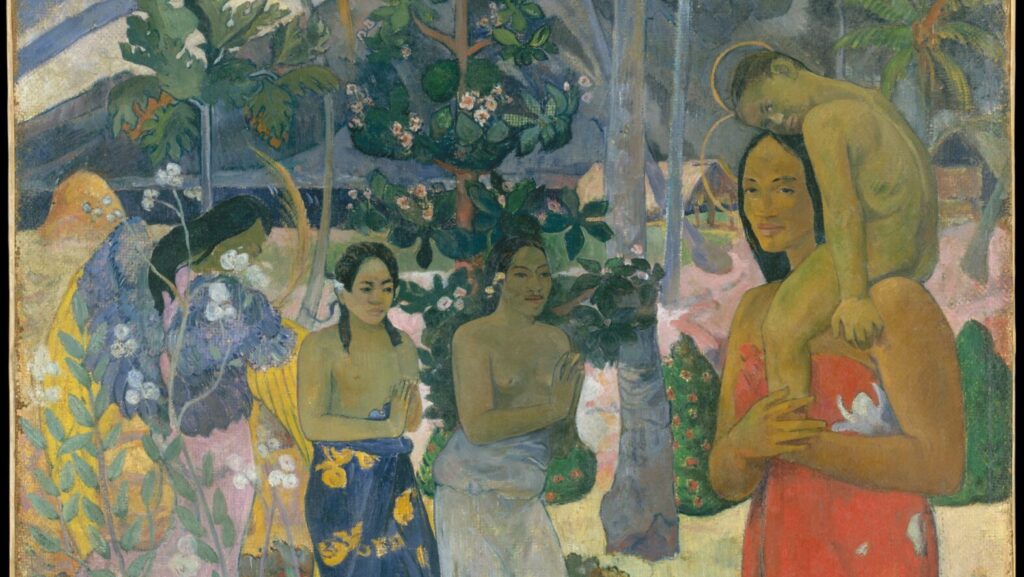

Ia Orana Maria (Hail Mary) (1891), a 113.7 x 87.6 cm oil on canvas by Paul Gauguin (1848-1903), located in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Gauguin devoted canvas to a Christian theme. If Belloc’s idea, that “the Faith is Europe, and Europe is the Faith” is taken seriously, then Europe extends even to such far-flung Pacific isles like Tahiti.

More than any other continent or culture in the world today, Europe is now deeply weighed down with guilt for its past. Alongside this outgoing version of self-distrust runs a more introverted version of the same guilt. For there is also the problem in Europe of an existential tiredness and a feeling that perhaps for Europe the story has run out and a new story must be allowed to begin.

– Douglas Murray, The Strange Death of Europe: Immigration, Identity, Islam (2017)

Defining Europe has always been a bit difficult, and never more than now. ‘Definition’ here has two meanings: what Europe is, and what its geographical boundaries are. Before we can tackle the second question, however, we must try to answer the first. At one time in this writer’s lifetime, it was delineated as the pre-1989 European Union. For De Gaulle, it stretched from the Atlantic to the Urals. Novalis, in his famous essay, contrasted Europe with Christendom. But we’ll look first at Hilaire Belloc’s idea, that “the Faith is Europe, and Europe is the Faith.”

These closing words of his book, Europe and the Faith, were attacked by non-Catholics from the moment they were published, and by very many Catholics since Vatican II. The former assaults were directed against today’s Catholic Church—or at least the Catholic Church of Belloc’s day. To the Eastern Orthodox among these, and despite the Schism of 1462, sociologically speaking, what one may say of Catholic countries is usually true in Orthodox ones as well. The Spanish and Italian countryside have much in common—in terms of folk customs and the like—with those of Greece and Romania. Schism aside, the doctrinal similarities have produced similar cultures. By the same token, it is not just that the Protestant nations of Europe have Catholic pasts; rather, the current or former state churches occupy roughly the same role that the Catholic Church did before the 16th century—a role which the Catholic Church itself has lost in most historically Catholic countries, due to subsequent revolutions.

Catholic critics of Belloc’s idea will complain that it smacks of the phantom crime of ‘Triumphalism,’ that strange product of the ’60s clerical imagination. But in context, that quote is anything but:

In such a crux there remains the historical truth: that this our European structure, built upon the noble foundations of classical antiquity, was formed through, exists by, is consonant to, and will stand only in the mold of, the Catholic Church.

Europe will return to the Faith, or she will perish.

The Faith is Europe. And Europe is the Faith (my emphasis added).

