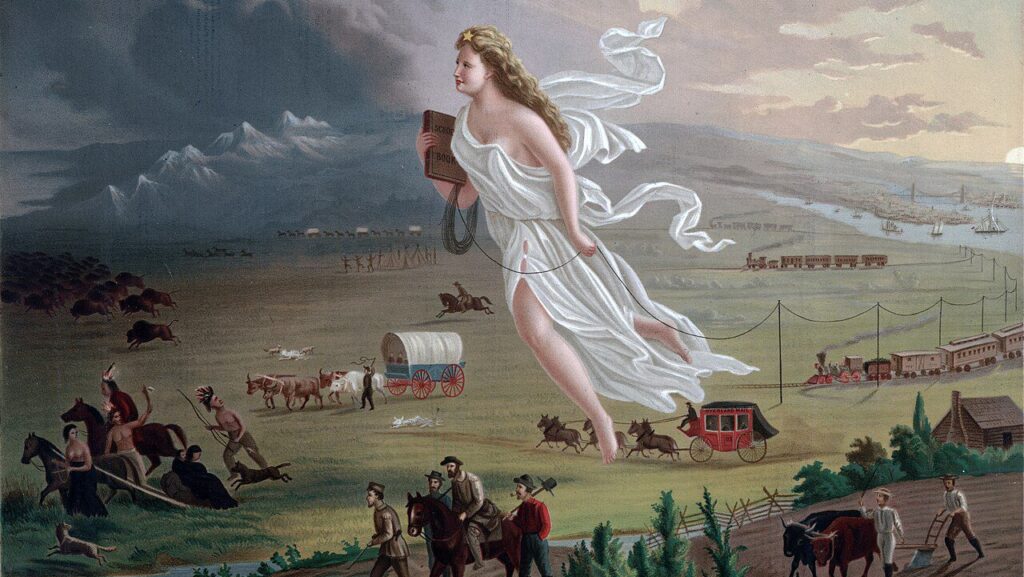

American Progress (1872), a 29.2 cm x 40 cm oil on canvas by John Gast (1842-1896), located at the Autry Museum of the American West, Los Angeles

Although it has only been a few decades deemed the world’s “hyperpower,” the history and cultural developments driving its current slide towards political and economic sclerosis are rarely discussed. Instead, America’s troubles are explained by particulars, like Donald Trump’s tweets and Joe Biden’s dementia. I am therefore grateful to have the opportunity to present a few high points from my book, Radical Betrayal: How Liberals & Neoconservatives Are Wrecking American Exceptionalism. It goes beyond the banalities of Trump haters, media bias, and academic prejudice, to explain today’s crisis through the (cracking) lens of American Exceptionalism.

Because my analysis deals with U.S. nationalism, it is best to begin by recalling that national narratives have been a political force since Antiquity. However, most of these proto-nationalisms focused on the kings who maintained them, not the common people. Thus, they didn’t develop into forces strong enough to sustain national identities through periods of conquest and weakness. As a result, states rose and fell at a breathtaking rate, and peoples like the Jews, Athenians, and Spartans continued to define themselves as members of small tribes rather than larger nations. There were some exceptions, of which the Romans are the best known. By extending citizenship, they created a sense of community and gave people in conquered areas a vested interest in the empire’s well-being.

During the Middle Ages, European rulers reverted to a king-oriented state ideology. In England, however, a proto-nationalist narrative emerged after King John signed the Magna Carta in 1215. This document created a number of “English freedoms” encouraging the development of a new type of society marked by, for example, personal rights for “to all freemen of our kingdom,” and power sharing between Parliament, the King, and courts. Later, this ethos merged with the Puritan view of North America—a “New Israel” settled by God-fearing people who were destined to create a model nation—forming the embryo of American Exceptionalism in the process.

