Photo by James Vaughn, Flickr / CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 Deed

Attempting to expound someone else’s thought is always a high-risk endeavor. But since I recently declared Dalmacio Negro Pavón the most significant political thinker in Spain in recent decades, with all due caution, I will outline what I consider to be some of the interpretive keys to Negro Pavón’s thought.

The work of Dalmacio Negro Pavón reveals that politics cannot be understood without anthropology: the various conceptions of humanity throughout history are not mere theories but paradigms that have shaped the lives of peoples and conditioned political thought.

The last stand of Britain’s patriots against the invading hordes was at Dorking, a market town in Surrey, thirty kilometers outside London. Despite their heroism, they would be defeated, the empire dismembered, and the victors would impose a bitter, draconian peace on the defeated.

This is neither past history nor, one hopes, future prophecy, but a seminal work of a fascinating sub-genre of popular literature. The Battle of Dorking, first published anonymously in Blackwood’s Magazine in May 1871, was a pioneering work in the field of invasion literature (or “Future War” as a recent L.W. Currey, Inc. book catalogue calls it). It was written by Sir George Tomkyns Chesney, a British general and veteran hero of the Sepoy Rebellion of 1857.

In the shadow of the conclusion of the Franco-Prussian War and the declaration of the German Empire, it was written as a call to military preparedness and to warn of the dangers of a German invasion of Britain. The story is told as if narrated by an eyewitness or a volunteer of a conflict that would take place in 1925. Dorking may have been written for didactic reasons, but it would not only be a popular success; it would launch a literary tradition that endures to this day. Science fiction historian E.F. Bleiler described it as “the first significant British imaginary war story and also the finest and most influential example of the subgenre.” Invasion, or Future War, novels and films would appear regularly throughout the 20th century and even later. The 2012 remake of John Milius’s 1984 classic Red Dawn has North Korea (originally China, but changed by MGM in post-production to avoid offending Beijing) invading the United States. The sub-genre is connected to the better-known genre of alternate history, seen in a work such as Philip K. Dick’s 1962 The Man in the High Castle.

The theme would be popular in Anglo-American and (according to the L.W. Currey catalogue) even German popular literature. There would be ‘serious’ treatments of the subject and more sensational, pulpy versions; left-leaning narratives and right-leaning ones; atheistic and religious versions. Sometimes the invader won and other times he was defeated. The invading power was often Germany—a real or imaginary version—but other times it was Russia, China, or Japan. While the genre overlaps with the lurid ‘Yellow Peril’ literature of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, some of the most brutal or savage actions in these books were done by European invaders rather than by Asians. Books of this type often crossed over into outright science fiction, with the invaders (and sometimes the defenders) perfecting some sort of super weapon. The future war in question was sometimes set in the far future but usually seemed to be set in a much more alarming near future just out of reach, an era not so different or distant from the time when these books were first published.

British historian I.F. Clarke was the great historian of future war fiction and traced the genre back to obscure publications in the 18th and even in the 17th century. Clarke even discovered an 1851 work about the invasion of England by France under President Louis Napoleon (the future Emperor Napoleon III). But it was Chesney’s Dorking that opened the literary floodgates. In 1880, Canadian-born Pierton W. Dooner published in San Francisco The Last Days of the Republic, a very early ‘Yellow Peril’ novel, where it is China that subjugates the United States not so much by military invasion but by subversion from within as Chinese coolies brought in as laborers rise to power. “Immigration becomes invasion” as the immigrant population gains power while, “The white population no longer continued to increase; white immigration had ceased; and the causes, which under a healthy system at home would have operated to swell the population, had likewise terminated; for marriage had almost fallen into disuse.”

As the Chinese population increases, moving beyond California, they succeed in becoming citizens and gaining political power while waging a race war. Dooner’s book, which is both racist and dull, sees the Chinese as remaining loyal to their Confucian traditions and disciplined in their old country ways. In the end, they use the American political system and federal government against their adversaries in order to take power. Ironically, Dooner’s screed appeared only two years before the passage by Congress of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which would limit immigration from China for more than fifty years.

Many of the future war or invasion writers were hacks like Dooner. But others were talented and famous. H.G. Wells’ renowned 1897 War of the Worlds is about a Martian invasion of England; his less known 1908 War in the Air features a German air invasion of America (where the Germans are surprised by an Asiatic air invasion of America). Classic works of pre-World War One espionage by Erskine Childers and John Buchan are about threats of German invasion, but without the actual invasion. The great Hector Hugh Munro (“Saki”) wrote a 1913 novel about a successful German invasion of Britain, When William Came, that is far inferior to his delightful short stories. The eccentric M.P. Shiel, author of the classic Last Man novel The Purple Cloud, would write not one but two ‘Yellow Peril’ Chinese invasion novels, The Yellow Danger (1898) and The Dragon (1913).

