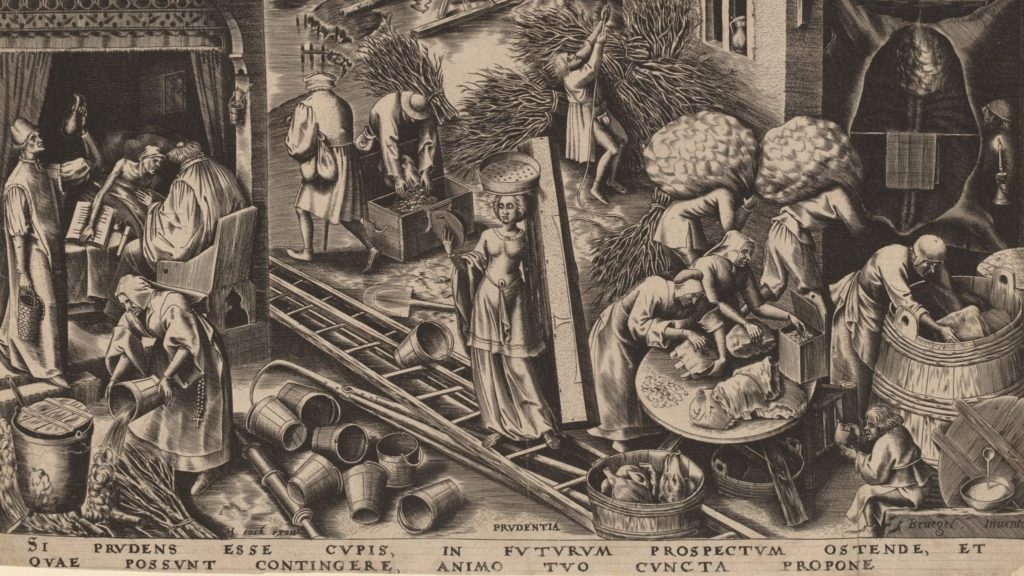

“Prudence” (1559) from a series of engravings “The Seven Virtues” by Philip Galle (1537-1612) after Pieter Bruegel the Elder, located in the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. The bottom caption reads: “SI PRVDENS ESSE CVPIS, IN FVTVRVM PROSPECTVM IN OSTENDE, ET / QVAE POSSVNT CONTINGERE, ANIMO TVO CVNCTA PROPONE.” (If you wish to be prudent, think always of the future and keep everything in the forefront of your mind.)

Attempting to expound someone else’s thought is always a high-risk endeavor. But since I recently declared Dalmacio Negro Pavón the most significant political thinker in Spain in recent decades, with all due caution, I will outline what I consider to be some of the interpretive keys to Negro Pavón’s thought.

As the Russian so-called ‘special military operation’ in the Ukraine entered its fourth month, Henry Kissinger, in a video link to the World Economic Forum in Davos, suggested that resolving the conflict “may require territorial adjustments.” Kissinger hoped that the Ukrainians would “match the heroism they have shown in the war with wisdom for the balance in Europe and the world at large.” Even the left leaning New York Times opined, on May 15, 2022, that Ukraine might have to make “painful territorial decisions” to achieve peace. Kissinger’s assessment also enjoyed support in a number of European capitals, from Paris and Berlin to Budapest. In a similar vein, the Pope felt that NATO might have “provoked” Russian aggression.

Elsewhere, such equivocation was not so well received. The Baltic states, Poland, and Ukraine itself found Kissinger’s opinion defeatist. Inna Sovsun, a deputy in the Ukrainian Assembly, considered his remarks “truly shameful,” whilst President Zelensky thought “Kissinger’s calendar” was not based in “2022, but 1938.” Echoing Zelensky, a number of U.S. and UK international relations ‘experts,’ commentators and politicians also condemned Kissinger for invoking the spirit of appeasement. Cambridge historian Robert Tombs wrote “Neville Chamberlain’s appeasement of Hitler in 1938 is the worst example in modern history of realism that did not work.” Any conciliatory diplomacy, he continued, could only strengthen aggressors “delaying conflict while making the inevitable reckoning worse.” Summating this perspective, Juliet Samuel opined that:

The strategy of NATO and its allies should be clear: deliver enough aid for long enough that Ukraine can regain its territory and mount several counter-offensives on military targets in Russia to achieve an unambiguous Russian capitulation and an abandonment…of its ambition to take Ukraine.

Samuel’s opinion piece responded not only to Kissinger style temporizing, but also to the observation from Lord David Richards, former head of the British Army, that Britain and the U.S., the powers supporting a ‘maximalist’ line against Russian aggression in order to shore up the ‘rules based international liberal order,’ lacked “a grand strategy about how we want the war to pan out.”