In 1776, the colonists’ desire to protect their “English freedoms” triggered the American Revolution. Through the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution, Christian beliefs, English realism, and Enlightenment idealism combined in the world’s first full-blown—and so far, most successful—modern nationalism. However, to grasp the full scale, scope, and influence of this original form of exceptionalism, two episodes of early U.S. history must be considered.

First, Alexander Hamilton’s view—that U.S. markets needed to be protected by tariffs— outlived Thomas Jefferson’s ideal of America being an “Empire of Liberty.” As the country grew large enough to escape the snags of protectionism, that outcome preserved a small government and free market regime that rapidly made America the richest country in the world. It also cemented the American inclinations towards personal freedom, local resolution of social issues, and more.

The second event was George Washington’s decision in 1789 not to support the French Revolution in an active role. This created a non-interventionist tradition that, with some exemptions, endured until World War II. In other words, America settled on being a model, rather than a creator, of freedom in other lands. As John Quincy Adams put it in 1821, “We Americans do not go abroad in search of monsters to destroy.”

Bolstered by exceptionalist sentiments, these episodes formed a unifying worldview strong enough to hold the Union together despite growing ethnic, social, and cultural differences. Moreover, principles like limited government, states’ rights, low taxes, and a non-interventionist foreign policy, formed a super-ideology embraced by nearly everybody. Nineteenth-century U.S. politics overall accordingly became an ideologically dull affair, punctuated only by serious clashes about particulars such as the need for a federal bank, the continuation of slavery (that even led to a Civil War), and the level of tariffs.

Around 1900, this unity began to crumble. One reason for this was that, as the U.S. became affluent, so also grew the strength of the missionary impulse implicit in viewing America as a model society of freedom. In other words, as people realized that the U.S. had the means, they felt obliged to start spreading freedom and their values more vigorously. So, with the Spanish-American War in 1898, the U.S. began expanding its international role, such as by acquiring outposts in the Caribbean and the Pacific.

Simultaneously, the Democrats started moving politically leftward. The reason for that change was because, since the Civil War, the party had faced a precarious electoral position due to its support for slavery and its association with the Ku Klux Klan. Subsequently, in an effort to rebrand itself, by nominating populist firebrand William Jennings Bryan for president in 1896, 1900, and 1908, it began to depart from its traditionally libertarian program, adopting more statist-market intervention stances instead.

In 1912, these developments coalesced when Woodrow Wilson became president. Elected with only 42%t of the vote (as the Republican vote split between President William H. Taft and ex-President Theodore Roosevelt) and as a figurehead of the Progressive Movement, he held several views that were alien by American standards. For example, he regarded the U.S. Constitution as outdated, believed in human perfectibility, and thought that the U.S. Government could be used as a force for good. Thus, the Democrats’ view of America and its role began to oppose the original belief in exceptionalism.

Nonetheless, by expressing himself vaguely and by redefining traditional terms, Wilson managed to push through his policies. At home, he signed bills creating the Federal Reserve and introducing a federal income tax. And in 1917, using exceptionalist-sounding rhetoric, he dragged the U.S. into World War I with the goal of creating a New World Order. The Treaty of Versailles—based on Wilson’s personal beliefs rather than exceptionalist values—set the stage for World War II. By then, the transformation of America from a free republic into a full-blown welfare-warfare state had begun, yet radicals would continue to drape non-American policies in exceptionalist-sounding rhetoric.

For example, Franklin D. Roosevelt sold parts of the New Deal as temporary deviations aimed only at resolving the Great Depression and preserving “the American way of life.” And after John F. Kennedy mastered the art of boxing liberal policies in exceptionalist wrapping paper, Lyndon B. Johnson pushed through both a tax cut and his Great Society program, promising to fix everything: from addressing the lack of local libraries to the eradication of fear, want, poverty, and racism. And the budget deficit this created was only one effect; the federal apparatus turning into a true Leviathan, set at fixing everything from potholes to global warming, was another.

