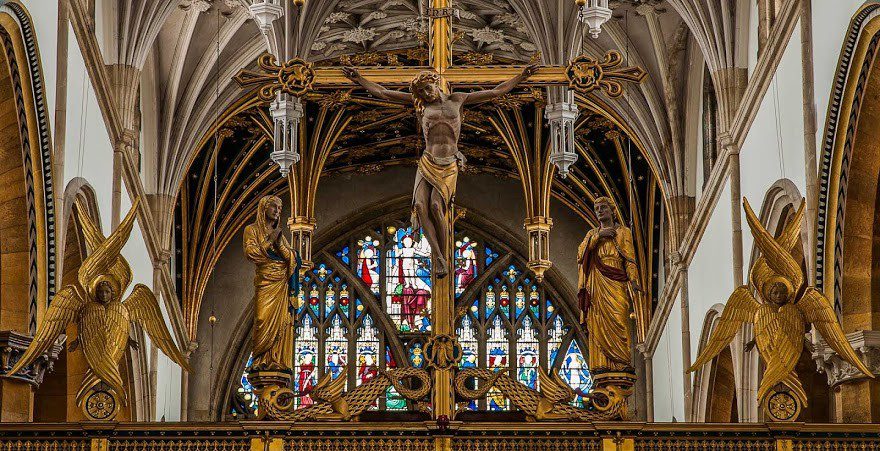

PHOTO: FRIENDS OF THE ORDINARIATE OF OUR LADY OF WALSINGHAM

In 2011, Pope Benedict XVI established ‘Personal Ordinariates’ for Anglicans who wished to conserve all they had received, spiritually and liturgically, from the Church of England but also enjoy full communion with Rome. These communities did not primarily appeal to the ‘low church’ or ‘evangelical wing’ of the Anglican Communion. As has been shown by the recent arrival of Michael Nazir-Ali, former Anglican Bishop of Rochester and now a Catholic priest of the Ordinariate of Our Lady of Walsingham, however, these communities can welcome self-identified ‘evangelicals’ too. The Personal Ordinariates responded to a movement that has haunted Anglicanism since its conception five centuries ago, namely the movement to conserve the religious character of the nation and her institutions, an aspect of which was reforming Church establishment and strengthening the nation’s ties with the Church Universal. This movement was once simply known as ‘Toryism.’

Any country that has had to slam the brakes on the noxious legacies of 1789 and 1848 will have its own distinctive conservative tradition. England, whose revolution in 1688 left such a bad taste in the mouth (gin, perhaps) that it never directly experienced the ruptures of Continental revolutions, had its conservative tradition in Toryism. Toryism (an Anglicisation of the Irish word for ‘bandit’ or ‘brigand,’ used by Cromwell’s Roundheads for Royalists found hiding out in Ireland when those Puritan toerags arrived to slaughter the Irish people) existed to defend the organic societies of the Three Kingdoms, the inherited institutions of state, and, above all, Church establishment. One cannot do better than the definition of ‘Tory’ offered in Dr. Johnson’s Dictionary: “One who adheres to the antient [sic] constitution of the state, and the apostolic hierarchy of the Church of England, opposed to a Whig.” Thus, Toryism was always profoundly opposed to Whiggery, radicalism, and liberalism.

After centuries of tacit revolution throughout this Sceptred Isle, Toryism has been well and truly ousted from both the institutions of state and polite society. Its seat of political influence, the Conservative Party, is now a force for hard-left agendas, with even its most ‘Toryish’ members claiming to be ‘liberals’ (as Jacob Rees-Mogg did during a conversation at Queen Mary University in 2018).

