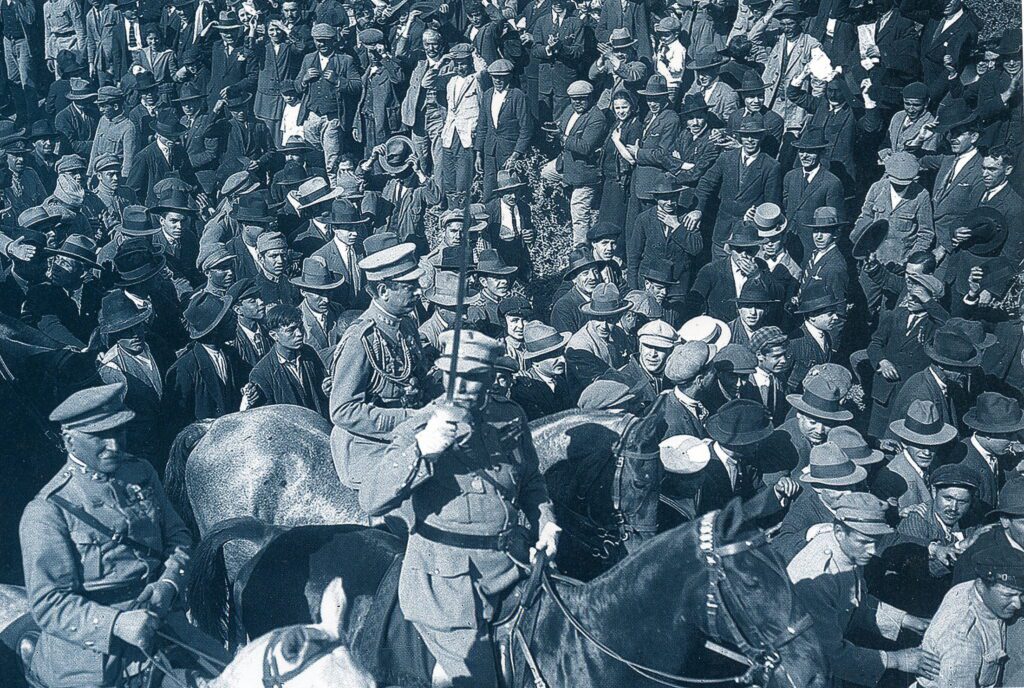

Military procession of General Gomes da Costa and his troops after the 28 May 1926 Revolution.

Attempting to expound someone else’s thought is always a high-risk endeavor. But since I recently declared Dalmacio Negro Pavón the most significant political thinker in Spain in recent decades, with all due caution, I will outline what I consider to be some of the interpretive keys to Negro Pavón’s thought.

The work of Dalmacio Negro Pavón reveals that politics cannot be understood without anthropology: the various conceptions of humanity throughout history are not mere theories but paradigms that have shaped the lives of peoples and conditioned political thought.

On the 28th of May of 1926, a military revolt began in Braga, a city in northern Portugal. It took only a few days for this uprising to overthrow the democratic First Republic and establish a nationalist military dictatorship, which lasted until 1933. This was soon followed by Salazar’s national-authoritarian regime of the Estado Novo which lasted until the Carnation Revolution of April 1974. But today we remember the ‘National Revolution’ and everything it ushered in.

The military revolt 97 years ago was engineered by young officers, captains, and lieutenants of the Portuguese armed forces—but was led by General Gomes da Costa, a veteran of the colonial wars in Africa and commander of the Portuguese Expeditionary Corps (CEP) in Flanders during the Great War.

At the time, the military was deeply influenced by the many political upheavals that had occurred in modern Portugal. They remembered the demise of the Portuguese Ancien Régime in 1820; the victory of the liberals during the Civil War of 1828-1834; the ‘Regeneration’ movement of 1851.

They also had in mind the uprising of 1910, a rebellion led by military and armed civilians commanded by Machado Santos, a junior Naval officer with ties to the Freemasons and the revolutionary secret society Carbonaria. It was the military’s outright neutrality at the time that allowed the rebels to succeed and proclaim the Republic. And when the rebels bombarded the Palácio das Necessidades during the revolution of 5 October 1910, a young King Manuel II was forced to flee while the army did nothing.

(This was not the first time Portugal’s royal family had been attacked by rebels. Two years earlier, in February 1908, Manuel’s father, King Carlos I, and his brother, Crown Prince Luís Filipe, had been murdered by Republican radicals belonging to the Carbonarians. The two murderers—Alfredo Costa and Manuel Buíça—were fanatic and committed rebels and were eventually killed by the king’s guards.)

The young members of the armed forces leading the 1926 National Revolution also had vividly in mind the chaos and violence of the 16 years period of the First Republic. From its very first days, the country was dominated by the Portuguese Republican Party (PRP, which was inspired by the jacobinism and radicalism of the Third French Republic). Its main enemy was the Catholic Church. The PRP’s leader, Afonso Costa, had even declared that he hoped to wipe out Catholicism completely from Portugal within one or two generations.

In February 1912, however, more moderate elements of the PRP split, forming the Unionist Party, led by Brito Camacho, and the Evolutionist Party, led by António José de Almeida. Still, Afonso Costa’s allies—known as ‘the Democrats’—dominated public life during those chaotic 16 years of the Portuguese First Republic (during which there were 46 governments).

In theory, the First Republic was a democracy, although only 7% of the population voted. Additionally, suffrage was restricted to men. (Costa didn’t want women to vote because he thought they were all under the influence of Catholic priests.) Monarchists and Catholics, as well as the syndicalist Left and even conservative Republicans, were all arbitrarily arrested by Costa’s security forces.