The debate shows that, whatever else, the seemingly united Western front against Russian aggression has begun to fray as sanctions backfire upon European consumers confronted with rising food and energy prices, whilst Russia adopts tactics in the Ukraine previously employed by the Roman Empire “to create a wilderness and call it peace,” as Tacitus had the Caledonian chieftain Calgacus phrase it. Thus Anthony Blinken, U.S. Secretary of State, and Liz Truss, the UK Foreign Secretary, view the war in Manichean terms as a global struggle between the partisans of democracy and autocracy. From this perspective, the conflict has become a proxy war between the West and Russia. Thus, the Kiel Institute for the World Economy calculates that in order to sustain Ukrainian resistance, between January 24 and May 10, 2022, the West provided at least €64.6 billion worth of military, financial, and humanitarian commitments to the Ukraine, of which €42.9 billion (66%) came from the United States. However, realists from the Pope to Victor Orban reject an eschatological view of the conflict and seek a “practical accommodation to reality not a unique moral insight,” as Henry Kissinger phrased it in World Order (2014).

The acid test of realism, Robert Tombs argued is “whether it works.” Evidently Tombs feels that any recourse to appeasement in the Ukraine cannot work, but is this always the case?

The ready invocation of the Munich Agreement, to silence any suggestion of practical accommodation to the circumstances, evokes mythology rather than accurate history. As A.J.P. Taylor demonstrated in his neglected history, The Origins of the Second World (1963), the appeasers “were men confronted with real problems doing the best in the circumstances of their time… Only those who wanted Soviet Russia to take the place of Germany are entitled to condemn” them. Taylor concluded that it was possible that war may have been averted by “greater firmness or greater conciliation… either might have succeeded if consistently followed; the mixture of the two… was most likely to fail.”

Current Western uncertainty means that Ukraine runs the imminent risk of becoming irredeemably dysfunctional whilst Russia could end up as China’s Belarus. Both possibilities are less than optimal. Why, we might wonder, is democratic diplomacy so dysfunctional and what might an informed realist policy entail?

Alexis de Tocqueville first identified the problem that majoritarian democracy has with realist diplomacy and statecraft. In Democracy in America (1835), he wrote that foreign affairs

demand scarcely any of those qualities which a democracy possesses; … It cannot combine measures with secrecy, and it will not await their consequences with patience … Democracies obey the impulse of passion rather than the suggestions of prudence and … abandon a mature design for the gratification of a momentary caprice.

In the world’s 21st century democracies, such criticism seems more acute than ever. The burdens on Western leaders have only increased since Tocqueville wrote. They include a 24-hour news cycle, unprecedented media scrutiny, and the need to maintain public support for a policy against a backdrop of intensive polling. Such pressure understandably leads to mistakes. Constant media briefing belies the deliberation and circumspection that diplomacy needs to work. Social media does not help, cheapening the language of diplomacy to 140 characters renders it nasty, brutish, short, and demagogic.

Meanwhile, theorists of international relations have failed to appreciate the changing nature of diplomatic practice. The idea that international affairs follow certain teleologically determined rules fails to appreciate the contingent texture of diplomatic history and practice. Rather than assuming, as liberal internationalism does, an inexorable global meliorism, it is perhaps time to reassess the traditional virtues of statecraft.

Generally speaking, the vice of much thinking about international politics is to take an excessively long view of the future and an excessively short one of the past. As a result, there exists a paradox at the heart of the liberal understanding of both international law and international politics. Use of both hard and soft power is considered appropriate only for humanitarian ends and must fulfil a set of predetermined axioms laid down in either the UN charter or by international courts. Yet a realist strategy, to be effective, requires a clear political aim that might deviate from a general rule. Western liberal intervention requires an abstract ideal applied universally. It has lost sight of the particular. The failure of contemporary Western statesmen in the 21st century to address this anomaly or to prioritize their political ends has thus led to strategic confusion from Afghanistan to Syria, the South China Sea, and now Ukraine. In this context, it might be useful to reappraise the utility of contemporary rationalist understandings of world politics and return instead to an earlier understanding of statecraft that avoided what Toulmin called “premature generalisations” (Return to Reason, 2001).

To mention ‘statecraft,’ ‘realism,’ and ‘virtue’ in the same breath frequently courts derision or disbelief. We have all been taught that politics is a cynical and opportunist game and that diplomacy between self-interested nations its most perverse manifestation. “An ambassador is an honest gentleman sent to lie abroad for the good of his country,” the English diplomat Sir Henry Wotton remarked on a mission to Augsburg in 1604. Yet few would deny the positive aspects of diplomacy—a willingness to compromise and seek compromise and, above all else, seek alternatives to conflict and war. In the modern era, our diplomatic habits might benefit from some readjustment to allow some older realist virtues to flourish.