Rather than a boast, Belloc’s line is a stark warning. But in any case, Europe is the mostly secularised husk of that Res publica Christiana, that Abendland, that Occident, that Holy Empire, of which Constantine the Great was the founder, Charlemagne was father, and St. Columban the first native; that entity whose first charter was Theodosius the Great’s Edict of Thessalonica, that made Baptism entry into citizenship as well as membership in the Church. It is the merging of the Roman Empire with the Germanic, Slavic, and other peoples who entered into the cultural and religious orbit of that Empire, transforming it and being transformed.

With that understanding, Europe was from the beginning more than the Continent that bears that name. At its inception, the frontiers included what is now Turkey, Armenia, Georgia, Syria, Lebanon, the Holy Land, and North Africa—even Ethiopia, and Iraq to some degree. The rise of militant Arianism tore most of those lands away in the 7th and 8th centuries and besieged the others. Indeed, they may well be seen as a sort of Europa Irredenta, with the Islamic Conquest, the Crusades, and the British, French, and Italian struggles in North Africa all being part of the same struggle between the Cross and the Crescent as the frontier went back and forth. Seen in this light, France’s 1962 defeat in the Algerian War might be seen as a defeat for all of Europe, but at least whole villages of Icelanders and Irish are not being kidnapped and sold as slaves, as was the wont of the Barbary Pirates two and three centuries ago. We may say that the Continent itself represents the First Circle of Europe, with a shifting and uncertain southern border.

But European boundaries are really set much further abroad. The 16th and 17th centuries saw Europe convulsed by the Protestant revolt on the one hand and expanding—via Spanish, Portuguese, French, Dutch, Swedish, and Danish ships on the one hand (including the African slaves they bought from the petty Kings of the Guinea Coast and used for cheap labour), and Russian Cossacks on horseback advancing over Siberia to the Pacific Ocean on the other. Over the next several hundred years, fighting the natives and each other, they planted their flags and their versions of the Cross from pole to pole. Thus, it was that Russia extended finally to Alaska and Northern California, and the settler countries of the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Argentina, Chile, and Brazil came to be. So much of the Spanish expansion came under the aegis of that country’s branch of the Habsburgs that the Double Eagle may still be seen on churches and public buildings from Texas to Chile.

Regardless of their political relations with their respective mother countries, the settler countries attracted a large number of European emigrants from countries other than their own metropoles through the 19th and early 20th centuries. These were folk who for religious, political, or economic reasons left their homelands, thinking they knew better (whether rightly or wrongly) than those under whose rule they had lived. In leaving their homelands, they showed as much of a pioneering spirit as the original colonists, who crossed the seas more or less unaware of what awaited them. When these two groups came together, they had the makings of a population that was very resilient, if often irreverent.

In time, as Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi rightly predicted after World War I, two of the frontier nations—the United States, and the newly-Communist Russia—would eventually divide the Continent between them. Despite the end of the Soviet Bloc and the creation and expansion of the European Union to the borders of the former Soviet Union (and beyond, if one includes the Baltic States, although their incorporation into the USSR was never recognised by the U.S.), the Americans remain culturally dominant in Europe; and, as the fighting in and about Ukraine shows, the Russians have not vanished either. Europe’s two most powerful daughters have offered their Mother Continent two visions: that of George Soros, and that of Vladimir Putin. Neither, perhaps, is particularly appealing, if for very different reasons.

Nevertheless, despite being an American, I will assert, as I have many times before, that we Americans are in reality Europeans. Moreover, it is not merely we and the Russians who remain European, but the aforementioned Canadians, Australians, Argentines, and so on. Otto von Habsburg wisely wrote that Europe in reality stretches from San Francisco to Vladivostok. This we can consider the Second Circle of Europe. The Italian Identita Europea Cultural Association has a manifesto that I entirely endorse. Its last paragraph is telling:

By encouraging an EUROPEAN IDENTITY we do not intend to promote a ‘western culture’ which absorbs and dissolves all diversities in a leveling attempt. On the contrary, our aim is to enlarge this identity beyond the European boundaries, thus recovering that large part of our continent ‘outside Europe’—from Argentina to Canada and from South Africa to Australia—which looks at the old continent not as a distant ancestor but as a real homeland.