Since the election was widely considered to have been fraudulent and voting systematically manipulated, the only way to change things was by force. There were initial attempts at a change made in 1915 by General Pimenta de Castro, who after he was put to power by a military coup, launched a ‘reconciliation programme.’ However, he was overthrown by a democratic counter-revolution, which left over a hundred dead and hundreds wounded in Lisbon. Finally, there was Sidonism, a movement of popular-conservative and authoritarian nationalism, led by the charismatic Major Sidónio Pais, who was assassinated by the Left in 1918, only a year after coming to power.

With control of the streets and the ballot box—resorting to violence ‘only when necessary’—the Democrats gradually isolated themselves from others. This led to a spate of failed military conspiracies and coup attempts. Until 1926.

The military uprising in Braga on 28th of May of 1926 was quickly and successively joined by other military units across the country. They triumphed in only a few days. And at first, in terms of party politics, there was a broad convergence of support for the new military dictatorship—from the monarchists and pro-fascist extreme Right to labour Left.

The real enemies at the time were ‘the politicians’—the political class, the ruling elites, of the Republic. Democracy, for the ordinary Portuguese citizen, was not a government of the people, by the people, and for the people, but of the Democrats, by the Democrats, and for the Democrats, in the name of the people.

The winning coalition was quite broad and had representatives among the military, nationalists, right-wingers, monarchists, conservative republicans, and even technocrats. A rapid succession of military leaders soon followed, a period of instability that only ended General Carmona, the future President of the Republic.

Those who had the real command of the military dictatorship formed a nucleus of a few hundred officers—lieutenants, captains, and majors—who set the direction of what came to be called the National Revolution and acted as the ‘king-makers.’ They didn’t quite know what they wanted, but they certainly knew what they didn’t want: they wanted to avoid the problems seen elsewhere in postwar Europe, which was a place of growing radicalisation and constitutional crises, against a threatening backdrop of Communism. The only way to contain the radical Left at the time was through authoritarian right-wing movements and ‘states of exception.’

One of the problems faced by those who staged the National Revolution was dealing with the country’s chronic financial problems. To address this issue, the military brought in António de Oliveira Salazar, a professor of public finance from the University of Coimbra.

Salazar was an expert in public finance, but he had also studied political philosophy and had deep convictions. He was a committed Roman Catholic and his values and principles combined the doctrines of Leo XIII’s Catholic social teaching with the nationalist ‘reason of state’ thinking of Charles Maurras. Salazar was also an anthropological pessimist, who knew the history of Portugal well, and distrusted rhetoric and demagogy.

Named Minister of Finance in April 1928, Salazar controlled spending, balanced public accounts, and restored confidence. A few years later, with the Portuguese political scene in turmoil because of conflicting factions of radical nationalists and fascists on the Right, and those who wanted a return to constitutional republicanism without the dictatorship of the Democrats on the Left, a way out was found in Salazar.

Salazar’s solution was the Estado Novo—ideologically based on ‘God, country, family’—a form of conservative nationalism supported by the army and without political parties. It was, at the time of its proclamation in 1933, a solution situated at the centre of Portugal’s political spectrum, thus avoiding the extremes of Right and Left.

The Estado Novo became a conservative and authoritarian national regime. It was ideologically far removed from fascist totalitarianism and populism, although, in the 1930s and during the Spanish Civil War, it adopted some of the forms—and folklore—of the fascist movements.

During the Spanish Civil War, Salazar supported, in diplomatic terms and through propagandistic means, the cause of the Spanish rebel soldiers who, on 18 July 1936, rose up against the Popular Front government. Among the Nationalist anti-communist fighters, there were also many Portuguese volunteers, though they were not as numerous as the Italian or German contingents.

In World War II, Salazar opted for neutrality and came to an understanding with General Franco in Spain to help him keep Spain out of the conflict. The position of the two peninsular countries, historically and ideologically, could not have been more different. Portugal had a centuries-old alliance with Great Britain, based on convergent geopolitical interests of London and Lisbon, since Great Britain had always considered Portuguese independence essential to the balance of power in the European continent.

Spain, on the other hand, besides having greater historical affinities with the Axis powers, also had a greater ideological proximity to them. Franco could not forget the support that Hitler and Mussolini had provided during the Spanish Civil War, so he repaid his debt by sending the ‘Blue Division’ to fight alongside the Germans on the Eastern Front.

Despite these split loyalties, Salazar and Franco manoeuvred together to keep the Iberian Peninsula out of the war, knowing that if one was drawn into the conflict the other would necessarily follow.

In addition to foreign policy, the Estado Novo initiated a policy of public works in the 1930s. Portugal had not had public works since the last years of the monarchy. This policy—along with the negative experience of the democratic regime and the fact that Salazar spared the country from war—helped to maintain Salazar’s popularity among the urban middle classes, and the Catholic and conservative countryside, well until the mid-1950s.

Despite the authoritarian model pursued by Salazar, Portugal was a founding member of NATO, and a member of EFTA and other international organisations in Europe. Global acceptance of the Portuguese regime lasted until the end of the 1950s, when the colonial issue sparked a conflict between Portugal and the United Nations. Eventually, the Estado Novo was overthrown by a military coup in April 1974—a few years after Salazar’s death—and gave way to the Third Republic.

The military coup of April 1974 led to the traumatic decolonization of Portugal’s overseas territories, followed by long civil wars in Angola and Mozambique. On the continent, the coup gave way to a radical leftist wave that was only halted by a military intervention on the 25th of November, 1975, a kind of Thermidor that perpetuated the alternation in power between socialists and social democrats—a state of affairs that has characterized the governance of the country ever since.

Curiously, like the coup of 28 May 1926, the revolution of April 1974 was instigated by low-ranking military cadres—the so-called ‘April captains.’ They easily and swiftly put an end to a regime that was already in deep trouble—and which could no longer put up any serious resistance.