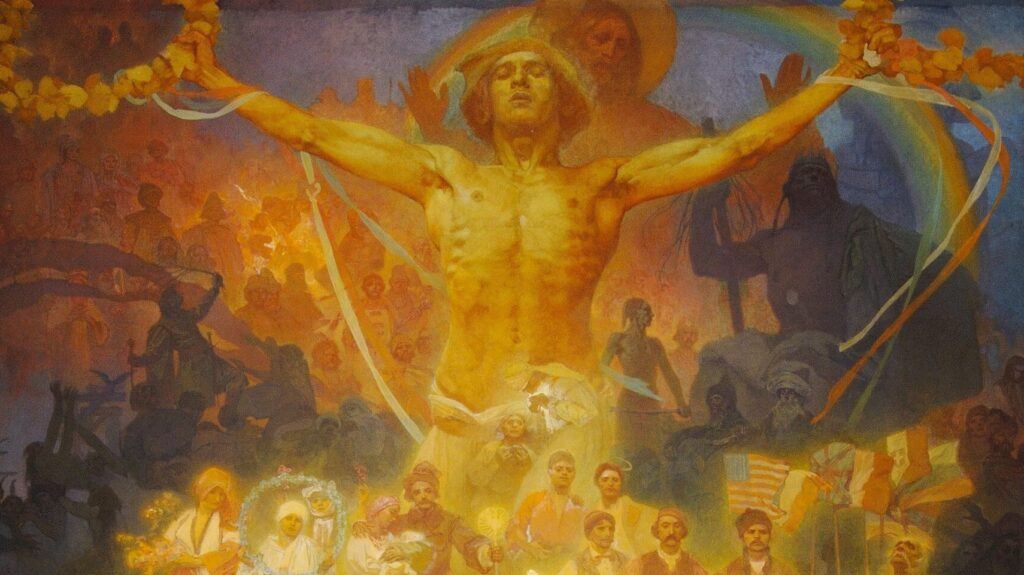

“The Slav Epic cycle No.20: Apotheosis: Slavs for Humanity.” (1918) Four Stages of Slav History in Four Colours. Oil on canvas by Alphons Maria Mucha (1860-1939), located in Moravský Krumlov, Moravia region, Czech Republic.

When defending nationhood, or the distinctiveness of cultures and identities, we sometimes find ourselves hindered by an excessively utilitarian approach. Defenders of ‘the nation’ refer to the practical manageability of smaller scale systems; how a plurality of sovereign states can produce a balance of power serving as a bulwark against hegemony; the moral superiority of a certain culture as necessitating that its heirs prevail in a given polity, and so on.

In all this, it often goes unremarked that the diversity of nations as such is an aesthetic good. Even when the latter is asserted, it usually does not tap the vast tradition underlying this position, a tradition with its roots in Plato and the Bible, which understands diversity as an occasion for contemplating the oneness of God.

The Biblical division of humanity into nations (Genesis 9 and 10; Jubilees 8 and 9) consists of 70 or 72 people-groups descending from the three sons of Noah. This occurs before the confusion of tongues at Babel and is not presented as a safeguard against hubris but as a regenerative labor following the flood.

The descendants of Noah acting as patriarchs to the nations would themselves correspond to tutelary angelic administrators. According to the Dead Sea Scrolls, specifically the version of Deuteronomy (32:8-9) found at Qumran in Palestine, these nations correspond to the angels or “children of El [God],”

When the Most High divided to the nations their inheritance, When he separated the sons of Adam, He set the bounds of the people according to the number of the children of El. For the LORD’s portion is his people; Jacob is the lot of his inheritance.

This tradition is also Ugaritic, with ancient Canaanite religion ascribing 70 children to the supreme deity. The paganising error of describing metaphysical principles (the ‘names’ of God) and angelic intelligences as “offspring” of God (whose implication can be taken to be that they are the same species and therefore somehow ontologically equivalent to Him) was corrected by the neo-Platonic philosophical tradition and mainstream theological currents. The Septuagint Bible, therefore, tells us that God “set the bounds of the nations according to the number of the angels of God.” Ultimately, according to Christianity, the angelic function is assimilated to humanity, such that, in the course of history, nations and other collectivities receive patron saints.

