Mosaic in the chapel of Our Lady of Guadalupe in the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington, D.C. by Fr. Lawrence Lew, O.P.

The work of Dalmacio Negro Pavón reveals that politics cannot be understood without anthropology: the various conceptions of humanity throughout history are not mere theories but paradigms that have shaped the lives of peoples and conditioned political thought.

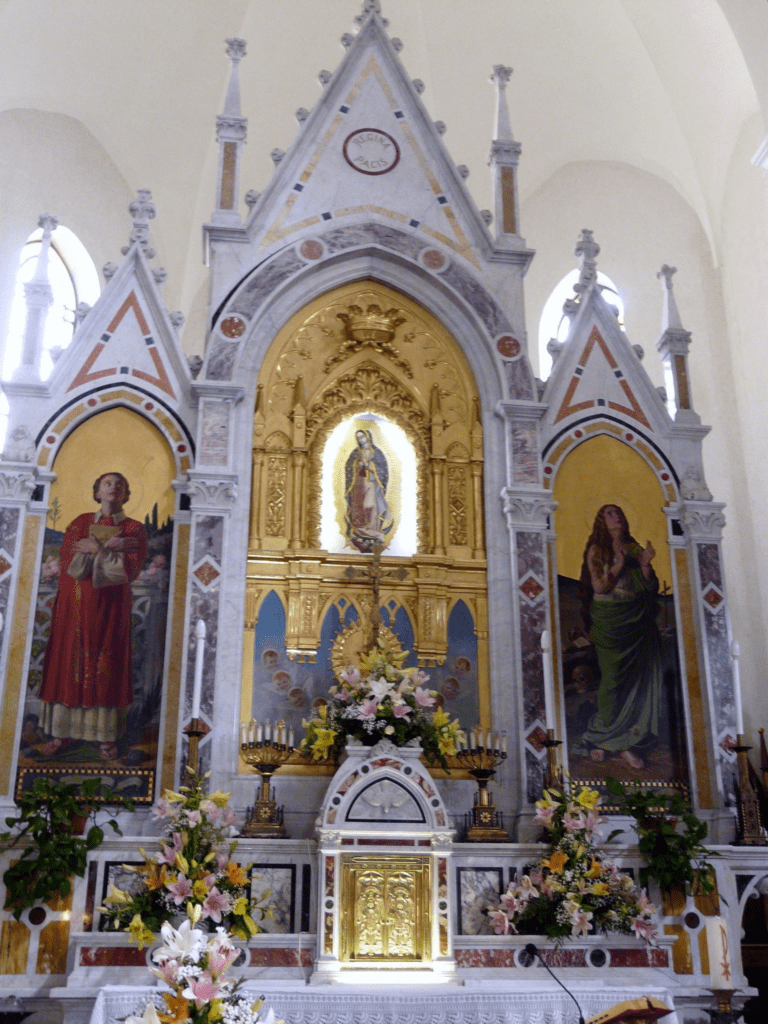

Not too far north of the sea, in a hamlet between green hills, stands a picturesque gothic church whose recently rebuilt white and grey façade boasts shining icons. Through doors bearing the bronze medallion of Christopher Columbus, we come to an interior serving as the sanctuary to an image of the Virgin of Guadalupe, for whom the Genovese commune of St. Stefano d’Aveto holds a celebration every August. The Madonna in question is not Spain’s Virgin of Guadalupe, whose veneration here in Liguria—were we to encounter it—would itself demand some explanation. But no, it is Mexico’s patroness that greets us at St. Stefano, her presence in this corner of Italy implying a leap across not only the Mediterranean Sea, but the Atlantic Ocean.

Far away from the peace of this place, her point of origin has recently marked an important anniversary. On September 16th, Mexico was commemorating 500 years since the fall of the Aztec Empire. It was a strange anniversary. The date itself corresponds to the country’s Independence Day, harkening back to 1810, and is quite unrelated to the Aztecs, whose capital was toppled on August 13th, 1521. Just how these two are meant to be linked is clarified by a short, government-produced film that aired on public access television. It begins by recounting the mythical origins of the indigenous people of Mexico (all absurdly identified with the Aztecs), before narrating their fateful defeat by foreigners and, skipping over three centuries of Spanish monarchy, the rise of the modern state. Thus, it shifts from terrible conquest to glorious independence. This, then, makes sense of it. The official line is to celebrate the independence not of Mexico as such, but of a Mexico that seeks to resume the Aztec past.

