There is a certain joy to watching an excellent teacher speak to a group of people. Seeing the sheer diversity of gifted teachers is very helpful to anyone who wishes to spend much of their time communicating and mentoring. I have had the chance to watch more than my fair share of talented teachers ply their trade, and it was while watching one such teacher that I was inspired (or perhaps guilted) finally to read Charles Dicken’s A Christmas Carol.

I was part of a seminar made up largely of graduate students and future graduate students (almost all of whom conservatives) led by Robert P. George, McCormick Professor of Jurisprudence at Princeton University. While speaking, he illustrated a point of ethics by referencing Mr. Fezziwig. Professor George was greeted mainly with blank stares. “Don’t you all know Mr. Fezziwig?” he asked. All but two students indicated that they did not. Professor George looked at the two students who seemed to know what he was talking about and said, “Can you tell them who Mr. Fezziwig is?”

“Isn’t he from A Christmas Carol?”

“Yes!” Professor George said excitedly, before regaling us with an explanation of Mr. Fezziwig’s character, the contrast he provides to Scrooge, and the central role of his character to the broader point of the novella. “This is why you all have to read Dickens’ original! Mr. Fezziwig has been cut from most adaptations, and so few people today read Dickens’ version that they miss out an important part of the story!”

Professor George was right. Despite the fact that the outline of A Christmas Carol is extremely familiar to most people today, many have never read the work. With the celebration of Christ’s birth approaching, it is the perfect time to approach Dickens’ classic, a book that encapsulates much of what makes Christmas Christmas—and Christianity Christianity.

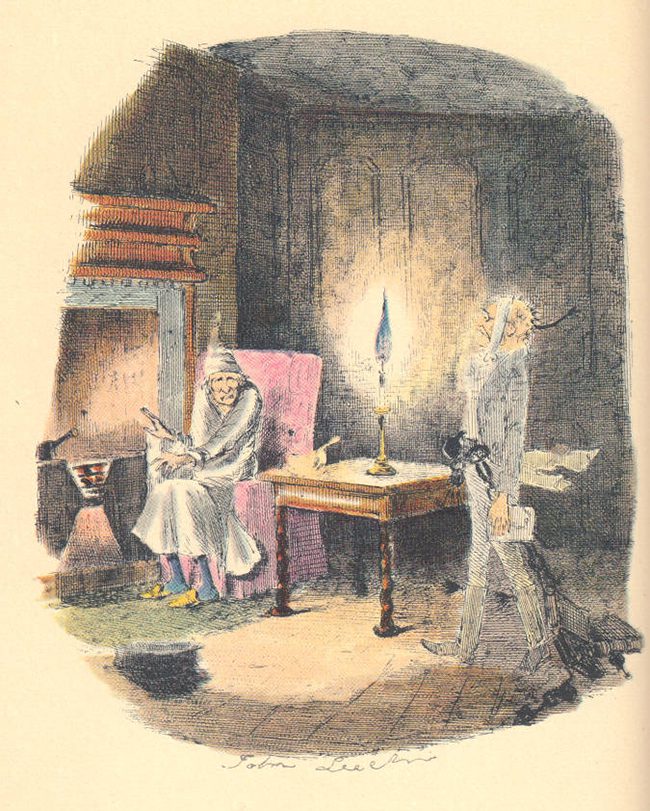

The story of A Christmas Carol is simple. Ebenezer Scrooge, a wealthy and close-hearted miser, is visited by the ghost of his old business partner, Jacob Marley, on Christmas Eve. Marley, covered in chains of sin and attachment to worldly possessions (chains he himself smelted through his callous actions in life), tells Scrooge that his fate will be the same as Marley’s if he does not mend his life. He then explains that three more Ghosts—the Ghost of Christmas Past, the Ghost of Christmas Present, and the Ghost of Christmas Future—will be visiting Scrooge. The first brings the old man to see his own past and the people who have impacted him, the second shows him the lives of those he knows, and the third shows that, on his death, Scrooge will not be missed by anyone. This experience leads Scrooge to repent of his ways and become a generous and caring man for the rest of his life.

This much of the plot virtually every film adaptation gets right. Another important feature that tends to be retained is the Cratchits, a poor but joyful family whose patriarch is in the employ of Mr. Scrooge. The Ghost of Christmas Present brings Scrooge to see the Cratchits (unbeknownst to them). While watching the family, he sees that, despite their relative poverty, they exhibit great love and gratitude. The member of the family who leaves the biggest impression on readers (and on Scrooge himself) is the smallest in stature: “Tiny” Tim. The boy is sickly and uses a crutch but radiates joy to all who know him. After Scrooge asks, the Ghost of Christmas Present tells him that, if nothing changes, the boy will soon be dead and buried. However, after his conversion, Scrooge works to ensure that the boy and his family are cared for, and Tiny Tim’s cruel fate is avoided.