Classically, realism was not an ideology but a disposition. It distrusts human nature and considers international rules conditional rather than absolute. From this perspective there are only three verities in world politics, diplomacy, treaties, and war. Abstract schemes founded on international law or universal panaceas are likely to disappoint. The rationalism and universalism inherent in all ideological projects—whether liberal, Marxist, or identity driven—is inimical to the scepticism inherent to a realist disposition.

Such a temperament was at a discount after the Cold War where optimism on the mainstream Left and Right of Western democratic thinking about transnational organizations and the benefits of borderless world trade assumed an almost visible hand shaping a liberal progressive world order. No one caught this mood better than Francis Fukuyama, whose ‘End of History’ saga has left, as we daily witness, an indelible trace on Western post-Cold War diplomatic thinking.

Only in the wake of the failure of the transformation of the globe along End of History lines do we realize that liberal international idealism has led us into an age of anger, stranded on a darkening plain, swept with the confused alarms of struggle and flight, where ignorant armies clash by night.

It is in this deracinated condition that a return to a realism commends itself—not because ‘it works,’ but because it recognizes the inevitability of conflict, the intractability of interests, and the dangers of life in a world of sovereign states. The virtues it applauds are not those of global justice or a democratic internationale, but rather those of prudence and vigilance as the basis of political action.

Of these classical political virtues, prudence has been one of the most prized in Western political thought and the most often misunderstood. Aristotle distinguished between three ‘virtues of thought’: episteme (scientific knowledge), techne (skill) and phronesis (prudence, or practical wisdom). As he explained in his Nichomachean Ethics, “prudence is concerned with particulars as well as universals, and particulars become known from experience.” Its Latin translation, prudentia, came to connote the practical skill involved in moral and political agency. For Greek and Roman political thinkers concerned with the res publica (‘the public thing’), it was the virtue most at home among statesmen engaged in ruling a politea.

Yet, just as ‘realism’ is a highly contingent notion, so prudence has always been an ambivalent virtue. This was, in part, because not only did it constitute a virtue itself, but it also discriminated between incommensurable virtues in circumstances where they conflict. Reflection on applied prudence reveals that all virtues do not constitute a single coherent system of the moral life, but instead exhibiting some virtues can be incompatible with acting on others. The courageous man of honour, for instance cannot always be prudent. Prudence is “a joker in the moral pack and its business on occasions, is to trump its fellow virtues” (Minogue, “Prudence” in Anderson (ed.) Decadence, 2005). The evolution of political virtues over the last five hundred years has left us with a necessarily ambiguous political vocabulary. Indeed, terms like ‘prudence,’ ‘realpolitik,’ or ‘justice’ and ‘international law’ are neither rational unities or fortuitous collections but hybrid ‘historic compounds’ that alter according to contingent historical circumstances (Oakshott, The Politics of Faith and the Politics of Scepticism, 1996). As such they are worth unpacking. To do this let us first take a brief trip to the National Gallery in London’s Trafalgar Square.

Entering Gallery 6, the discerning visitor’s eye might find itself drawn to one of the more enigmatic paintings of the Venetian Renaissance. It depicts a curious three-faced figure: the mature face of a man confronts the viewer, profiled on one side by a wizened old churl and on the other by a gamin youth. Beneath the three-faced figure sits a three-faced beast, a lion facing, profiled by a wolf on one side and a dog on the other. Across the top of the painting runs a maxim in Latin. Roughly translated it reads: “From the experience of the past, the present acts prudently, lest it spoil the future.”

Tiziano Vecelli’s (Titian) The Allegory of Time Governed by Prudence may be taken as a depiction of the three ages of man. But the allegory involves the notion of a wolf devouring the memory of the past, the lion offering the fortitude necessary to survive the present, while the dog bounds off into an uncertain future.

Titian—who painted the Counter Reformation for Philip II—saw allegorical representation as a vehicle for conveying political understanding. Like other Counter Reformation thinkers, dramatists, and painters (Rubens comes to mind) influenced primarily by Roman political insight, Titian and his patrons were profoundly aware of the need for what Tacitus had termed political prudence in all actions concerned with the art of leadership.