In modernity—which privileges technical formulae, slogans, manifestos, all to which truth is reduced in an age of general rationalism and intellectual narrowing—Toryism is at a severe disadvantage. The reason for this is that Toryism is, at bottom, attitudinal, rather than ideological. If you ask a true Tory what his political and social cause is all about, he will not give you a one-line summary. An English Tory will describe England as it is, not offer an idea of how it should be. He will talk about the Chiltern Hills, thatched cottages, drystone walls, bitter ale, the common law and its courts, Parliament, the Queen, pork scratchings, hunting with hounds, Vaughan Williams, Cranmer’s liturgical prose, and what makes for a good pair of wellington boots. In short, he will not present an abstract formula that conveys what he wants, but concrete realities which he already enjoys—and loves.

Toryism is an enduring attitude that transcends the various movements in history that have advanced its cause to conserve what is loveable. It emerged with the Jacobites and their refusal to accept the settlement of the ‘Glorious Revolution,’ by which Merrie Englande was trampled and replaced with the dog-eat-dog meritocracy and materialism of the Whigs. It continued with the witness of the non-juror bishops, and thereafter with the ‘Old Whigs’ who—inspired by the genius of Edmund Burke—defended ‘throne and altar,’ rejecting the schoolgirl enthusiasm for revolution that was rife among Charles Fox’s followers.

In the following century, Toryism grew in confidence with increasing awareness that, at the Reformation and then later with 1688, something wonderful had been lost. This intuition found expression in the Victorian appetite for medieval romanticism, which had been well-fostered in the previous century by Sir Walter Scott (whom John Henry Newman credited as a great Catholicizing force in these Isles during the 18th century). Out of this romanticism came forth the Young Englanders—who eventually gave us Benjamin Disraeli. They promulgated a social Toryism based on faithfulness to England’s ancient institutions, above all the monarchy and the established Church. They claimed that national fraternity centred on noblesse oblige could hinder the rapaciousness of the industrial elites who were exclusively loyal to the Liberals who’d become their political protectors and whose forebears had passed corrupt laws such as the Enclosure Acts, further dividing the nation’s classes with their cruelty.

There is a reason why, originally, Toryism looked back to the Stuart era for inspiration, and why romantic attachments to medieval England fed the movement for so long, even in a strange form into the 20th century. Toryism has always been haunted by the spectre of Roman Catholicism. At Toryism’s heart is the notion that all that is loveable in the nation has been animated by the nation’s transformation by Church establishment—that is, by the political and social operation of grace. For this reason, Tories have always upheld Church establishment, but so too have intuited something disordered about England’s model of Church establishment, namely the subordination of the Church to the state. Indeed, the Lord does not say, “make national churches disciples of governments” but “make disciples of all nations.”

Toryism found its voice again in a movement largely formed by Victorian medievalism: the Oxford Movement. The key question was this: was the Church meant to be a slave of the nation, or the nation—by the moral power of the Church over it—a disciple of Christ? The decision of Parliament in 1833 to reconfigure the dioceses of Ireland was, for the Reverend John Keble, a clear pronouncement that the Church was now the slave of the nation and its government. On the 14th of July of that year, the usually mild-mannered Keble took to the University Pulpit in Oxford and denounced the government for its actions and declared that the nation, as a corporate person, was now an apostate. According to Newman, Keble’s homily, known as the National Apostacy sermon, marks the date of the Oxford Movement’s founding. The Church of England had always harboured those who longed to see it reassert its apostolic descent and moral power over the nation. The Oxford Movement, which erupted into the Anglo-Catholic wing of the Church, utterly changing the institution throughout, quickly became the new home of such people.

England’s first poet laureate, John Dryden, long ago had anticipated this movement with his 1687 poem, The Hind and the Panther, written in celebration of his conversion to Catholicism. Dryden, in metaphor, called for an alliance of Anglicans and Roman Catholics—whom he clearly imagined would one day be coreligionists—against the Puritans and Dissenters in whom he saw the nation’s doom. Why was it that Dryden was so disturbed by the persistent presence of Dissenters? Because such people wanted Church disestablishment, and that would mean the nation, as a corporate person, ceasing to be a part of Christendom. In other words, for Dryden, the conflict between Anglicans and Catholics on the one side, and Puritans and Dissenters on the other, was between those who believed the Church to be visible and possessing a mission to all nations, and those who thought the Church invisible and present only in the hidden cloister of the believer’s heart.

