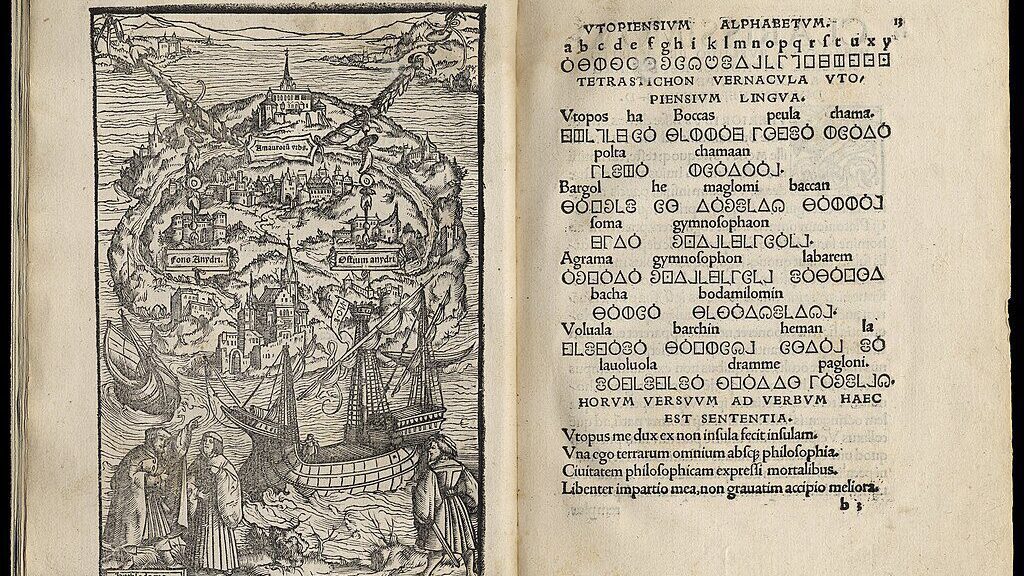

Pages 12 and 13 of Thomas More’s Utopia in the edition printed by Johannes Frobenius in 1518, Basel.

The word ‘utopia’ is almost unique in our lexicon; it has of late become entirely synonymous with its perceived opposite. That is to say, two words, set up like integral columns, have collapsed in on one another, bringing with them their distinct utility. In the common imagination, ‘utopia’ and ‘dystopia’ are now one and the same. There is great irony in this, but not that which is often pointed out. The fact that the supposedly ‘perfect’ world is inevitably a nightmare has in our time come to be recognized as something of the truism, and the point is often received with boredom.

My point here might seem like pedantic nit-picking about synonyms and antonyms, but it reveals a vital distinction. Sloppy thinking about utopias can encourage political thinking that is weak at best and dangerous at worst.

In the original sense of the word, in Greek, ‘utopia’ literally means ‘No-Place.’ But, like so many other terms, ‘utopia’ has, like a flower long since plucked from the stem, been passed around and become wilted, creased, lustreless, and dry. Pressed in the pages of a student’s notebook, it lacks something essential: life. We must, then, return ad fontes—to where the idea first arose. We must return to St. Thomas More and his Utopia.

The first thing a reader notices on opening this 16th century work is its strangeness. Broken up into two parts (or ‘books’), the work is narrated by More, though much of the most interesting content is in the voice of the fictitious world-traveler, Raphael Hythloday. Hythloday (whose name means ‘nonsense expert’) has returned from a trip to the New World and tells of his discovery of the fantastical, seemingly perfect land of Utopia. This storyteller describes the laws and ways of life that characterise the land of Utopia, hoping that, though strange to European ears, they might nonetheless inspire his audience.

Part of what makes the work so odd is its apparent inconsistency with what we know of More’s own thought and ways of life. For instance, we find in Utopia a place where flagellation is heavily criticised, not only as a disruptive influence, but on first principles:

If such a life is good, and if we are supposed, indeed obliged, to help others to it, why shouldn’t we first of all seek it for ourselves, to whom we owe no less charity than to anyone else? When nature prompts you to be kind to your neighbours, she does not mean that you should be cruel to yourself.

And yet we know that More himself wore a hairshirt beneath his vestments and made use of a penitential discipline. What, then, is the relationship between the man and his imagined society?

This is no easy question. Profound disagreements arise in any discussion of the book; indeed, many cannot even agree on what, precisely, More’s purpose was in writing it. Socialists, for instance, look back and claim it as a proto-progenitor, as an example of an early and codified critique of private property, while others take it as precisely the opposite, a stringent critique of common ownership.

Is it, then, a presentation of a perfect example of commonwealth, in which all the iniquities and injustices of More’s contemporary world are assuaged and fixed? Or is it a subtle warning of the fate of all those who would believe the problems of life can be perpetually solved by the rearrangement of the societal structure?