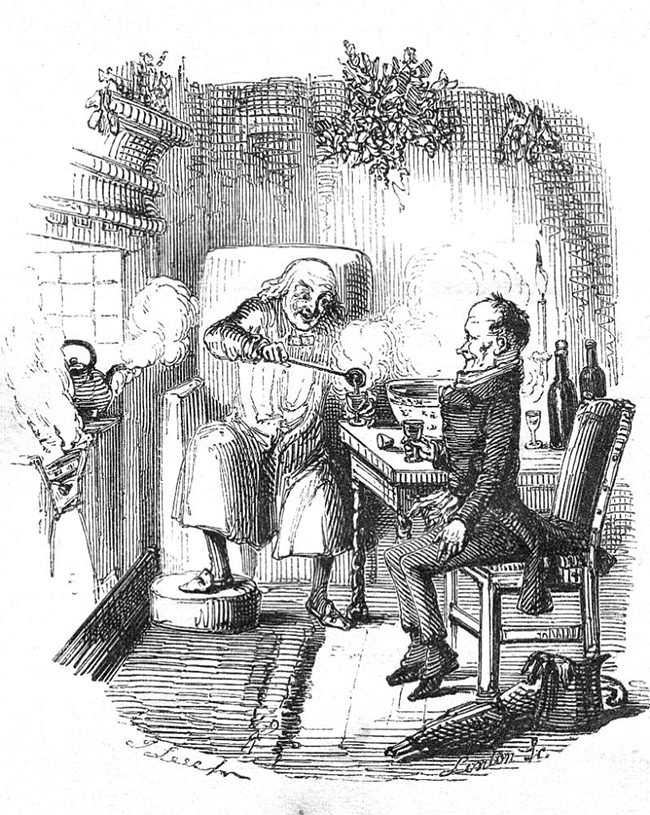

Anyone who has seen Scrooge’s transformation on screen has been touched by how the miser ultimately learns generosity and care for those in need. However, we should remember the fact that, in the original tale, he had an important model of these virtues: his old boss and mentor, Mr. Fezziwig. Unlike Scrooge, Fezziwig seems to have a natural affection for those over whom he has power and influence. He runs a business, but that business does not get in the way of his employees’ happiness. Indeed, Fezziwig magnanimously throws a Christmas party for his employees every year, providing an opportunity for celebration and community. Readers are privy (thanks to the Ghost of Christmas Past) to one of these parties, and we see the joy it brings.

While much has been made (with good reason) of the political and economic subtext of Dickens’ treatment of the kind-hearted, pre-industrial Fezziwig and the miserly, post-industrial Scrooge, it is the moral and theological sides of this contrast that most interest me. Dickens, though not a perfect model of virtue or theological precision, was a Christian. This faith informed his writing, not least in its vision of the right relation between rich and poor.

When discussing this article, my wife insisted that there was a quotation from Dickens’ late novel Little Dorrit that I ought to include. Having not read the book, I was hesitant, but now, having read the quotation, I see that my wife was correct (and that I ought to pick up the book soon). At one point in the novel, the titular Dorrit says that we ought to,

Be guided, only by the healer of the sick, the raiser of the dead, the friend of all who were afflicted and forlorn, the patient Master who shed tears of compassion for our infirmities. We cannot but be right if we put all the rest away, and do everything in remembrance of Him. There is no vengeance and no infliction of suffering in His life, I am sure. There can be no confusion in following Him, and seeking for no other footsteps, I am certain!

All Christian ethics presupposes the foundational imperative that man must ‘love his neighbor,’ especially those neighbors who are in some way ‘below’ him. Throughout His public ministry, Christ cared for the downtrodden and dejected. These were often people who—whether owing to their own fault or happenstance—lacked meaningful agency to improve their mournful stations. This is consistent with His public teaching, in which Jesus ensures us “blessed are the poor” and tells us “whatever you do to the least of these you do unto me.”

Christ’s own life modelled the love for those in need He tells us to practice. While healing lepers and showing kindness to tax collectors are obvious examples, the most significant way in which He has shown this love is, in fact, by His entire earthly mission. He, whom Christians believe to be true God from true God, became man and died on the Cross for us. I don’t want to fall into pious, saccharine platitudes, but this is the greatest instance of the great caring for the lesser in all history.

Our world is perhaps more obsessed with ‘power’ than it has ever been, but Christ’s life, death, and teaching stand as a reminder of what power is truly for. Power is meant for the good of everyone.

To return to A Christmas Carol, Fezziwig is a man who understands and lives out this truth. Though his dialogue takes up very little of this relatively short book, his character shines through in his actions. He was a devoted boss who ensured his employees were not only rewarded for their diligence but even given the chance to celebrate together.

Most theories of virtue ethics include the idea of exemplars. When a person wants to grow in a virtue, say generosity, he may have difficulty knowing where to begin. However, if he has seen other people who have exhibited that virtue, he has a place to start. Indeed, even a single instance can be crucial. This is often the role of historical figures such as saints or national heroes. But for Scrooge, that figure was Fezziwig.

At the beginning of the story, Scrooge is the opposite of his old employer. Instead of using his power for the good of his employees and those in need, he uses it to insulate himself from others. Interestingly, he doesn’t even use his wealth and power for his own pleasure; he simply accumulates it and cordons himself off from the outside world.

While perhaps less dramatic than actively lording power over others and attempting to wound them, this way of life is ultimately just as empty. It is also a way of life that is surprisingly tempting. As Christmas approaches, I am struck by how comfortable my life is, and how little time I spend serving those in need. I do my job, take care of my family, and give perfunctory donations to charity and my parish, but I very rarely go out of my way to actually care for those who are in need. I may not be a wealthy man like Scrooge, but I am always in danger of becoming like him. Thus I, like so many of us, am in need of a Fezziwig who can shake me from my worldly slumber.

There are families who have a tradition of reading A Christmas Carol each December. The reason for this is simple: it is a tale that is not deadened by repetition, for it reminds us of two crucial truths. First, each of us can become hardened to the world and devoid of love, as Scrooge is at the beginning of the story. But second, we are none of us hopeless cases in this life; we can all love more deeply.

May A Christmas Carol stay in our hearts the year round. And may the spirit of Fezziwig remain there as well.