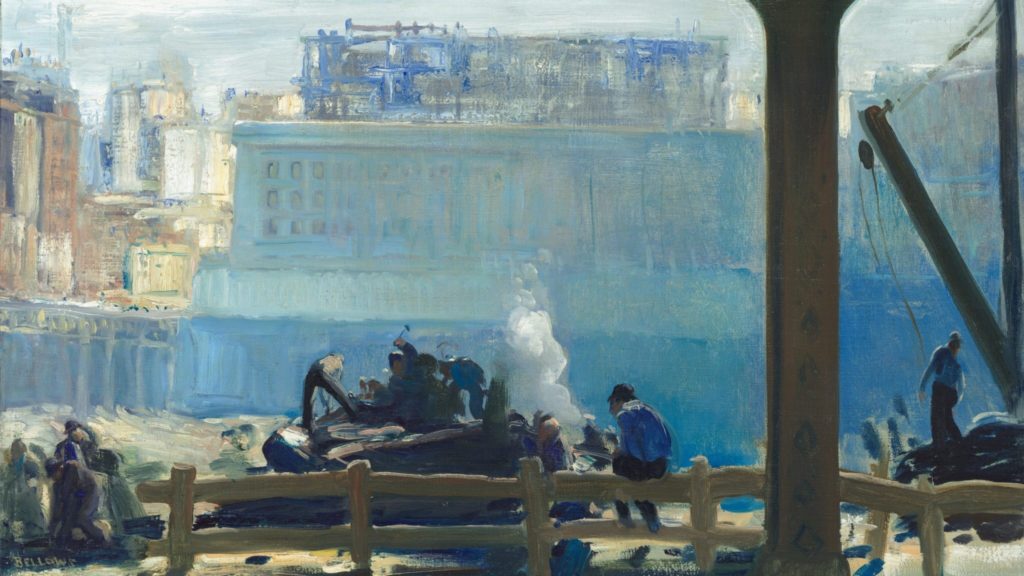

“Blue Morning” (1909) by George Bellows (1882-1925), located in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. Immigrants worked long and hard in the early 20th century in order to “make it” in America. This painting evokes these memories, depicting immigrants working on the laying of a foundation for a New York city skyscraper.

PHOTO: PUBLIC DOMAIN.

We are all Germans now. All of us in the West, not just my Wehrmacht-conscripted grandfather, wish we could repudiate the past wholesale and start at year zero. In hindsight, I now realize that the same forces that refashioned him into a very innocuous and inoffensive kind of ‘global citizen’ of America are now those in ascendance across the Occident. What started as a project to create the perfect post-German German is now a project to create the post-Western Westerner.

G. Henry Hofer was born in Germany in 1926, and his funeral service took place at a Lutheran church in Santa Monica, California. The pastor had never met my grandfather. His spirituality, like the rest of his life, was marked by itinerancy. He married my grandmother in Canada in the early 1950s in a Lutheran church. At various points in his life he attended Presbyterian and Episcopalian churches (he was even confirmed into the latter denomination), only to end up in an urn in an ultra-progressive church into which he had hardly set foot in decades.

His political life was equally pendular. He went from a Vietnam-era, anti-war Democrat to a Reagan Republican, and staunch advocate of the Iraq War and George W. Bush, to an avowed never-Trumper and Hillary Clinton supporter on his deathbed. When he spoke of Germany (which was rare) it was usually from the perspective of a proudly assimilated American disparaging the wimpy peaceniks of the Federal Republic.

My grandfather’s full name was Gunther Henry Höfer. The umlaut over the o in Höfer was dropped upon arrival in Canada, along with Gunther. He became ‘G. Henry Hofer’ from then on. A smart move in Canada and the U.S. in the 1950s.

In 2008, I visited my great-uncle in Mannheim, outside Frankfurt. He had come with my grandfather to Canada and then the U.S. only to return to Germany. In his apartment he produced a photo of my grandfather as a young boy with the Nazi armband around his sleeve. I now wonder why, out of the few pictures my uncle could save as he fled Danzig (now Gdańsk, Poland)—a “free city” until its annexation by the Third Reich in 1939—he held onto that one. Was it premeditated, so that he could show me pictures of my ‘Nazi-American’ grandfather?

My great-uncle Dieter, as far as I can tell, led his life according to the unofficial creed of Germany and Brussels—namely existentialism. The world is devoid of meaning except for what you make of it. This self-generated meaning in the face of nothingness is to be revered and followed by others as an example of heroic individualism. My great uncle made money in advertising in Germany, part of the nouveau riche that appeared due to the “economic miracle.” He told me he “felt nothing” when Germany was reunified, and that it was all just a scheme to enrich West German business interests with cheaper sources of labor and new markets for their goods. Anti-capitalism, anti-nationalism, and existentialism were my great uncle’s—and the German hard Left’s—holy trinity.

