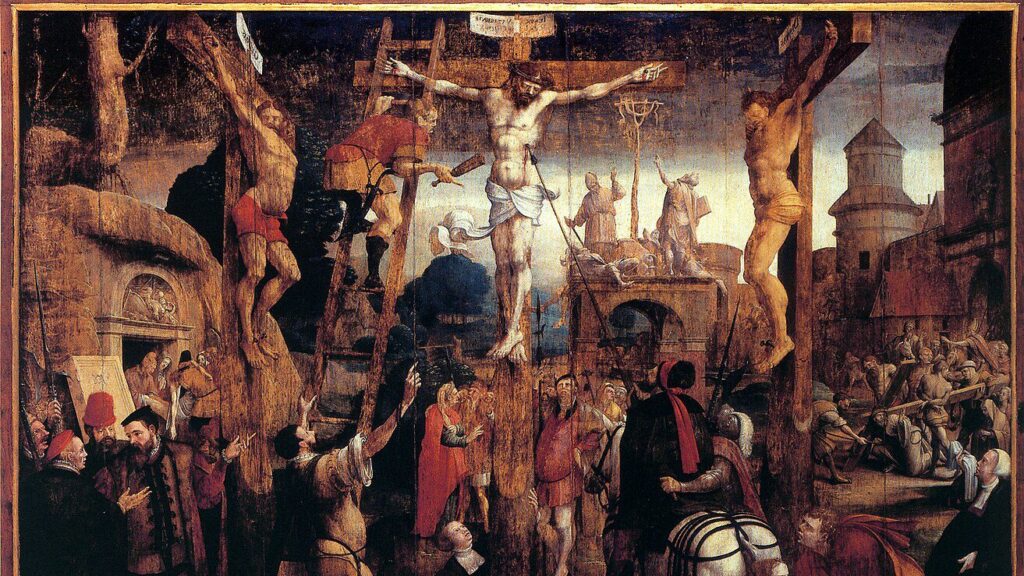

Kalvarienberg (c. 1550), a 170 cm x 211 cm oil and tempera on oak wood by Hermann tom Ring (1521-1596), located at the Westphalian State Museum of Art and Cultural History

There comes a time in every Christian’s life when he first realizes that he has never really seen the Cross. He has looked at it, through it, or past it, but never lingered there.

Mine came in the environs of what had heretofore been my refuge—floating in the Pacific, beneath the hollowed skeleton of a decommissioned nuclear power plant, just north of a massive marine base, Camp Pendleton, in San Clemente, California. I caught a wave—something I’d done thousands of times before—but this time I fell off. That was strange, I thought. But then it happened again. And again. My right arm and leg were weak. I paddled into the beach, but the malady followed me to the shore. I fell over and over again; fear slowly usurped the place of confusion in my mind. The waves knocked me down, as if I were an infant who needed to be held up by the arms. Maybe I can sleep it off, I thought. The human capacity for denial knows no limits.

Two days later, after a battery of tests, I was diagnosed with spinal stenosis, for which I would need to be operated on immediately, as well as an ‘incidental’ finding of a lesion in my brain that would also likely need to be surgically removed. At 38, I didn’t feel ‘tested’ by God; I felt robbed by fate.

“You seduced me, Lord, and I let myself be seduced,” says the Prophet Jeremiah (20:7). In another translation, the deceit is perhaps even more visceral: “You duped me, Lord, and I let myself be duped.”

That is how I felt too—duped, seduced—lying on a hospital bed as I awaited surgery, with birthday balloons tied to the arm rails of my bed. Richard Neuhaus’ words in his prose poem of Christian meditation Death on a Friday Afternoon also seemed, even after I made it home safely from the first operation on my spine, like a taunt:

Stay a while. Do not hurry by the cross on your way to Easter joy, for we know the risen Lord only through Christ and him crucified.

As naive as it sounds now, I somehow always thought I would get to set the terms of my ‘staying a while.’ I wasn’t overweight; I exercised regularly. My cross would come to me later, if not at an hour of my choosing.

When the priest came to anoint me before my surgery, he did his best to put my suffering into context. “You have every right to be upset,” the priest told me in his melodic foreign accent, tinged by a tongue from an African country whose name I will never know.

“It’s unnatural,” he continued, “for you to be here in the hospital when your little girls are at home and your wife needs you.”

Death, I thought to myself, is unnatural. And it’s unnatural that I should see my daughter’s first day of school in a text message picture, not from my front lawn.

“Let me tell you, though,” he began, “about a 93-year-old woman I was just visiting. She was surrounded by her children. Just a few weeks ago, she was cooking for them. They miss her food. They want her to come home, and she wants to be at home too, cooking for them.”

And hence one of the ways I’d looked past the Cross and not into it: When I saw the elderly dying, or near death—my grandparents, for example—I assumed it was somehow easier for them to accept because ‘their time’ had come.

After I got home from the hospital, I ordered a copy of the Catechism of the Catholic Church. If I were going to contemplate the Cross, I figured I should do it from every possible angle, so I looked up the word ‘suffering’ in the index.

The longest passage on suffering, according to the index, dealt with the sacrament of anointing of the sick. To say that the catechism’s explanation of the sacrament and of the role that suffering plays in it is paradoxical would be an understatement. According to the Catechism, those who receive the sacrament are bestowed with:

The gift of uniting himself more closely to Christ’s passion. … He is consecrated to bear fruit by configuration to the Savior’s redemptive passion. Suffering … acquires a new meaning; it becomes a participation in the saving work of Jesus.

The words seemed preposterous. How does our suffering save us? How did—how does—Christ’s suffering save? Does suffering have any meaning at all? In that same moment, almost unconsciously but also intuitively, I understood that all objections to Christianity—from scientific to sexual—are fundamentally objections to the Cross. All of us harbor a Nietzsche within, rebelling not against God per se but against Christianity’s worship of weakness.

Now that I am back at work, in a brief interlude between surgeries, I drive by a cemetery every day. A neighbor who also suffered from a brain tumor is buried there. After his name, the inscription on the tombstone reads: “A man who suffered for God’s glory.”

The inscription was composed by his young daughter. According to his wife, his faith, even unto death, had the opposite effect of what he had most feared: his sufferings drew his daughter closer to God, not further away. His daughter understood Christian suffering better than I did. Through Christ, weakness becomes strength; through her father, who bore his cross with quiet courage and dignity, his death—however prosaic by the laws of nature—became for her a powerful form of Christian witness.

“My grace is sufficient for you,” Christ tells Paul in 2 Corinthians, “for power is made perfect in weakness.” If a child can understand the Cross, then surely I can too.