years as president, followed by Nicolas Sarkozy, who had internal problems and only served one term, and then the very unpopular Francois Hollande. France thus failed to play a decisive role on the European stage. Ironically, Emmanuel Macron, whose vision for Europe echoes that of Charles de Gaulle, now has to work with a German Chancellor, Olaf Scholz, whose reputation is not even secure in his own country.

For the aspirations of the Maastricht Treaty to become a reality, Europe would need to cultivate a climate of mutual trust and consensus among the various member states. This is what the Franco-German cooperation has benefited from for decades and why it was able to deliver a result. But the last twenty years have seen a change in this respect. The Visegrád countries of Central Europe have a strong independent voice in the EU decision-making mechanism, and new and different views are making their way in Europe. This in itself casts doubt on whether the Franco-German axis can maintain its position as the sole guiding force in Europe.

There is a growing ideological divide between those who want to see a federal Europe and those who wish European cooperation to elevate the independence of the individual member states within the union. On the other hand, since the early 2000s, a series of events such as the financial crisis following the collapse of Lehman Brothers, the Greek financial crisis, Brexit, the migration crisis, COVID-19, and, more recently, war, have shaken the wheels of European integration. Not only this, but the economic competitiveness of European countries, and therefore the competitiveness of the entire continent, is deteriorating day by day.

The leaders of the European nations need to engage in some introspection. The weight of the Franco-German tandem in this ever-expanding integration will always remain, but it can only be successful if it is based on the pursuit of consensus. Leaders with character and vision will be key to ensuring that the European institutions do not become institutions without control and with unlimited power, which would steer European cooperation astray or into a dead end.

Finally, the vision of the countries of Central Europe must be allowed to play an important role in the future of Europe, in accord with the principle of equality among the member states and because of the diversity and pluralism of Europe. Moreover, because of their peculiar historical experience under Soviet rule, these people and leaders of these countries have important wisdom to contribute to European governance. The leaders of Europe must avoid any rigid dogmatism that might preclude the unique experience and vision of the individual member states from playing a role. Ever closer union, in the sense of rigid conformism, is not the cure for all diseases. Europe’s ship must be steered through rough seas, and for that, we need leaders with character who will rise up to take responsibility for their own countries.

This is an edited version of the author’s speech delivered at the Subotica City Hall, 18 March 2023.