Other mainstream versions of Deuteronomy somewhat awkwardly feature the expression “children of Israel” rather than of El, but this is no great difficulty, as the passage would then be making Israel a microcosm of the total human ecumene descending from Adam. Indeed, the twelve tribes of Israel correspond to seventy-two nations, given that both are the ‘kissing numbers’ of spheres: twelve (three-dimensional) spheres can simultaneously touch a central (thirteenth) sphere of their same size, just as seventy-two (sixth-dimensional) spheres can touch a central (seventy-third) sphere of their same size. The principle is that of ordered multiplicity, albeit at different dimensions, which, in Biblical symbolism, relates to different scales, from the nation of Israel to the whole Adamic family. I have not encountered this approach to the Bible’s use of numbers elsewhere, but would argue for its appropriateness.

In Jewish tradition, we find that these ‘children’ correspond to the Kabbalah’s seventy-two letters of the name of God (the Shemhamphorasch), also manifesting as the seventy-two wings of the angel Metatron.

The above is compatible with Plato’s account of the origin of nations in Critias:

At one time, the gods received their due portions over the entire earth, region by region—and without strife … as they received what was naturally theirs in the allotment of justice, they began to settle their lands … they did not compel us by exerting bodily force on our bodies … but rather … they directed us from the stern, as if they were applying to the soul the rudder of Persuasion … as the gods received their various regions lot by lot, they began to improve their possessions.

And in The Laws,

So Cronus … who was well-disposed to man … placed us in the care of the spirits, a superior order of beings, who were to look after our interests … the result of their attentions was peace, respect for others, good laws, justice in full measure, and a state of happiness and harmony among the races of the world.

Given neo-Platonic exegesis concerning the gods, nations would correspond to necessary, higher-order realities manifesting the ineffable character of God (Platonism’s “The One”).

The notion that human differentiation occurs according to an archetypal pattern conforming to a Divine blueprint—God’s disclosure of His names—occurs in the work of Church Father St. Dionysus (The Celestial Hierarchy):

The Word of God has assigned our Hierarchy to Angels, by naming Michael as Ruler of the Jewish people, and others over other nations. For the Most High established borders of nations according to the number of Angels of God. (IX:2)

The idea that God’s oneness manifests a harmony (of diverse forms) implies equality. No single created form is an exhaustive icon of God, as St. Thomas Aquinas puts it, “creatures cannot attain to any perfect likeness of God so long as they are confined to one species of creature.” Part of their iconic function is to represent God’s unity through their harmony (peaceful relations between plural forms), because underlying oneness is disclosed by harmony, rather than discord. St. Thomas continues: “Multiplicity therefore, and variety, was needful in the creation.” The concept is also found in the Qur’an (30:22): “And one of His signs is the creation of the heavens and the earth, and the diversity of your languages and colours. Surely in this are signs for those of sound knowledge.”

An abstract principle must display itself through many practices, otherwise, its character will be restricted to that of one possible manifestation only. St. Thomas continues: “If any agent whose power extends to various effects were to produce only one of those effects, his power would not be so completely reduced to actuality [manifest in the world] as by making many.” In fact, not only must the world consist of not one, but many, forms, it must also consist of many types of form:

The multiplication of species is a greater addition to the good of the universe than the multiplication of individuals of a single species. The perfection of the universe therefore requires not only a multitude of individuals, but also diverse kinds, and therefore diverse grades of things.