I never asked my grandfather if he was a Nazi. He was only seven years old when Hitler came to power. The advantage of interrogating the dead is that they can’t defend themselves, and when I ask his ghost if he approved of Hitler, I imagine his honest response (as a ten- or twelve-year-old, not as a self-conscious adult, ever-aware of Nazi war guilt) to be similar to that of Nobel Laureate Günter Grass, who also came from Danzig and went to school with my grandfather: “I can take care of the labelling and branding myself. As a member of the Hitler youth I was, in fact, a Young Nazi. A believer till the end. Not what one would call fanatical, not leading the pack, but with my eye, as if by reflex, fixed on the flag that was to mean ‘more than death’ to us, I kept pace in the rank and file. No doubts clouded my faith; nothing subversive like the clandestine distribution of leaflets can let me off the hook; no Goring joke made me suspicious. No, I saw my fatherland threatened, surrounded by enemies.”

German emigrants boarding a steamer in Hamburg, Germany, to go to the U.S. Originally published in Harper’s Weekly, November 7, 1874.

PHOTO: PUBLIC DOMAIN.

Like my grandfather, Günter Grass is curiously silent throughout his 400-page memoir about what drew him to Nazism. Gunther Hofer, I imagine, would have identified with Joachim Fest—father of German MEP Nicolaus Fest— who, in his memoir about the war years, said that his family had “passionately defended middle-class and civil virtues.” Such virtues reflected an “outmoded order,” a fundamentally bourgeois order, which the Nazis had either wiped out entirely or had driven into hiding from 1933-1945.

According to W.G. Sebald, in On the Natural History of Destruction, the German ‘economic miracle’ after the war—which replaced ruins with glimmering skyscrapers—was the sublimation of the Germans’ drive to erase the past by building atop it. The rise of new cities and the resettlement of 12 million Germans expelled from the East constituted at once a way to embrace liberal capitalist modernity and elide the pain of the past.

As Sebald puts it:

There was a tacit agreement, equally binding on everyone, that the true state of material and moral ruin in which the country found itself was not to be described. The darkest aspects of the final act of destruction, as experienced by the great majority of the German population, remained under a kind of taboo like a shameful family secret, a secret that perhaps could not even be privately acknowledged.

Just as the horrors of the firebombings, in which at least 600,000 German civilians died, were not to be mentioned, so too the memory of Hitler flitted away, according to Grass, almost without remark:

His departure was taken as only to be expected. Nor did I miss him particularly.… Nor did I later … suffer withdrawal symptoms. He was gone as if he had never been, had never quite existed and was now to be forgotten, as if you could live perfectly well without the Führer.

These are few and fleeting words for a Nobel Prize Laureate and member of the Waffen SS who positioned himself as the moral conscience of post-war Germany. As Joachim Fest notes, anti-nationalist guilt became a kind of leftist public performance of contrition, in which he who expressed compunction was elevated to a plane of moral purity above those of his uninitiated observers:

Some invented acts of resistance; others (as part of the game of contrition) sought out a prominent place on the bench of the self-accusers. But in all their lamentation, they were ready to defame anyone who didn’t do as they did and constantly beat their sinful breasts. When Günter Grass or any of the other countless self-accusers pointed to their own feelings of shame, they were not referring to any guilt on their own part—they felt themselves to be beyond reproach—but to the many reasons which everyone else had to be ashamed.

In the above, one can see more than a hint of the self-righteousness of the woke American left who, in adopting the new critical theory of guilt—‘white privilege,’ systemic racism, ‘spirit murder,’ etc.—condescends to those who “aren’t as far along in their journey.”

Yes, we are all Germans now. What started out as the uniqueness of German guilt has mushroomed into an all-encompassing Western guilt, now tied to the legacy of imperialism and the transatlantic slave trade. For Woodrow Wilson and other turn-of-the-century progressives, the Hegelianism of the German universities was to be emulated as Progressivism 1.0. Post-nationalist shame, interminable rituals of guilt, and the elevation of all that is non-Western to the status of the sacred are the lessons that Germany has to teach us.

Such is the point made in such books as Learning From the Germans: Race and the Memory of Evil by Susan Neiman. White Americans are presented as Nazis of a sort, orchestrators of genocide and enslavement which predates, but is no less horrific than, the gas chambers and concentration camps. “America never did the hard work to face its past that Germany has done,” states Neiman, as if the Civil War, the Civil Rights Movement, the election of Barack Obama, affirmative action programs and the like had never occurred.

We are all Germans now—because we can never finish atoning for our sins, never finish living down our singularly heinous crimes as (white heterosexual male) Americans. As any right-of-center German voter or closet Trump supporter can tell you, any attempt to affirm any positive national values is considered ‘radical historical revisionism’—essentially, the specter of Fascism rearing its ugly head.

How had my own grandfather—a self-identified conservative—found so little in the way of refuge in “the permanent things”? True, he always proudly considered himself an assimilated American and set aside time for the august affair of the presidential inauguration every four years. True, he lived the majority of his life in Santa Monica, and thus established roots there, extolling the virtues of the region almost as much as those of America in general. But his life of faith, and his political convictions, were peripatetic. Much of his being seemed to be defined more by the restlessness of a liberal: too squeamish to be pinned down to any certainties that might, at some point, fall out of favor.