However, the Great Society made the difference between exceptionalist-sounding rhetoric and liberal policies too stark to resolve and, after 1970, many liberals began to sound more like European than American politicians. This dual rhetorical-policy departure from American tradition triggered the Cultural Wars, a series of conflicts between conservatives and progressives over issues of identity, values, and morality that has become so bitter that it today threatens the survival of the Union.

Certainly, the Right is partially to blame for America’s current problems. Even if the GOP has remained committed to low taxes, few regulations, and individual freedom, the party has—under the influence of so-called neoconservatives—deviated from its earlier principles in other areas, the most important of which are foreign policy and budget discipline. In a word, neocons have bested the Democrats’ advocacy for an aggressive foreign policy and, by uncritically adopting supply-side economics, have contributed to today’s chronic budget deficit and a national debt of $33+ trillion.

Much more could be said about these and other matters. However, these considerations alone show how badly flawed is the established narrative about modern America, its characteristics, and its policies. As just one example, for more than 50 years the cultural wars have falsely been blamed on the GOP taking a “hard right turn” under Ronald Reagan. More serious is that both parties have distanced themselves from the ethos of American Exceptionalism. This has created a gap between popular and elite discourses about what the U.S. is and what its goals should be, blurring people’s sense of community, and weakening exceptionalism’s role as a glue that holds the country together.

Furthermore, even if both sides do share blame for these developments, the Democrats nevertheless bear the principal responsibility. By adopting European tax, welfare, and other policies, they have given roughly half the population a schizophrenic view of what it means to be an American. Over time, they have effectively offered provisions for purely anti-American views and sentiments stemming from within media and academia.

After Wilson, FDR, and LBJ, the main culprit in creating this state of affairs was Barack Obama. He concluded the Democrats’ mutation into a full-scale left-wing party focused on giving entitlements to strategic voter groups and keeping the country’s borders open, rather than helping struggling people improve their situations. Also, in his bid to create a new electoral majority of youth, women, unionized workers, immigrants, LGBT, and college-educated liberals, he exacerbated the culture wars and reversed decades of progress by deliberately stirring social, racial, cultural, and other forms of mistrust.

Moreover, Obama’s failed policies led to a depressed ‘new normal’ that Donald Trump turned out to be a master at challenging. His pledge to stand up against the globalist cabal in D.C. and to “make the country great again” went hand in glove with the concerns of disgruntled Americans. And by (e.g.) focusing tax cuts on working- and middle-class people (instead of important voter blocs and special interests) and renegotiating unfavorable trade deals, he succeeded. Almost, for at the last minute, Democrats and the media managed to use the COVID-19 hysteria, along with some creative voter collection methods, to derail his reelection.

Now, the Biden administration has reversed most of Trump’s successful policies and implemented new ones that have added to the vilest part of the old order. It has increased federal spending to a new record level, which in turn has led to both a rise in inflation and the national debt; it has raised popular expectations of what the government can do in the realm of welfare by promising things like a student loan forgiveness program that would be extremely expensive and destructive to fostering a sense of personal responsibility; and it has promised infinite amounts of military and economic aid to Ukraine and Israel, which has tied up the country in two new “endless wars” in faraway countries (next to Syria and other current conflicts).

In summary, America must bridge its economic, cultural, and other divides by reinvigorating American Exceptionalism. Otherwise, the U.S. will fall, which would not only be historically poignant but also dangerous, since powers like Russia, China, and Iran would gain immensely from such a disaster. And, because the Democrats bear the principal responsibility for today’s situation, they must back away from the brink and once again embrace more exceptionalist rhetoric and policies. If they do not, the political, social, and cultural tensions in America will continue to increase until the nation rips itself apart. The only alternatives to such an outcome would be to split the Union peacefully beforehand, or for the federal level to become more autocratic. Unfortunately, given events such as U.S. intelligence agencies’ mass surveillance of U.S. citizens, the White House’s efforts to censor free speech online, the hiring of 10,000 new and armed IRS agents, and the legal maneuvers designed to jail Donald Trump ahead of the 2024 election, the latter is where things seem to be going.