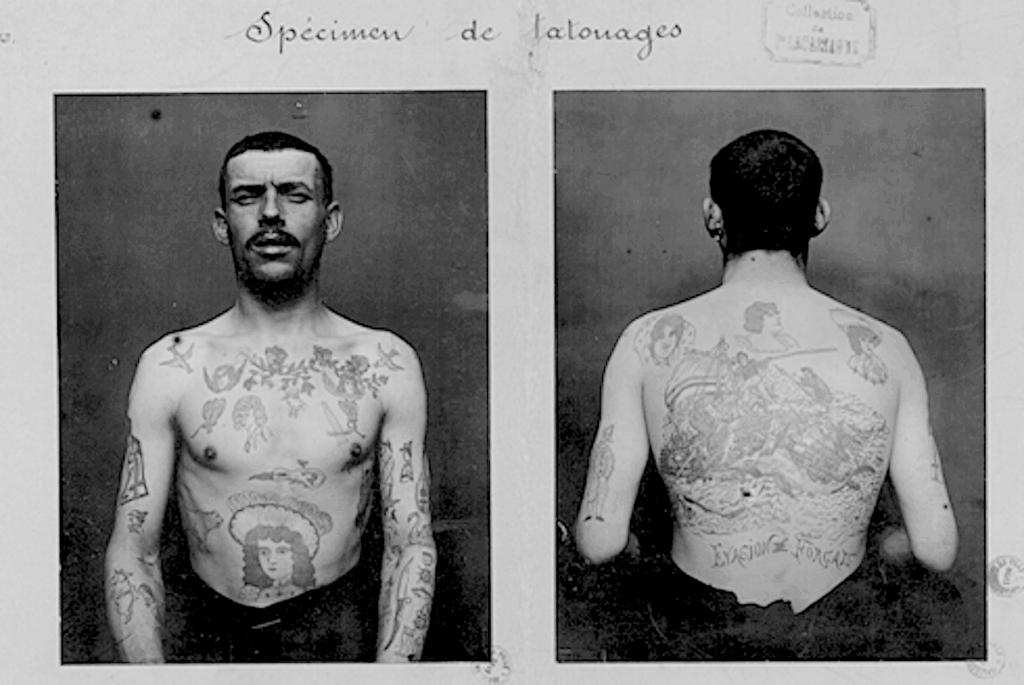

Undated photo of a tattooed French soldier from the Alexandre Lacassagne collection, Bibliothèque municipale de Lyon.

On Sundays in the early 1960s, I often used to spend the afternoon on my own at Speakers’ Corner in London’s Hyde Park. No one in those days thought it odd, or a sign of parental neglect, that a child of my age should wander on his own in the centre of that vast city. Such freedom was not granted or protected by law: it was part of the culture, the mores, of the time. It never entered my head that things would ever change, that such freedom for twelve- or thirteen-year-olds would come to an end, for it is part of the human condition to think that the present moment is eternal and unchanging.

Speakers’ Corner was a small area of the park where socialists, vegetarians, Christians of all denominations, humanists, anti-vivisectionists, and orators of every description would stand on a soap box and declaim, competing for an audience. It was all entirely without supervision, with no one to protect anyone from having their feelings hurt, or to deny anyone the right to say whatever he wanted, though in general everything was conducted with decency, in good, humour and without rancour. The friar from the Catholic Truth Society regularly took up a position opposite the member of the British Humanist Society and they exchanged little jibes without personal animosity. I can still see the friar in my mind’s eye, a short and rotund little man with thick round spectacles, laughing at his own jokes. I did not know it then, but they were days of innocence.

There was one man—I suppose he was in his fifties—who was different from all the other soap box orators, for he was completely silent. He never uttered a word, but stood, an enigmatic smile on his face, slowly removing his shirt to reveal a torso entirely covered in tattoos. His body was his message, the only thing he had to communicate. His audience was quite large, though shifting, for people have always been interested in freaks and freakishness. Most people tittered slightly nervously, perhaps because they considered it impolite to mock, or perhaps because evidence of human folly is always slightly anxiety-provoking.

There is no new thing new under the sun—or, at least, no entirely new thing. For example, Captain George Costentenus used to exhibit himself all over Europe and North America in the 1870s and ’80s, including at the Folies-Bergère, having been (he claimed) forcibly tattooed from head to toe by Tartars and Burmese during his adventurous life around the world.

In 1881, the great French forensic pathologist, Alexandre Lacassagne, published a short book on tattoos and tattooing. He was, perhaps, one of the first investigators to consider the psychological meaning of the phenomenon among Europeans. He had become interested in the subject when he was doctor to battalions of the French army in Algeria composed of men recaptured after desertion or guilty of other military offences, and he remained interested in the subject for the rest of his life.

Lacassagne (1843–1924) was a most remarkable man. No one contributed more than he did to the foundations of forensic science, but he was as interested in the psyche of criminals as in the way blood splashed from knife wounds or the rate at which bodies decayed. He was a highly cultivated man, apparently able to recite much of Dante by heart, and was a bibliophile who left his precious collection of 12,000 volumes to the city of Lyon, in whose university he was professor for thirty-three years.

He devised a method of transferring the design of tattoos to paper and collected 2,000 examples. In those days, of course, tattooing was technically much less sophisticated than it is now, and was largely confined to soldiers, sailors, criminals, and other marginalised people, with a few monarchs and aristocrats thrown in (who had themselves tattooed under very special circumstances).