We needn’t align with either Karl Marx or Ayn Rand in this battle, for both such positions are anachronistic and miss the point. So too, in fact, is the way we approach this book. For we are apt now to approach texts, particularly in the humanities, as the fruits of either the ‘creative’ mind or the ‘analytic,’ with fiction and non-fiction as their chief examples. Most readers of Utopia today believe it is the latter, a work making a criticism of, or commentary on, society. They therefore focus almost exclusively on its second part, where More, in the voice of Hythloday, explains in great detail the manners, mores, constitution, and pattern of society on Utopia. In the minds of many contemporary readers, it is best interpreted as something like a political tract, set in an amusing but dated Renaissance frame of narrative and dialogue—more a quirk of its time than an integral component.

Conversely, there are some, though not many, who pick it up with expectation of a diverting fiction, written by a man in his idle hours for simple diversion and pleasure. Utopia, for this latter reader, is something akin to an amusing safari, in which More points out all the various and alien ideas by which another society could be possessed. Of the two approaches, because of our inclinations, the latter, while being no closer to understanding More’s true intentions, is the likelier to stumble upon them. For he reads it intending pure diversion, and with his only prejudice being toward enjoyment—he cares little whether Utopia is possible or not—and in allowing his mind simply to wander its conurbations and smile wryly at its conception, he is not far from the gentle playfulness which is More’s way.

If I am correct, then we must peruse that first part of the book rather than passing swiftly over it, as so many readers, and even professors, do. It is there that the scene is set and the character of More first meets his friend Peter Gilles and the stranger Hythloday. If we pay no heed to this in our eagerness and haste to reach the perceived ‘meat’ of the text, we are in danger of denying the amuse-bouche which sets forth the tone of the entire meal.

The first, brief conversation of the work has several characters standing in the street, preoccupied with the question of instructing princes. After Hythloday gives his credentials as a world traveller by describing various other places with radically different customs (which the narrator More nevertheless refers to as “civilised”) Peter Gilles, More’s companion, tells him this:

“My dear Raphael,” he said. “I’m surprised that you don’t enter some king’s service; for I don’t know of a single prince who wouldn’t be eager to employ you. Your learning and your knowledge of various countries and peoples would entertain him, while your advice and your supply of examples would be very helpful in the council chamber. Thus you might advance your own interests and be useful at the same time to all your relatives and friends.”

This is instructive, for it gives us a contemporary description of the role of the courtier, his function, and his designs, yet to be dismantled by the cynicism of Hythloday’s reply. Most surprising to modern sensibilities is that mention of entertainment. It is clear this is no adjunct quality but described as an equal partner to the role of advice. We may now find it hard to believe, when we observe the rather drab and inconsequential figures glimpsed in the shadows cast by our modern leaders, that at one time, prized above mere competence in the handling of statistics or the collating of polling data, was an advisor’s wit and humour. For learning was something that by necessity entertained and displayed a certain kind of playfulness in order that it might be applied to politics.

This no doubt offends our sensibilities, however much we may claim to prize humour. Politics after all is a serious business. It offers little opportunity for jokes or the capacity for play. Pleasure, having long ceased to be a public attitude, has been annexed to the purely private individual, leaving behind only solemnity. We see our loss in places as disparate as our own architecture (which eschews all ornament), to our principal means of political advice becoming the weaponisation of mass data. Yet, more than the mere pretensions of an effete and self-satisfied class, this ideal of learning, of taking play seriously and approaching serious matters with levity, is understood as part of the serio ludere tradition. In serio ludere, the unexamined assumptions of the time could be submitted to critique by approaching them as a lively distortion of the current state of things, which nonetheless enlightens by its disruption. We might say that just as music, drama, and the masque were all integral parts of court life, so too was the intellect, which was of little use if it could not dance.

Nevertheless, there is one aspect of the courtier that the modern reader will no doubt recognise. To clutch the cloak-tail of power in advance of the interests of oneself and one’s friends, after all, is no more alien now as it was then, though our attitude has become one of more ostentatious opprobrium. Perhaps the only difference is that More wrote at a time when a ruling class existed precisely for the unashamed purpose of ruling, rather than the more euphemistic aim of ‘leading.’ In such cases there appears little need to hide one’s personal interests, at least insofar as they exist. It is the pretension of our own day that all those who aim to rule must first pay homage to ideas of ‘serving’ one’s polity, as if it were an ascetic exercise. Perhaps now it is. However, Hythloday says he has already served the interests of his friends by distributing his wealth and possessions, and consequently is quite happy. “Very few courtiers,” he adds, “however splendid, can say that.” He goes on to note that, “most princes apply themselves to the arts of war, in which I have neither ability nor interest, instead of to the good arts of peace,” and that, in any case, all new advice would fall on deaf ears, for, “It is only natural, of course, that each man should think his own opinions best: the crow loves his fledgling, the ape his cub.”

All through this little episode, More is telling us how readers ought to approach the Utopia itself. He introduces us both to the character of Hythloday and the purpose which he serves, and it is clear he has neither the desire nor the temperament for politics. His happiness lies in the distribution of his estate, which one can hardly call prudent in a statesman. He does not find much interest in competition. In fact, much like the products of modernity, he displays an uncanny interest in approaching the world at the resolution of the system. Nowhere is this better displayed than when, in a conversation with the Archbishop of Canterbury, he attempts to describe why so many thieves persist despite the veritable mass of hangings that take place, “with as many as twenty at a time being hanged on a single gallows.”