There were so many invasion novels between 1871 and the First World War that they would have to be parodied, and who better than P.G. Wodehouse to do so? In his 1909 comic novella The Swoop!, or How Clarence Saved England, Britain is invaded by nine foreign armies: “England was not merely beneath the heel of the invader. It was beneath the heels of nine invaders. There was barely standing-room.” The Germans are joined by the forces of the Somali Mad Mullah, Russians, Young Turks, Moroccan brigands under Raisuli, the armies of China and Monaco, the Swiss Navy, and “dark-skinned warriors from the distant isle of Bollygolla.”

The genre would survive Wodehouse and continue after the First World War. American adventurer and war correspondent Floyd Gibbons would pen a well-written take on the theme in 1929 with The Red Napoleon, whose titular character, Karakhan of Kazan, half-Tatar and half-Cossack, seizes power in the Soviet Union, conquers Europe (held up briefly in Italy by a heroic Benito Mussolini), and then proceeds to invade the Americas.

More books would follow in the 1930s (a particularly good time to write about invasions) and 1940s. But the biggest and most ambitious iteration of invasion literature ever written would not appear in book form (not until many decades later) but in the humble pages of American pulp magazines.

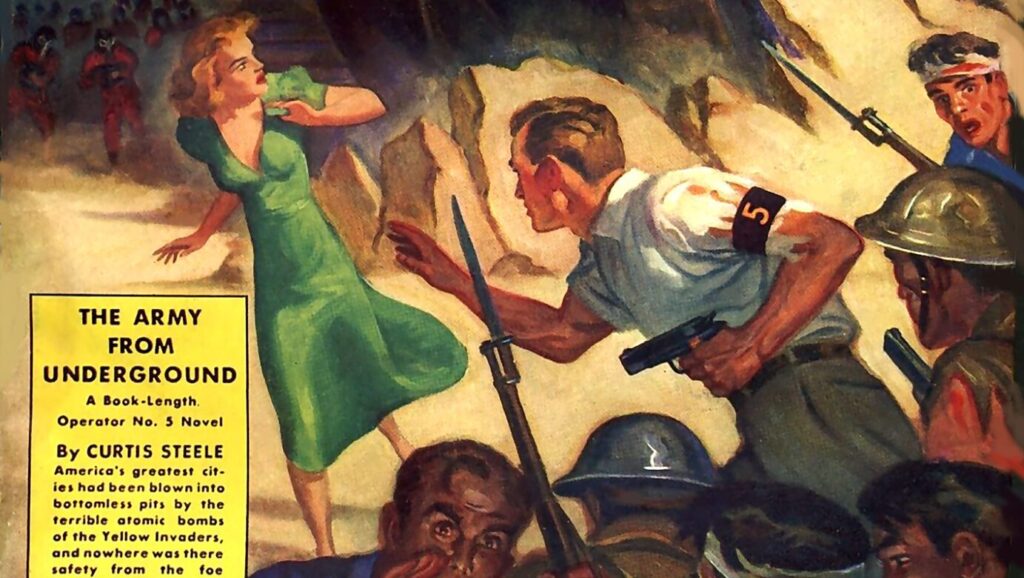

Secret Service Operator Number 5 was one of several single character hero pulp magazines to appear in the United States in the ‘30s (the first was The Shadow in 1931), debuting in 1934. These particular hero pulps (‘pulp’ because of the cheap paper they were printed on) magazines were precursors to the comic book superheroes that would begin to appear by the end of the decade (Superman in 1938 and Batman in 1939). But Operator 5 was not a hero in tights and didn’t have super powers. He was, at first anyway, a spy and a government agent. The character’s creator, pulpster Frederick C. Davis, described his mission as “Operator 5 must save the United States from total destruction in every story, every month.” This was not an easy task for a writer. Each monthly edition was essentially a novel of 60,000 words published under the house name “Curtis Steele.” Davis, Emile C. Tepperman, and Wayne Rogers would write all of the Operator 5 adventures under the Curtis Steele moniker.

Operator 5, “one of the greatest pulp heroes found in the pages behind the gaudy covers that attracted so many,” was six-foot-tall, blue-eyed Jimmy Christopher, “America’s Undercover Ace.” His father was a spy, as was his twin sister, Nan. He was a master of disguise and expert in the use of all sorts of weapons; he was a deadly swordsman. He began as an agent, but would have to become something more.