Making the exact same point, in proposition twenty-one of the Metaphysical Elements, Proclus explains how that which constitutes the common feature of a set of forms (circularity in the case of differently-coloured circles) does not itself proceed from one of these (it isn’t the red circle that originates the shape which it shares with a yellow one). Rather, the common feature is prior to, and encompassing of, the set of forms. A principle cannot be restricted to one of its expressions over and against the others (circles are not ideally red rather than yellow, language is not ideally Mongolian rather than Swahili):

In each order … there is one monad prior to the multitude, which imparts one ratio and connection to the natures arranged in it, both to each other and to the whole … that which ranks as the cause of the one series must necessarily be prior to all in that series, and all things must be generated by it as coordinate.

This idea of necessarily diverse forms being equal in their common display of the creativity of Divine oneness also occurs in the Qur’an (49:13): “O mankind, indeed We have created you from male and female and made you peoples and tribes that you may know one another. Indeed, the most noble of you in the sight of Allah is the most righteous.”

The fact that one form within a set may happen to express that common feature more perfectly than others (like the nation of Israel compared to gentile nations), is an accidental rather than an essential feature. Writes St. Dionysus:

But if any one should say, ‘How then were the people of the Hebrews alone conducted to the supremely Divine illuminations?’ we must answer, that we ought not to throw the blame of the other nations wandering after those which are no gods upon the direct guidance of the Angels, but that they themselves, by their own declension, fell away from the direct leading towards the Divine Being, through self-conceit and self-will, and through their irrational veneration for things which appeared to them worthy of God. (IX:3)

Therefore, the election of Israel is owing to the fact that “Israel [Jacob] elected himself for the worship of the true God,” whereas others turned away, but it was “assigned equally with the other nations, to one of the holy Angels,” and “there is one Providence of the whole, superessentially established above all … the Angels who preside over each nation, elevate, as far as possible, those who follow them with a willing mind.”

Christian theologians have proposed that the angelic fall from Heaven implies a process whereby national, tutelary angels accepted worship from their wards, becoming corrupt and leading the nations under their care into apostasy. This would have been rectified by conversion to Christianity.

In contrast, the design represented by St. Dionysus recognizes that the “higher-order realities” that those angels correspond to are not themselves corruptible. We may therefore read the Bible as implying that people went astray by worshiping other than God, whereupon unclean spirits interposed themselves between them and their rightful angelic guides. The traditional Christian notion that pagan gods are demons is thus retained without imputing sin upon angelic stewards.

In line with this, the Qur’an seems to attribute the actions of Biblical fallen angels, including their joining with human females (72:6) and sowing corruption (6:4), to the jinn (spirits), rather than to angels. Whereas the jinn had previously enjoyed access to prophetic or angelic stations, they subsequently lost this access (72:9), and so can be said to have fallen.

The idea of nations corrupting their angels was taken a step further by Origen of Alexandria, who maintained that spiritual corruption led to the emergence of distinct nations in the first place, whereupon angelic guidance was made necessary. Origen suggests that Israel never had any need of such guidance, and remained under the direct instruction of God, without a mediating angel.

Ultimately, any true religion is under the “direct instruction of God,” where all mediation is a display of His creative power and not an object between Him and us (as though God were a cause in a series of causes and effects). It is in these terms that traditional language concerning God as the only agent, and intermediation as unnecessary, should be approached, (and accounts of God acting ‘directly’ remind us that He can always choose to produce a sui generis cause).

But Origen’s argument reifies this idea. Plurality (of causes in time, and of nations in space) becomes an evil that opposes God’s unity. The problem with this view is that it is, ultimately, a world-denying rejection of creation itself (ironically given Origen’s refutations of dualistic, “gnostic” heresy). Jean Danielou explains:

The political order dependent on the existence of a variety of nations … was henceforth over and done with … [Origen] regarded polyarchy as a system going with polytheism … Monarchy [one state over all humanity] was to appear at the end of the world.

The monotony of monarchy here includes cultural homogenization, for Origen seems to consider the contingent features associated with the nation of Israel, including the Hebrew language, as constituting the ideal character of humanity.