It is this idea of Europe as our common homeland that we colonists need to cultivate. Europeans often look at us as rude, boorish, and ignorant; and we, in turn, all too often look at the Mother Continent as weak, effete, and indeed, deservedly spent. While it is the case that both views have some truth to them, they are far from all there is to the question. Europe remains a storehouse of culture, religion, and lived wisdom acquired over many generations. But in today’s climate when pride in being a European—or a native of any of its constituent countries—is called ‘Fascism’ (or worse) by a truly effete establishment, then opposition to that establishment is hamstrung by fear. A dose of colonial energy and drive could definitely come in handy in maintaining and regaining Europe’s sanity, for all that America’s stability is similarly under siege.

We Americans, and the rest of the settlers, need to see that all of our histories and their various dynamics really do have their roots in Europe and the various conflicts there. Russia, of course, has oscillated between Slavophiles who wished to retreat into their national identity and Westernisers who wanted to shed it entirely. It might be observed that such diverse figures as Tsars Paul and Alexander I and the philosopher Vladimir Solovyov saw what was right and wrong with both positions: hoping to bring the best of the Russian ethos to the service of the common European home, and vice versa. Latin American Conservatism has its roots in the Royalist side during their wars of independence, and afterwards was that element that continued to look to Europe and Catholicism for inspiration, while their opponents looked to (and were often funded by) the United States.

Canadian Conservatism’s Anglo expression was inspired partly by the Jacobite Scots, and much more by the Loyalists who fought and fled the American Revolution; their French equivalent opposed the revolution in the Mother Country, and latterly became very Ultramontane in Catholic politics. In the United States, we call Socialists ‘Liberals’ and Liberals ‘Conservatives,’ because for the most part our Conservatives left after the revolution and ceased to be an organised force. Australia and New Zealand, due to their unique histories, never developed Conservative parties as such, although they did deliver groups called ‘National’ who approximated it to some degree. In South Africa, the racial issue and the struggle between British and Afrikaners led to a situation where republicanism, Calvinism, and Apartheid opposed Monarchism, Roman and Anglo-Catholicism, and racial integration; the former triumphed initially, but that forty year-long triumph ushered in the current mess. So it goes through the rest of the settler countries.

It might be objected that there are many areas that may have European-derived institutions, religion, culture, and language, but little in the way of DNA. Obvious examples of such places are much of Latin America and the Caribbean; the Philippines; Mauritius, Reunion, and Seychelles; Portuguese-speaking Africa; and even parts of the American South and some of our urban ghettoes. Many who consider themselves—or who are considered by the media, government, and other such riff-raff—as ‘right-wing,’ while admitting the European nature of the settler countries, would draw the line at these places.

I would answer with Jean Raspail, and quote his character Hamadura, in Camp of the Saints, an ex-deputy to the French Parliament from Pondicherry, India: “To my way of thinking, being white isn’t really a question of colour. It’s a whole mental outlook.” Obviously, ‘white’ here is a codeword for ‘European.’ It is these countries that I would maintain comprise the Third Circle of Europe and, moreover, includes places like Goa and Mangalore, India; Ambon, Timor, and Manado, Indonesia; St. Louis, Senegal; Malacca, Malaysia; and Singapore, Hong Kong, and a great many other places. Moreover, it encompasses the many peoples created by the encounter between Europe and the rest of the World, such as the Anglo-Indians and the Eurasians.

Where then, does the Fourth Circle of Europe lie? The political, ethnic, cultural, linguistic, and geographical contours of Europe have changed immeasurably since the Christian-European entity was legally constituted back in 380. But Baptism remains with us as an entry. By that standard, many Catholic and Anglican Bishops from the Third World are more European than a good many of their confreres in Europe and America; the same goes for the clergy and laity. To abandon the Faith that made Europe—that is Europe—is to abandon Europe herself and to embrace barbarism. The Fourth Circle is in fact the boundary of the Kingdom of Christ, which is as hard to map accurately as it was when Theodosius signed his edict. As Ernest Oldmeadow wrote in 1926:

Christ the King has other rebels besides Russia and Mexico and France. The map of His dominions shows not only the Empires and Kingdoms and Republics, but also the counties, the towns, the villages, the hamlets, and—like the ordnance maps of largest scale—the homesteads each and all. Indeed, it goes farther than the work of any human cartographer; because it shows the inmost places of every human heart. Even the humblest man or woman or child alive is, so to speak, a tiny province in the dominions of Christ the King: a province either submissive or disobedient, either loyal or rebellious.

That Fourth Circle runs through each of us; the border between the light and beauty of Christ’s Holy Empire on the one side, of the border, and the horror and disgusting pettiness of Satan’s realm of Chaos on the other. Most of us cannot live on the right side of that iron curtain, given the circumstances we must live under; but we can pray and work so that the situation changes, and so that, in any case we and ours die on the side of Christ and His saints.