In 1936, after two years of fighting invading Orientals, crime lords, subversion, and latter-day Aztecs, Christopher and his crew took on their greatest challenge, the Central Empire and its Purple Emperor, in the June 1936 issue of Secret Service Operator Number 5. This would be the beginning of the Purple War Saga, 14 action-packed issues of the ten-cent magazine and more than half a million words of conquest and carnage across America, affectionately dubbed the “War and Peace of the Pulps.” Writer Will Murray describes the Purple War story arc as “a unique event in the pulp magazines—an ongoing open-ended serial in which the United States is not only invaded but virtually defeated.”

The Central Empire is essentially Germany, with “the crossed broadsword and severed head” being their insignia. Already masters of Europe and most of Asia, they invade Canada first, then move south. Unlike past examples of invasion literature, this series is not particularly didactic. Americans are described as having thought that their oceans would protect them from foreign invaders, and Christopher muses at one point that “our countrymen have lived softly, in comfort, for too long,” but the pulps were not about policy but about excitement.

The Purple War saga, first published in book form in its entirety only in 2019 by Altus Press (now Steeger Books), sees Operator 5 go from undercover government operative to soldier to the leader of guerrilla forces waging unremitting underground resistance against a seemingly unstoppable enemy that steadily conquers most of the United States. Midway through the series, the Purple Emperor is almost triumphant and planning his coronation in his new Dominion of North America. Christopher endures despair and almost succumbs to defeat. The Central Empire uses poison gas and biological warfare; it massacres women and children, at one point creating a barrier of 17,000 women and children hoisted onto crosses to keep the patriots at bay. The purple invaders bring in hordes of savage Mongol warriors to help them complete their task.

The Purple Emperor is assassinated only to be replaced by his even more sadistic son; the American patriots suffer terrible reverses; entire populations are wiped out by the invaders; regular forces are replaced by “Operator 5’s partisan skirmishers” and units such as the Storm’s Northern Wyoming Riflemen, the Fifth Oregon Cavalry, MacPherson’s Arizona Scouts, and the Fifth Kansas Volunteer Riflemen. There are hairbreadth escapes and daring plots; victory turns into bitter defeat, and almost certain defeat turns into victory.

In the end, the Americans triumph, but the country is devastated: the countryside is rife with gangs of Purple Empire soldiers turned bandits and cutthroats, the economy is in shambles, and more than a tenth of the country’s population killed. It is no surprise that the Encyclopedia of Science Fiction describes it as “almost certainly the longest sustained narrative published in the 1930s pulps, and one of the darkest.” Heady reading for teenage American boys who would in a few years be on the island of Guadalcanal and on the beaches of Normandy.

The Purple War stories were written by the prolific Emile Clemens Tepperman (1899-1951), the second of the Operator 5 writers using the name Curtis Steele. Little is known about Tepperman except that he was born and died in New York City to Russian-born parents. His occupation was listed on a census form as insurance broker, but aside from the massive Purple War undertaking, he wrote many other pulp stories in The Spider, The Avenger, and Secret Agent X magazines. None of his stories seemed to have been published in book form in his lifetime, and none appeared in hardcover until the deluxe 2019 two-volume Complete Purple Wars.

Tepperman’s Purple Wars is not great literature. Tom Johnson, an admirer of the stories who penned the afterword to the hardcover complete edition, notes the errors in continuity and character that occasionally crop up. Some of the plotting is slapdash, even by the standard of the pulps. He notes that when it came to battles with the enemy, one of two things would happen: “If Operator 5 led the attack, we would win the battle. If Operator 5 had to be somewhere else, the battle was going to be a suicide mission.” I give Tepperman a bit of slack because six months into the Purple Invasion saga, he took on writing The Spider (not to be confused with the much later 1962 Spider-Man) as well. Very few writers of the period would have had the intestinal fortitude to write two pulps at the same time.

What Tepperman delivered in abundance was action, heroism, and finally, victory. They are enjoyable reads if spaced out, approached in the proper spirit, and read as escapist literature from a better world that almost no longer exists. A glass of good American craft beer, or better yet, Kentucky bourbon, makes it even better. One remembers that image from Milius’s Red Dawn at Partisan Rock: “In the early days of World War Three, guerillas, mostly children, placed the names of their lost upon this rock.” Steeger Books (formerly Altus Press) is to be commended for making so much of the long-lost pulp adventures of ninety years ago available to the reading public.

At the end of the cycle, Jimmy Christopher, like Cincinnatus of old, would eschew high office and return home—home in this case being his old job of foreign invasion fighting for the Secret Service. The pulp would last only about a year longer, until the November/December 1939 issue, with Operator 5 fighting the menace of the Yellow Vulture. The bloody, no-holds-barred war of invasion and counter-invasion, defeat, despair, and defiance that the Purple Wars had anticipated was all too real now on the battlefields of Europe, Asia, and Africa.