Trenchant political commentators and academics of the post-war West are now starting to provide something in the way of an explanation of what happened to him and post-war Western conservatism. Perhaps G. Henry Hofer’s fluidity in his spiritual and political life—a fluidity that I see as flawed because it does not lead to a life of rooted convictions—evidences an innate defect in post-war Western and American conservatism.

According to R.R. Reno, the 1960s were not “countercultural” in the slightest. Already in the 1940s and ‘50s, philosophers like Karl Popper and economists like Friedrich Hayek advocated the ideals of “openness” and “disenchantment” as the necessary response to any authoritarian impulse in society. The “Strong Gods” (as Reno calls them) of nationalism, religious faith, and political belief were to be replaced by the “little worlds” of individual fulfillment, personal meaning, and technocratic management. This was the only option if the West were to avoid further conflagrations comparable to WWI and WWII.

Furthermore, American conservatives—by embracing a libertarian-inflected economic and philosophical outlook, in which the former subsumes and devours the latter—inadvertently supported the rise of the cultural left. The influence of Angela Merkel’s CDU in Germany—despite its suicidal decision to open the floodgates to over a million refugees in 2015—even suggests that Europe’s center-right has completely swallowed the specious view that multiculturalism and traditional values are, indeed, somehow compatible.

American political theorist Gladden Pappin sums up the ideological abyss into which much of American—and, again, Western—conservatism has fallen with increasing celerity since the end of the Cold War, when anti-communist sentiment provided the Right with at least some sense of transcendent purpose:

Modern American conservatives … in making their task the defense of liberalism in its market-oriented and social aspects, have made themselves unable to articulate the purpose of power…. Liberalism was a theory to explain the state; and conservatism was a theory to explain liberties, but not the state.

In his critique of Lockean liberalism—the de facto ideological credo of both the progressive left and the libertarian right—Yoram Hazony likewise explains how contemporary political pieties of the postwar consensus fall short in fundamental cultural, spiritual, and even anthropological senses. Locke conjures up a “dream world,” Hazony says, in which every human relationship is the product of individual consent, despite the obvious fact that no individual chooses where or by whom he is born, nor whether to enter into some contract with the state:

A Lockean theory of the state does not enable us to understand, much less justify, the existence of the national state and the ties of obligation that give it shape.… His political theory summoned into being a dream-world, a utopian vision, in which the political institutions of the Jewish and Christian world—the national state, community, family and religious tradition—appear to have no reason to exist. All of these are institutions that result from and impart bonds of loyalty and common purpose to human collectives, creating borders and boundaries between one group and another, establishing ties to future and past generations, and offering a glimpse beyond the present to something higher. An individual who has no motives other than to preserve his life and expand his property, and who is under no obligations other than those to which he has consented, will have little need for any of these things.

Curiously, the free-floating individual—unbound by anything other than consent and choice—serves a paradoxically two-pronged agenda: it dovetails both with the borderless supranationalism of the EU, the MNCs, and the globalist acolytes of these everywhere while also serving the cultural Marxism which militates against any set boundaries of national preservation—most of all in western nations. In The Death of the West, Patrick J. Buchanan referred to this phenomenon as a kind of “international socialism” which emerged in the wake of Soviet defeat.

Indeed, everything from unchecked immigration to Europe and North America to green energy mandates that are most onerous to the West can be seen as a kind of leveling of the playing field, so to speak. Once there is no discernible difference between the West and the non-West in terms of standard of living, once the preference for Western values has been diluted in a sea of multicultural demographic redistribution, then the West’s atonement for its Nazi, racist past will be complete. This is the secular crusade to cleanse the West of its past.

My grandfather didn’t live to see the Trump victory or his presidency. He died on September 7, 2015. I cannot say whether he would have changed his mind about Trump and come to agree that comparing Trump or his supporters to Nazis were overblown. I have no idea whether he would have been lucid enough to grasp the stirring of national conservatism gaining momentum in America, as well as through populist-nationalist parties in Europe such as VOX in Spain, Fidesz in Hungary, Law and Justice in Poland, and AfD in Germany.

I have no way of knowing whether my grandfather and grandmother, from their places of eternal repose, might think of me as one of the lemmings seduced by crypto-authoritarian individuals and ideals. What I can say with certainty is that I believe, as Reno puts it in Return of the Strong Gods, that it is, in fact, time for the 20th century to be put to rest. It is time to stop fearing the return of 1933 and to restore the “Strong Gods” of faith, traditional family, and nation. Like Hazony and Pappin, I believe that it is time for conservative politics to convey a theory of the state that promotes and defends these principles—rather than simply asserting the right to individual autonomy in the private sphere of market transactions.

For holding such beliefs, I, and those like me, must be prepared to be characterized as ‘Nazis.’ But Western conservatism has already spent a half-century, on its heels, trying to fend off such slander. At a certain point, tactical retreat has to come to an end—and conservatives will have to stand their ground. That time is now.