Lacassagne rejected the theory of the other great criminologist of the time, Cesare Lombroso of Turin, who devoted a chapter of his most famous book, L’Huomo delincuente (Criminal Man) to the phenomenon. According to Lomboso, the special attraction of tattoos to criminals was an atavism, a throwback to a more primitive state of human existence, of which the supposed physical characteristics of criminals—a prognathous jaw, for example, or a sloping forehead—were also evidence.

Lacassagne disagreed. Tattooing was not a throwback, because it had never disappeared from the human repertoire. In preliterate societies, to be tattooed was the privilege of the higher classes. Tattooing expressed symbols and symbolic thought when there was no other means of expressing them. As societies became more literate and artistically advanced, tattooing moved from the highest to the lowest class, whose members were the least able to express their thoughts or feelings in any other way.

Many of the tattoos he described in his short book were very simple, indicative of a state of hatred, cynicism, or despair: ‘Death to French officers,’ ‘Long live France and fried potatoes!,’ and ‘The past deceived me, the present torments me, the future terrifies me.’ Below the umbilicus, tattoos were erotic, and even penises were often tattooed. The sheer coarseness of a life in which such massages and symbols were worth inscribing forever on the body, at the cost of pain and even danger (infected tattoos sometimes led to amputation or even death), can be imagined.

When I started to work in British prisons in 1990, I discovered that virtually all white British prisoners were tattooed, but mostly in a crude fashion that Lacassagne would have recognised. The most sophisticated tattoo, technically, was a spider’s web tattooed over a shaven skull and face. My powers of empathy failed entirely before this phenomenon: I could not begin to imagine what it was like to desire such a permanent disfigurement, or to think that it was an adornment.

Most of the tattoos were simpler, though: dotted lines around the neck or wrist with the words Cut here inscribed above or below them; Made in England tattooed round a nipple; a crude picture of a policeman hanging from a lamppost on the inside of a forearm; or simply the letters ACAB tattooed on the knuckles or the back of the fingers. This acronym stands for All Coppers Are Bastards, though down at the police station it would be claimed that it stood for Always Carry A Bible. Interestingly, this acronym now appears painted on walls in France—a tribute, I suppose, to the spread of colloquial English. Sometimes, 1213 (the numbers of the letters of the alphabet) is substituted for ACAB. It is a kind of semi-secret message, a sign to anarchists and other opponents of everything that exists that they are not alone.

Lacassagne would not have been surprised by this: he thought there was a strong psychological and cultural link between tattoos and graffiti. But he would, I think, have been astonished at, and puzzled by, the explosion of elaborate and professional tattoos in the general population in the last three decades (by 2018, 29% of French adults under the age of 35 were tattooed; and probably, by now, the percentage is even higher), such that the kind of people for whom a tattoo would have been unthinkable only thirty years ago now sport entirely tattooed limbs.

When I say that Lacassagne would have been puzzled by this, I mean this as praise, not as faint denigration: for it is surely remarkable that so visually startling a phenomenon as that which can be seen on every street in the western world should have gone so comparatively unremarked and unquestioned, much less decried. Lacassagne was the kind of man who noticed precisely what went unremarked by others, trifles that turned out not to be trifles. He was like Sherlock Holmes (whom he read), who said to Dr. Watson, “You see, but you do not observe.” For those who do not observe also do not seek for explanation of that which requires explanation.

What would Lacassagne have made of the sudden vogue for tattooing in the Western world and its normalisation in the statistical sense? Although he was a physical scientist who cut up bodies and performed tests on tissues, he would, as a man steeped in literature, have sought its cultural and psychological meaning. Clearly, those who get themselves tattooed are expressing something—but what, exactly? I do not think it altogether reassuring about the mass psychology of the west.

Let us take a simple example (as Lacassagne would have done): the tattooed butterfly. As butterflies become rarer and rarer in the real world, so the tattooed kind become ever more common on the shoulders, buttocks, and ankles of young (and not so young) women. But what do such butterflies signify? Here we may turn to Charles Dickens for illumination, and to the character of Harold Skimpole in Bleak House. Skimpole, a shallow, charming, calculating faux naïf says:

I only ask to be free. The butterflies are free. Mankind will surely not deny to Harold Skimpole what it concedes to the butterflies.

The tattooed butterfly speaks of freedom and self-pity, for it is more likely that the tattoo symbolises an aspiration than an achievement or an actualised state of being. It is precisely because a woman feels that she is not free that she tattoos herself thus, in the primitive hope that the symbolised quality will become reality in her life. We are never far from magical thinking.

But in what sense is she not free? From what does she want to be free, or what does she want to be free to do? I think the most probable answer is that she wants to be free to do whatever she pleases, when she pleases, without restraint, and to be free from the existential limitations of human life. Her little tattoo is a protest against the conditions of life itself.

Lacassagne would have been startled by, but deeply interested in, a quarterly magazine that I recently bought in France, called Tatouage, which is glossy, expensively produced,and expensively priced. It calls itself the reference publication of ‘tattoo culture.’ What lessons would Lacassagne have drawn about our society from the levels of proud self-abuse and aggressive kitschiness therein displayed? What would he have made of the advertisement on the back cover for a ‘limited edition,’ called Tattoo, of a brand of beer, its can with a tattoo design, and its obligatory warning: The abuse of alcohol is dangerous for health. Consume with moderation?