The recognition of the distinctive character of politics and the need for prudence and the foresight it offered in choosing the correct means to a political end became particularly acute as Christendom disintegrated. Ruling elites, whether Protestant or Catholic, searched for a formula to address the devastating consequences of religious enthusiasm and internal and external war. The formula they discovered was that of realist counsel, which adopted the political reason that prudence exemplified to contingent circumstances. The doctrine that evolved was that of the politique application of raison d’etat practiced by the more successful rulers of the period, whether Catholic like Philip II or Catherine de Medici, Protestant like Elizabeth I, or irenic like Henry of Navarre.

The 16th and 17th century political thinkers who bequeathed us our ambivalent language of government and defined the modern understanding of sovereignty and the nature of political obedience also have much to teach us about the relationship between the state and the strategic use of force to sustain external and internal peace. Yet this aspect of their thought is largely neglected. These early modern theorists of statecraft and diplomacy clarified the identity of the modern state and how it maintained and defended its right to exist, offering a practical counsel that modern Western democracies, in their efforts to maintain internal order or conduct wars of choice, could do well to consider.

The century from the Counter-Reformation to the Peace of Westphalia was almost as bloody as the twentieth in terms of the devastation it wreaked upon Europe. Between 1550–1648, Europe suffered divisive internal as well as external war, and witnessed the often brutal severing of traditional political and religious allegiances from Prague to Edinburgh. Between 1618–1648, the gross domestic product of the lands of the Holy Roman Empire (covering most of central Europe) declined by between 25–40%. The 30 Years War devastated and depopulated entire regions of contemporary Germany, Italy, Holland, France, and Belgium.

It was in the context of confessional division and internecine war that the modern unitary state emerged unsteadily from the disintegrating chrysalis of the medieval realm. With it arose a new scepticism about morality, law, and order that came to be termed politique, prudent, or reason of state. The realist thinkers that outlined this political project—from Niccolò Machiavelli and Jean Bodin to the neglected, but at the time, highly influential Dutch humanist Justus Lipsius—were notably wary of abstract moral injunctions when it came to difficult questions of war and peace. Instead, they offered a distinctive counsel of prudence, or practical morality, when considering the use of force.

Practical 16th century guides to statecraft offered maxims to address difficult cases like war. This practical advice to princes and republics on morality and war contrasts dramatically with contemporary international law and its application of a universal moral and legal standard to all cases concerning the use of force.

Yet a return to a prudent rhetoric of reasonableness, especially in foreign policy debates, could restore the balance that an abstract legal rationalism, and its preoccupation with certain rules and systems, has disturbed. In a world of uncertainty and complexity, abstract rationalist rigour is less appropriate than the 16th century humanism of those like Michel de Montaigne, who exhorted his readers to live with ambiguity without judgment. Indeed, as Stephen Toulmin has argued, an updated prudential and practical ethics, or casuistry, can still have value in resolving doubtful cases ranging from war to euthanasia in the 21st century.

What then was the character of this practical case analysis, and what implications does it have for statecraft and strategy? To recover this prudential view, and what it means for contemporary strategic thought, requires first that we establish how a distinctive approach to difficult cases of obligation emerged in the 16th century as a response to confessional division and political fragmentation. This evolved as humanist philosophers and statesmen promiscuously raided Aristotle’s Rhetoric and Nicomachean Ethics, Cicero’s De Officiis, and the histories of Tacitus, Polybius, and Livy, for practical case ethics and a set of maxims to address questions of war and peace. In the process of interrogating the classical world for advice on political conduct, they walked looking backwards into a modern realist or more accurately prudential understanding of statecraft.

A prudent political engagement required, as Machiavelli stressed, a keen awareness of necessity, together with a clear-eyed interest in practical reasoning rather than passion, religious enthusiasm, or popular opinion (see Mansfield, Machiavelli’s Virtue, 1996). We might finally consider then how this humanist approach to political reason might address contemporary problems in world politics.

Ultimately, the 16th century politique realism that its leading advocates like Justus Lipsius (who ironically later gave his name to the European Parliament building) pioneered a preoccupation with utilitas at the expense of honestas, with Lipsius outlining this in his Politicorum Sive Civilis Doctrinae Libri Sex (1589). In this way, these advocates addressed ethically the evolving predicament that the early modern (as well as the postmodern) politician faced, namely the problem of deliberating and presenting controversial policies in contingent circumstances of change and uncertainty.

This practical philosophic approach to difficult cases differs from either rationalist realist caution or international legal rationalism in its sensitivity to the difficulty of applying abstract norms to the lived experience of difficult cases. In the liberal international rules-based order “general ethical rules relate to specific moral cases in a theoretical manner, with universal rules serving as ‘axioms’ from which particular moral rules are deduced as theorems.” By contrast, for a prudent casuist, “the relation is frankly practical with general moral rules serving as ‘maxims’ which can be fully understood only in terms of the paradigmatic cases that define their meaning and force” (Jonsen & Toulmin, The Abuse of Casuistry, 1988). Such an approach emphasises practical statements and arguments that are “concrete, temporal and presumptive.” In the practical field of international politics, unlike the exact theoretical or natural sciences, immediate facts and particular and specific situations affect the very different practices of deliberation, presentation and judgment.