Concerning this flawed metaphysics in Origen and the contrasting medieval conception, Arthur Lovejoy writes that:

Origen had, in connection with his doctrine of the pre-existence of souls, declared that God’s goodness had been shown at the first creation by making all creatures alike spiritual and rational, and that the existing inequalities among them were results of their differing use of their freedom of choice. This opinion Aquinas declares to be manifestly false. ‘The best thing in creation is the perfection of the universe, which consists in the orderly variety of things … Thus the diversity of creatures does not arise from diversity of merits, but was primarily intended by the prime agent.’ The proof offered for this is the more striking because of the contrast between its highly scholastic method and the revolutionary implications which were latent in it.

God’s unity cannot be identified with a created uniformity, for no created form can express that unity better than some other conceivable equivalent form. Equally perfect equivalent forms are always possible; a panther is as much a feline as a tiger; circularity will only ever appear in specific circles, whose substance (crayon on a page, light on a screen, etc.) is always accidental vis the definition of a circle itself. Nicholas of Cusa encapsulates the point in De Pace Fidei’s aphoristic “Equality is the unfolding of form in oneness.”

In order to avoid idolatrous identification of God with His creation, therefore, we should favor diversity: I observe that circularity is that which many different-colored circles have in common, without the definition of a circle including reference to color.

Thus do we find that the world consists of “joints,” as Plato taught; borders between forms and categories of forms. If all circles were continuous with each other, none of them would be a circle, their outlines must be discontinuous for them to all manifest that common shape. They must each be themselves in order to all be alike.

To bind a thing up is to express its universal character. We can think of ‘beauty’. I cannot make a painting beautiful unless I perfect its specific beauty, rather than imitating the beauty of myriad things. A race horse, a sunset, a woman, are all beautiful, but they are also quite distinct. Apart from more practical considerations, therefore, projects such as the development of a culture and identity (and Ortega y Gasset’s “enticing project for a life in common” that every nation must define for itself) have need of borders for the same reason.

Arthur Lovejoy summarizes the point: “A universe that is ‘full, in the sense of exhibiting the maximal diversity of kinds, must be chiefly full of ‘leaps.’ There is at every point an abrupt passage to something different.”

Crucially, given that no differentiation can occur as a consequence of pure accident, but must draw on God’s design, whether we attend to some abstract category (like a “shape,” “circle”) or to its tangible instances (like the different colors of specific circles in the world), we will be dealing with necessary, higher-order realities. Both genus and differentia manifest archetypes. Blue is no less an archetype than circle. A pyramid does not cause us to contemplate God only by implying a perfect, singular point at its peak, but also by implying the potentially infinite extension of its base. Therefore: diversity reminds us that God is transcendent, for no particular form can express Him, and that God is present, for all particular forms express Him.

The two ideas above, namely that equivalent forms are always possible (for no one form can exhaust God’s disclosure of Himself) and that any authentic differentiating feature results from His disclosures (for nothing exists apart from God’s Being) are expressed by Nicholas of Cusa in the following passage from On Learned Ignorance:

All the names are unfolding of the enfolding of the one, ineffable name, and as this proper name is infinite, so it enfolds an infinite number of such names of particular perfections. Although there could be many such unfoldings, they are never so many or so great that there could not be more; each of them is to the proper and ineffable name what the finite is to the infinite.

He precisely applies this principle to national diversity. As Michael Harrington observes in Sacred Place in Early Medieval Neoplatonism, Nicholas “had long thought of the division of human beings into distinct regions and nations as an important stimulus to world harmony.” Thus, “following both Eckhart and the humanists,” and, we would add, St. Dionysus,

[Nicholas] was able to assess the diversity of human languages non-instrumentally and positively as the different ‘points of view’ of an ‘explicating’ and always partial human reason.

Therefore, Nicholas had “no interest in a mystical ursprache [original human speech] nor in a ‘natural’ and universal language.” We can apply this idea to cultural differences in general: There is no single cultural expression (linguistic or otherwise) that most perfectly captures the human condition and God’s design, over and against all possible alternatives.