The Autumnal months are full of dates marking that early encounter between worlds. After September, October follows with Columbus Day in the States, celebrated on the 11th, and what many Spanish-speaking countries call the day of Hispanidad on the 12th, commemorating the end of Columbus’ first transatlantic voyage (as well as Spain’s patron Virgin), which happens to fall near the October 7th anniversary of the Battle of Lepanto. Adding layers to this crowded month, the 11th is now also Indigenous People’s Day. To mark the occasion, Spain’s postmodern-leftist party Podemos took to spreading the hashtag “nothing to celebrate,” maintaining that European involvement in the New World has consisted chiefly of despotic bloodlust. Indeed, one of this party’s principal thinkers, Carlos Monedero, recently travelled to Mexico, where he asked forgiveness on behalf of his country (allowing himself to briefly, and uncharacteristically, identify with its history). In this, he was obliging the Mexican President, Mr. Obrador, who, speaking for Moctezuma’s vacant throne, had asked both Spain and the Church to apologize. Finally, the fall commemorations concluded with November’s Thanksgiving controversy.

Now, as we enter December, all our threads might just come together, for in this month we remember a humble man of the Mexica, St. Cuauhtlahtoatzin. His name means “Speaks like an Eagle,” and it is his story that will explain the Mexican Madonna’s presence in Genoa, and perhaps bridge that divide some seem so keen to exploit.

Born in Aztec country, he lived through transformative times. The lavish diet of the gods had ended. History forces us to fathom the slaughter of tens of thousands of human cattle each year. Indeed, the number of people sacrificed during the inauguration of the main pyramid at the imperial capital apparently exceeded 80,000. The event lasted four days and nights, and was presided over by an elderly man, the enigmatic Tlacaelel. It was his devotion to the gods that spurred on this impressive bureaucracy of blood. At the time of this festival of gore, Speaks Like an Eagle was around thirteen years old, but being a peasant’s son, he would not have attended the spectacle, which was reserved for nobility.

Yes, that was over now. A coalition of local tribes and Spaniards had seen to it. Yet, in spite of the lack of victims, the sun still rose. The god of that heavenly light was not, apparently, in need of hearts to keep its fire burning. The same was true of the other blood-drinking deities and the natural processes they had, by way of oracular priests, claimed to preside over. The earth was still underfoot. Day still followed night. Rain still rained and the crops still grew. It is in this context that many natives were embracing the religion of the newcomers, under whose sign our peasant’s son was baptized by the name of Juan Diego. And if that religion was still ‘of the newcomers,’ it would soon belong equally to his people.

Believers say that this future saint was already in his fifties when something extraordinary happened. One December 9th while walking near the foot of Tepeyac hill, he was visited by a young woman speaking his native tongue, who revealed that she was the Virgin Mary. She would appear to him several more times after this, and although the visionary peasant was able to contact the bishop of Mexico, don Juan de Zumárraga, he was not at first taken seriously. Then, on December 12th, after healing his uncle from what had seemed like a fatal illness, the Virgin bid Juan Diego to climb a hill and collect the flowers that were blooming there despite the Mexican winter. These were strange flowers, for they were European, but had apparently found fertile ground on American soil.

He brought the petalled bounty down, bundled in his cloak, a peasant’s garb called a tilma. She rearranged them and told him to once more go to the bishop. Gaining an audience the very next day, Juan opened his tilma before the clergyman, whereupon the flowers fell to the ground, and an image of the Virgin appeared on the cloak. Zumárraga would go on to produce a full account of the apparition, now lost, which was kept at the archdiocese of Mexico City (at least until 1601), and we have reports of it at the Franciscan monastery of Vitoria, in Spain. We also have a letter of the bishop to Hernán Cortés that seems to allude to the event.

“La Virgen de Guadalupe” (1691), a 181×123 cm oil on canvas by Manuel de Arellano (1662-1722) and Antonio de Arellano (1638-1714). Juan Diego’s encounters with the Virgin Mary and his presentation of the tilma to the bishop are depicted in the corners of the painting.

PHOTO: LOS ANGELES COUNTY MUSEUM OF ART.

Preserved to this day, the figure is considered miraculous, with its composition remaining a mystery. It has survived several destructive episodes, including an explosion that damaged much of the basilica in which it is kept, even contorting a metal crucifix whose presence continues to serve as a reminder of the attack. The events leading to the veneration of the tilma image are recounted in the Nican Mopohua, “Thus it is Told,” a work written in the local Nahuatl language and published in 1649 (a Spanish translation would come much later). Native culture did not cease with the coming of the Europeans, and this testament of poetic prose, telling the story of the earliest indigenous Christian saint, is surely one of its enduring legacies.

