Moorland Landscape with Rainstorm (1751), a 30.3 x 42.3 cm oil on canvas by George Lambert (1700-1765), located at the Tate Britain, London

Attempting to expound someone else’s thought is always a high-risk endeavor. But since I recently declared Dalmacio Negro Pavón the most significant political thinker in Spain in recent decades, with all due caution, I will outline what I consider to be some of the interpretive keys to Negro Pavón’s thought.

Each year, 80,000 literary pilgrims make the trek into Brontë country in West Yorkshire. If you go by car, you emerge out of the sheep-spotted emerald dales to see the rugged, rusty-colored moors suddenly sweeping up from the road, which climbs steadily towards a little village. There, three sisters, none of whom would survive their father or see their fortieth birthday, wrote some of the greatest classics penned on English soil. Haworth is a village of less than 7,000, a captivating confusion of stone bridges, brick houses, and narrow streets first mentioned in 1209 but dating from much earlier. The Haworth Parish Church is at least eight centuries old; Patrick Brontë was appointed curate in 1820.

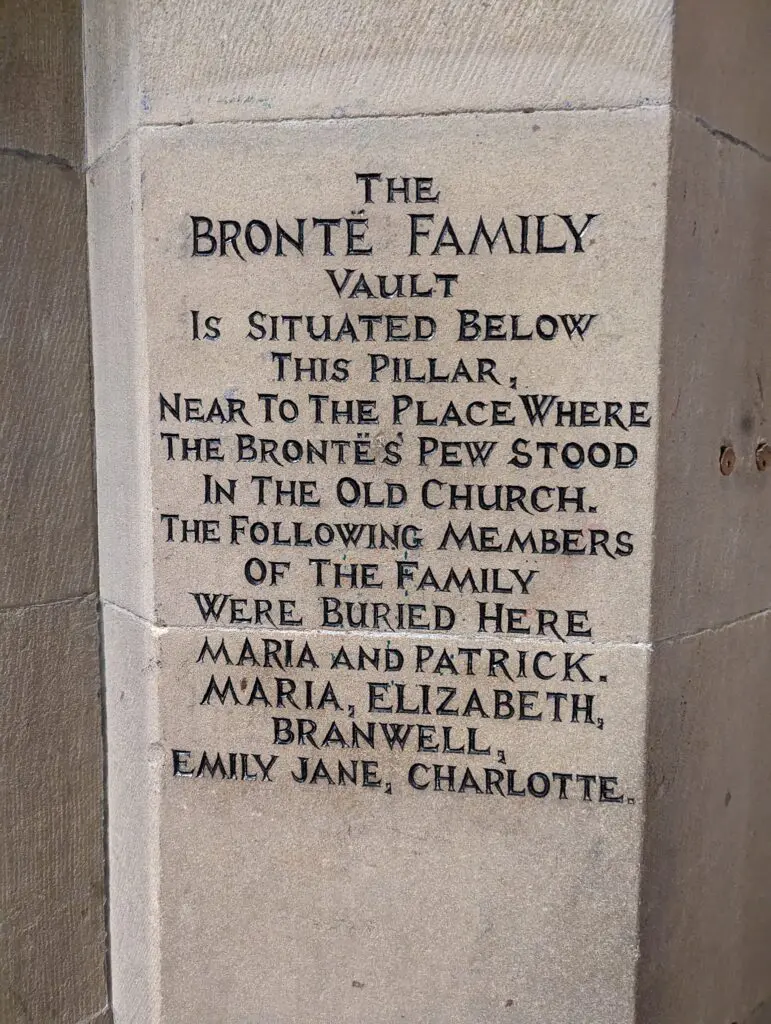

All the Brontës but Anne are buried beneath a pillar near the front of the church, which rises from the floor where the family pew used to stand (Anne died in Scarborough and is buried in the church there). Patrick buried his entire family here; just outside the grey stone church, the cemetery is crowded with topsy-turvy gravestones greened with moss and lichen. Many of the dates are faded; those discernable are very, very old. The church itself feels damp; on display inside the Brontë Memorial Chapel are the burial records for Haworth from 1848. Emily Jane Brontë, No. 1775, is the second last name recorded there. The text marking the family crypt is from Corinthians:

The sting of death which is sin, and the strength of sin is the law, but thanks be to God, which giveth us the victory through our Lord Jesus Christ.

Much has been made of the tragic lives of the Brontë children, but it was perhaps their father who suffered most. Patrick was widowed in 1821 when his wife Maria died at the age of 38 of uterine cancer. Their two oldest daughters, Elizabeth and Maria, died of disease in 1825 at the ages of 10 and 11. The surviving children—Charlotte, Branwell, Emily, and Anne—were very close, spending much of their childhood developing imaginary worlds. Their childhood stories, recorded painstakingly in tiny handwriting, are now on display at the parsonage. Branwell initially showed promise as a writer but, to the despair of his family, took to drugs and drink, his addictions exacerbated by a turbulent affair with a married woman. He died of tuberculosis and self-abuse in 1848 at the age of 31.