So far we have established the positive, archetypal character of national diversity. We may now contrast this against the well-established view that the existence of nations is, at worst, a tragic necessity, a bulwark against worse things, or at best, an accidental feature of life.

Because the modern mind does not believe in archetypal disclosure (‘names’ of God) it understands diversity as resulting from random, chaotic processes. It therefore posits that stability may be guaranteed by balancing the inherently contradicting interests of individuals and states (individualism or market-determinism, and statism or historical-determinism being the principal categories of political modernity).

Unfortunately, this view occurs in ‘traditional’ conservative thought as well. This is the case among Catholic thinkers, for example, to the degree that they have, sometimes unconsciously, accepted the idea that nature receives grace in an act which is extraneous to its character, being inherently devoid of grace, and that God could have chosen to create a world in which nature was never oriented towards salvation through grace. Such a view is sometimes described as “two-tier Thomism,” the bottom tier being pura natura, pure nature, and the top being grace (where “Thomism” does not necessarily correspond to St. Thomas’ actual thought).

Nature (analogous to differentia, substance, colors as distinct from shapes) would, in itself, have no depth-dimension, no archetypical resonances, and so, diversity would not be expressive of God’s names, being instead a chaotic flux, resulting from the fall.

It is for this reason that Catholic intellectuals will, at times, describe nations as a moral good in the accidental mode: it is a moral good to honor my parents, and it so happens that I have this particular mother and father. To the degree that this scales up to a nation, patriotism is an application thereof.

It is unclear why perpetuating cultural features honors one’s parents, however, for such honoring relates to a specific moral responsibility concerning their well-being. Our personal relationship and care-taking of our parents would seem to be distinct from the perpetuation of an intangible cultural legacy, however much the paradigm in question may want to assimilate the latter into the former. If culture has no verticality, no animating archetype, then the culture my parents happened to inhabit bears no moral significance. It is pure accident (part of a pure nature devoid of grace). They wore it the way they wore a particular shirt, but am I expected to dress in their clothes as well?

Apart from its flaccid account of nationhood, this view takes states to be a necessary restraint against disorder, and, if it justifies their diversity, it does so in liberal terms as a balance of power safeguarding against despotic hegemony.

This may be why many Catholic political theorists did not resist the destruction of the commons: if the individual is a moral agent and the state a moral restraint, the one’s private property and the other’s state property have their place in the economy of salvation. The commons, however, would be a field of chaotic, sinful desires and conflicting interests destined for tragedy. We are to restrain nature (including human nature), until it receives grace, rather than shepherding forth inherent archetypical realities by which the names of God might reveal themselves and magnetize us to proper worship.

The opposite perspective would champion economic arrangements that cultivate self-perpetuating, organic, virtuous sociability distinct from individual-level moral calculus and state administration.

To summarize, then: this understanding sees in the picturesque, coherent distinction of a nation and culture the occasion for contemplating the presence of God (his “names” and archetypical realities), and in the diversity of nations it finds occasion for contemplating His transcendence, which exceeds forms even as it draws them into a harmony expressive of oneness. As Proclus puts it, what diverse forms have in common is imparted “both to each other and to the whole.” Nations, therefore, must express universal virtues like justice, order, and sociability within and between themselves; they must constitute both coherent wholes in themselves and a communal harmony together.

If the integrity of a nation manifests God’s oneness in the mode of presence, the interaction of nations manifests it in the mode of transcendence.

Nations are necessarily loci of political participation, and it is likewise legitimate for groups of nations with something in common (and, indeed, in a final instance, the whole of humanity) to share political institutions. The form this takes should vary depending on historical conditions, but we may seek guidance in Plato’s move towards what we might describe as a Hellenic federation, a virtuous equivalent to the yoke of that Persian conquest whose tyranny the Athenian precisely criticizes in The Laws for its vicious effacement of the distinction of peoples, but whose imperial imperative can be imitated in an organic form.