His description of the contemporary structure of English society as the root of this felonious behaviour would make any modern sociologist proud. He begins by observing the idle trains of retainers living beneath the patronage of noble lords. These men, armed and violent, who on their masters’ deaths are turfed out, are apt to turn towards a life of robbery and extortion precisely because of their former comfortable existence and their distinct lack of trade. Furthermore, the enclosure of common land formerly used for the grazing of sheep has driven those making a subsistence living on small holding impossible and has likewise driven them to crime. Hythloday concludes:

If you do not find a cure for these evils, it is futile to boast of your justice in punishing theft. Your policy may look superficially like justice, but in reality it is neither just nor practical. If you allow young folk to be abominably brought up and their characters corrupted, little by little, from childhood; and if then you punish them as grownups for committing crimes to which their early training has inclined them, what else is this, I ask, but first making thieves and then punishing them for it?

Hythloday is closer to our contemporary attitudes than More could ever have imagined. Yet while such analysis is no doubt familiar to all of us—and not without insight—it is important only so much as it tells us of Hythloday’s own thinking. For instance, if More was merely attempting to denounce his own time’s mode of thought, why not merely produce a tract? Unlike a tract, Utopia is a subtle tool, an exercise for the active mind. In looking afresh at this beginning, where More sets up the question of how best to advise a prince, we come to understand this exercise as the creation of an arena for the display of wit and the capacity to read one’s own world through the gaps of another.

This is done by creating a kind of inverted image of his own society. More grants a means of reading through the cracks of this inversion, of listening at the silences and searching in the shadows of Utopia, in order that he may find with fresh ears and eyes the hypocrisies of his own age, unmoored from prejudice and vested interests.

We know that few ages explicitly celebrate naked selfishness and cupidity. Yet we also know that the distance between a society’s espoused virtues and vices is the arena where life takes place. Thus, in Utopia, no man is awarded with money or estates, for no man wants for anything, being fed, housed, and clothed in such a manner as to sustain his life and labour and to dampen his jealousies with equality. We find on first glance a society that, unlike More’s own, has resolved the gap between espoused virtues and quotidian vice. Equality is not just the espoused virtue of this society, but its very manner. What surprise there is then, on reading of an institution of marriage not divided up by lot, but, after naked inspection, a veritable market hierarchy; for while we learn that, “though some men are captured by beauty alone, none are held except by virtue and compliance,” if such virtue was equally distributed, (indeed, if such beauty) why not randomly assign spouses? If not, and one concedes this point—that sexual or romantic jealousy is an unfortunate and obstinate remnant of human nature—is the reader to suppose that the green-eyed monster that drove Othello to kill his beloved Desdemona is only a small cause for human dispute? The same sort of thing occurs in various other places, most notably in the erecting of monuments for military and strategic success.

How does society get past the disparity of its espoused virtues and its enacted ones? The answer is its use of categorisation. In our world, heroism, genius, celebrity, and a myriad of other phrases are used as a means of providing cover from deviations in the blanket acceptance of equality, for we find it impossible entirely to jettison our desire for exemplars. Instead, the virtues we attach to such titles change, even if the individuals do not. So we have champions of equality that win medals running the one hundred metre sprint or performing in Premier League football teams, despite the incongruity of the term.

Similar things happen in Utopia, where the divorce of reputation from property is used as the means of permitting selfish desire by another name, even while material proprietary claims are not permitted—such as with the monuments to strategic success, which offer no monetary benefit (but one can nevertheless surmise are natural fulcrums of envy). Consequently, a man’s name has worth, but it may not be said to be his ‘property.’ No wonder then, that Utopia has no lawyers, for the matter of slander is surely moot if a man’s reputation is not treated as his property. In other words, while both societies may differ in vital respects, both More’s time and his imagined world fail to renounce the same necessary sleight of hand, an expedient that is both necessary to negotiate, and deferential towards, human nature.

So, while Utopia may well be described as dystopic, we must cease from merely nodding at the common irony. Despite obvious differences, at the heart of all societies is their capacity to confront and either retard or cultivate the human being in all his roundness. It is in the play of the mind that such things can be explored, and it is in that exploration that the courtier must exercise himself fully to be of any use.

And so, I invite all readers to imagine the inversion of their own society: one in which beauty and learning are the highest of virtues, where nobility and taste are inculcated for their service, and in which ugliness is not just castigated but its causes suppressed. More teaches us that such dreams always harbour nightmares in their shadows—that much is true of the utopia / dystopia elision. Yet the real task is to take that dream and use it, not merely as a warning, but as an arena by which thought may dance, and in dancing, interrogate the very realities of our own times. Only by doing so, and by viewing our own society in the iniquities of its opposite, can we hope to understand it despite our pretensions. For it is in such shadows that we find our home.