By the time he died, his sisters were already famous authors, publishing novels and poetry under the male pseudonyms Currer (Charlotte), Ellis (Emily) and Acton (Anne) Bell, unbeknownst to Branwell. The sisters feared that their brother would be driven further into despair by their success; Charlotte wrote to her publisher that he had died without “ever knowing that his sisters had published a line.” Emily caught a cold at Branwell’s funeral and died of tuberculosis before the year was out; she never left the house again. Anne also died of tuberculosis the following year. Charlotte lived the longest, marrying one of her father’s curates, Arthur Bell Nichols, in 1854, but died with their unborn child at age 38 in March 1855 of pregnancy complications that would be treatable today. Patrick was left bereft.

The beauty and brevity of the Brontë phenomenon captured the public imagination immediately. Several years ago, I purchased a copy of Harper’s Weekly published two years after Charlotte’s death on 16 May 1857, containing an essay titled “Currer Bell and Her Sisters.” It began: “Let us look into the Haworth parsonage at the close of the year 1846. Charlotte Brontë is thirty years old, her sisters three and six years younger. The father is threescore-and-ten, and almost blind. Branwell is a habitual drunkard, and an opium-eater.” The report describes Branwell asking to be raised to his feet as death approached: “So it was done; and he fronted the King of Terrors standing … ‘He is in God’s hand,’ wrote Charlotte, ‘And the All-Powerful is likewise All-Merciful.’”

Charlotte’s death is also described. At one point in her brief illness, she awoke to find her husband bending over her, praying fervently: “’Oh,’ she whispered, ’I am not going to die, am I? He will not separate us; we have been so happy.’ But her earthly days were numbered, and on the last day of March 1855, passing from that old gray parsonage amidst the wild moors, she entered the glories of the celestial city. On Easter Sunday, all that was mortal of Currer Bell was committed to dust in the sure hope of the resurrection to eternal life through our Lord Jesus Christ.”

The heartbroken Patrick instigated an investigation into the health conditions of Haworth village. It was conducted by Benjamin Babbage, who found that decomposition from the overpacked graveyard was leaching into the village water supply; the dead were poisoning the living. The effect on the villagers’ health was devastating: 41.6% of Haworth’s inhabitants died before the age of 6, and the average age of death was just shy of 26. This was high even for Victorian England, where those who survived into adulthood were expected to attain a relatively old age. For over a hundred years, readers have wondered: what might the sisters have done with a little more time?

Today, Haworth Parsonage is one of the few historical tourist traps that still feels ancient. Climbing the steps to the black front doors that overlook the graveyard, it seems precisely the sort of place where one would imagine great novels, loaded with darkness, being written. Just inside the door on the left is the study where much of the Brontë canon—including Jane Eyre (Charlotte), Wuthering Heights (Emily), and The Tenant of Wildfell Hall (Anne) were penned. The parsonage hosted an eruption of genius that entrances all who encounter it; Patrick was unaware that, while he faithfully went about the work of a country parson, London’s literary scene was captivated by the works of Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell—written by his daughters in the room across from his study.

The room where the Brontës wrote is laid out as if they’d just left, with papers and writing utensils on the table in front of the fireplace. A large portrait of Charlotte hangs above the mantel. It is the room where it all happened, and it is hard not to gape. Based on the bulging eyes of other tourists clustering around the doors, I was not the only one who felt that way. Patrick’s studies and the bedrooms have all been reconstructed, as well. The chaos of Branwell’s bedroom leading up to his death has been recreated, with papers scattered everywhere, discarded liquor bottles, and a turbulent bed. Display cases upstairs hold dozens of handwritten letters, drafts, and drawings by the Brontës; even a few hours barely brushes the surface of what the curators have gathered in the parsonage.

More than a century and a half on, the Brontës are still all the rage. Letters signed by Charlotte, for example, frequently realize up to £50,000 at auction. New Brontë artifacts—and surely there cannot be more?—are treated as groundbreaking discoveries, such as a ring engraved with her name and containing a braided lock of her hair, which surfaced on Antiques Roadshow in 2019 and was priced at £20,000. The long-lost Honresfield library, collected by the Law family, contains a wealth of Brontë manuscripts (it also contains works by Jane Austen, Sir Walter Scott, and Robert Burns) including 31 poems handwritten by Emily with marginal notes by Charlotte—sold recently for $20 million to collaborating British institutions after a campaign to prevent the works from falling into private hands. One of the books, a tiny manuscript by 13-year-old Charlotte, cost $1.25 million. It was promptly sent to Haworth Parsonage, where it can be seen today.

Haworth Parsonage has now been a place of literary pilgrimage for over 170 years. The 1857 story in Harper’s Weekly closed by reminding readers that there was one Brontë yet living. “The childless father—an old man of more than fourscore—still for a brief space remains in the old parsonage, begirt by the grave-yard in which have been laid all save himself of that household and who had come thither a full generation before.” As the fame of his deceased daughters grew, Rev. Patrick Brontë patiently bore the attentions of legions of readers who came to the parsonage to see where his girls had written their masterpieces and to gawk at him, the only survivor of what was arguably England’s most magnificent literary family. He died four years after the article was published, in 1861. The visitors have not stopped since then, and I am glad that I joined them. Haworth is a haunting, beautiful place.

Standing in the front hall of the parsonage, looking into the writing room, it was easy to imagine Emily Brontë picking up a pen, dipping into an inkpot, and writing the first lines of Wuthering Heights: “I have dreamt in my life, dreams that have stayed with me ever after, and changed my ideas; they have gone through and through me, like wine through water, and altered the color of my mind. And this is one: I’m going to tell it—but take care not to smile at any part of it.”