We have already mentioned that this apparition shares her name with another Lady of Guadalupe. The latter is a region in Spain that has long held to its own Marian icon of veneration, and was also Hernán Cortés’s native land. This seems to have been a readily available (and, for Spaniards, pronounceable), homophonous adaptation of the native title heard by Juan Diego, Tequatlasupe, or “She who crushes the Serpent.” The name, then, provides a semantic bridge with Spain. Apart from her title, Our Lady Serpent-Crusher’s image dons numerous native symbols: the black ribbon worn during pregnancy by Mexica women, combined with unbundled hair, conveys both pregnancy and maidenhood. Her clothes are decorated with the Nahui Ollin, a four-petalled flower representing the mythical Fifth Sun, indicating that the expected, yet feared, coming of the Age of the Fifth Sun was to be fulfilled in the child she bore. The same symbol apparently also represented Ometeolt, the first god in Aztec cosmology, so that the true meaning of that deity was being made manifest through this pregnant woman. Indeed, these four petals cannot but remind us of the arms of the cross.

Furthermore, her feet rest upon a crescent moon, a Biblical image that also bears local resonance, given that Mexico means “center of the moon.” Below the moon, is a cherub whose face and hair are those of a mature man, wearing a shirt typical of native converts, with eagle wings – an image, it seems, of Speaks like an Eagle. With one arm he holds the lower edge of the Virgin’s mantle, on which we see the stars, and with the other he supports her tunic, on which appear the flowers. Starry mantle and flowered tunic would represent sky and earth united by sainthood. Eventually, this apparition was declared patroness of all the Americas.

Now we know her origin, but how did she come to Europe? It happened by request of Mexico’s second bishop, Alonso Montúfar, who had a reproduction made of the tilma. This he touched to the original, sending the replica across the Atlantic as a gift to Philip II of Spain, who gave it to his brother, Don John of Austria. Don John in turn bestowed it on a certain Andrea Doria, with whom he was organizing the Holy League’s forces to defend Europe against ongoing Ottoman expansion.

During the 1571 battle of Lepanto, Spaniards, Italians, and assorted Christians faced off against Turkish power on the Mediterranean in a contest to decide who would rightfully call it the Mare Nostrum (Our Sea). Doria had the image placed in his vessel’s chapel. During the battle, overwhelmed by enemy ships, he prayed for the Virgin’s intercession, whereupon a storm dispersed the opposing fleet. Consequently, thousands of Christians were liberated from the captured vessels in which they labored. Pope Pius V had asked the faithful to pray the rosary that the League might triumph, and so he dedicated October 7th to Our Lady of Victory (again, October is a full month). The image of the tilma, with its Mesoamerican symbols, became an heirloom of the Doria family, and it is through them that it came to rest in Genoa, as a donation to the church. Just as Juan Diego found European flowers in Mexico, Europeans may now behold the Mexican four-petaled flower adorning an Italian shrine.

That which had represented a blessing of indigenous culture, Christianity’s arrival not as foreign import, but falling on the people from above, was now connected to Europe’s own preservation from foreign domination. We might say that the New World (old as the Old one) came to Europe’s aid that day. So defeated was the Aztec empire, that its symbols—now resurrected as Christian symbols—had become victorious in the lands of its foreign conqueror. So conquered was Mexico, that Mexican images now stood triumphant in battles across the ocean. We have here a figure for the ideal of Evangelization: To be humbled is to be exalted. Or, in more secular terms, not everything should be thought of as oppressed or oppressor.

Today, however, the secret symmetries of history are forgotten in favor of stoking resentment. Whereas the Lady of Guadalupe was taken for their standard by the leaders of the 1810 revolt against the Spanish that eventually led to independence, Mexico’s political class has long favoured a sort of Aztec aesthetic, Moctezuma-kitsch as its founding myth. We might speculate that a political establishment, educational curriculum, and mainstream media willing to celebrate a cannibalistic theocracy as Mexico’s identity have contributed to the occult revival around images of death practiced today, often inspiring the devotion of the narco-cartels, although by no means limited to them.

This is a warning to us as well—it’s dangerous business to invoke the past. We should not react reflexively to the demagoguery of those who would defame our history. I do not object to combining Columbus/Hispanidad Day with a celebration of indigenous people in former European colonies and overseas territories, fully recognizing the bad—as well as the good—that took place. But instead of resenting others or ourselves, why not consider where the strands meet, why not look for patterns of reconciliation? We might reflect, for example, on the remarkable set of events that led to the presence of the Nahui Ollin on the waters of the Mediterranean, riding victorious ships at Lepanto. And if October has become crowded with the clumsy politics of confrontation, we might escape to Juan Diego’s feast day of December 9th and the Lady’s commemoration on the 12th. We might take from these their reconciling balm, their celebration of the native peoples of the Americas and, for our part, here on the eastern shores of the Atlantic, their links to a Europe triumphant.

Editor’s Note: The Battle of Lepanto was featured in Issue 20 of our print edition. Two pieces from that edition are available on our website: Lepanto, 450 Years Later: Hope for Christendom in Crisis by Imre von Habsburg-Lothringen and Saint Pius V, the Pope of Lepanto by Roberto de Mattei.