Contra its modern liberal critics, prudence, statecraft, and raison d’etat was not informed by an immoral view of political conduct but evolved what its advocates described as ‘mixed’ prudence that advisers to statesmen and princes adapted to address the predicament of internal rule and external threat. Following such counsel, we would arrive at a different and perhaps more practical set of maxims for difficult and ambiguous cases, whether it be the West’s response to Putin’s intervention in Ukraine or its failure to intervene in Syria.

In such difficult cases, a modern-day practitioner of prudent advice would contend that the counsel offered to a president would recognize the necessity of a situational ethical practice that directed the prince to that “great goal that is the common good.” This is particularly the case in global politics where opinion and passion, both transitory and unstable, influence the masses. Wise counsel must take into account popular credulity and fecklessness. This necessarily affects the conduct of the prince or president who in order to maintain stability and peace must of necessity have recourse to a mixed prudence that adjusts to a “reality that is changeable in every respect.” Such a mixture makes use of both simulation and dissimulation to advance the common good. Indeed, while truth is better than falsehood, as the ancients acknowledge “experience shows the dignity and qualities of both.” In difficult cases, prudent conduct might, in other words, “depart from human laws, but only in order to preserve his position never to extend it.” For necessity, as Machiavelli first intimated and Lipsus later rephrased, “being a great defender of the weakness of man, breaks every law.”

Hence, mixed prudence and virtue are the two leaders of civil life, but prudence, as we have seen, is as Lipsius puts it, “the rudder that guides the virtues.” In particular it ‘offers insight’ into cases of war or peace and the state’s right in such decisions. Here history and experience, rather than abstract norms, play a central role in determining a prudent course. Indeed, “history is the fount from which political and prudential choosing flows.” Since the end of the Cold War, such a mixed prudential view of international politics has been honoured only in the breach both by US and European governments as well as their idealist critics.

By contrast, wise counsel to the more successful early modern monarchs recognized the danger of presenting advice in overly idealistic terms that could lead to a damaging loss of credibility. Indeed, and in the context of NATO’s eastward expansion and Putin’s reclamation of the Crimea, ‘the pretence’ of idealism, as Lipsius recognized in the not so different Spanish Netherlands of the 1590s, often “ignites the fires of strife” across Europe. A wise prince in such circumstances would prefer the mixed prudential application of the material of deliberation to the requirements of presentation. Ultimately, a prince in troubled cases like Ukraine and the Crimea would recognize, unlike Liz Truss or Volodmyr Zelensky, that he “must do not what is beautiful to say, but what is necessary in practice” (Lipsius).

Indeed, an early modern realist would be astonished at how little prepared the political class in the West are for war. Lacking knowledge of military prudence, they are unlikely to deliberate slowly over the reasons for the use of force or the outcome of using it. Lack of attention to history (memoria) and examples (exemplum) leads to the problems encountered in Afghanistan and Iraq and a failure to appreciate Russia’s long term strategic interest in eastern Ukraine or China’s in the South China Sea.

More particularly, the West’s conduct of international relations increasingly requires an awareness of the arcana governing all interventions and the need to practice a differential political morality. This would recognize the importance of Tacitean and stoic advice on the difficulty of political action. Linking raison d’etat to active prudential virtue rather than theoretically abstract rule-guided moral consequentialism would, a contemporary realpolitician might argue, offer a limited ethical practice more easily adjusted to our “troubled condition of confusion and change.”

Whereas prudence emphasizes political or reasonable action adjusted to particular and contingent circumstances, liberal progressivism like other forms of modern rationalism sees global problems only in terms of universal panaceas. Prudential reasoning about the political and international condition that formed the basis of both early modern and much modern statecraft got lost in the Cold War era of ideological confrontation and the post-Cold War one where the end of history seemed to offer a post-ideological condition suffused by international norms.

To the extent that the dominant global power the U.S. considered prudence at all, it existed in the somewhat desiccated form of a concern with caution and restraint. Yet, as Machiavelli observed in The Prince, “All courses of action are risky, so prudence is not in avoiding danger (it’s impossible), but calculating risk and acting decisively.” Mixed prudence perhaps offers the foundations of a more realistic strategy, predicated on the foundations of existing political thought, for the troubled 21st century.