Newman, in his Biglietto Speech, delivered on becoming a Cardinal of the Catholic Church in 1879, echoed Dryden’s concerns:

It must be recollected that the religious sects, which sprang up in England three centuries ago, and which are so powerful now, have ever been fiercely opposed to the union of Church and State, and would advocate the un-Christianising of the monarchy and all that belongs to it, under the notion that such a catastrophe would make Christianity much more pure and much more powerful.

Here, Newman states that the great danger to England are the Puritans and Dissenters—sects—who seek to disestablish the Church, and thereby secularise the nation. It is from such sects, he later tells us in the same speech, that the corrupting doctrine of liberalism was born.

As Newman shows, and contrary to popular belief, there is nothing inconsistent about being a Roman Catholic and an establishmentarian. Newman, here, is simply advancing the Tory principle. In order for England to be the organic polity that all true Englishmen love, it must be alive, as all organisms are—that is, it must have a soul, and that soul is the Church. Those who call for the divorcing of Church and State are, then, calling for the nation’s death.

Newman is not here advancing a ‘political programme,’ but, like any true Tory, is seeking to be faithful to the tradition that he has received, conserving and reforming it in the only way by which he believes it will survive. As he puts it in his Letter to the Duke of Norfolk: “We were faithful to the tradition of fifteen hundred years. All this was called Toryism, and men gloried in the name; now it is called Popery and reviled.” Newman is defending an attitude, an attitude that arose out of the discipling of England.

Newman, however, recognised that England had indeed been, albeit slowly, secularised, and that one cause of this secularisation was the degeneration of Toryism into decadence and complacency:

Toryism… came to pieces and went the way of all flesh. This was in the nature of things. Not a hundred Popes could have hindered it, unless Providence interposed by an effusion of divine grace on the hearts of men.

Toryism, at least inasmuch as it was represented in the Conservative Party, degenerated into pure Whiggery. Newman saw any revival of Toryism to be impossible without “an effusion of divine grace on the hearts of men,” without which the nation was staggering in the dark, the resultant rot of which is now on full display. Newman saw in his day that Toryism, based on the absolute principle that political life is animated by spiritual renewal through Church establishment in the constitution, had been eclipsed.

Nonetheless, Newman insisted that Toryism could never wholly disappear, for conservatism is natural to man, and conservatism must be particularised in nations as man is so particularised, and thus Toryism is natural to the English. Toryism, that great cause to keep the nation alive through Church establishment, and in turn anchor the nation in Christendom, will recurrently appear as long as England lives. “All I know,” declared Newman, “is that Toryism… springs immortal in the human breast; that religion is a spiritual loyalty; and that Catholicity is the only divine form of religion.”

Fitting it was, then, that Newman was made the heavenly patron of the Personal Ordinariate of Our Lady of Walsingham. These Anglicans were not opting for one religious ideology over another but, under the guidance of the Pontiff, seeking to prudentially reconcile this island’s post-Reformation history with the Church Universal in a way that would fully embrace Catholic orthodoxy. The theologian Aidan Nichols has put it thusly:

One of those elements which crops up time and again in Albion is… the tendency of the Church of England, despite its Reformation origins, somehow never quite to be able to put behind it its Catholic past. Hence the sporadic, not continuous, and never definitive yet always unmistakable, resurgence of something of a Catholic ethos in the Church by law established, an ethos expressed in worship, in literature, in theology. Why did I hope to see a future alliance of Anglo-Catholics with Roman Catholics in the work of converting England? It was because, even if English Catholicism were far more homogenously English in ethnic and, more importantly, cultural make-up than it is, the one thing it cannot do is represent its own missing centuries: the centuries from the accession of Elizabeth I onwards when it was marginalised, either by being persecuted or by being despised.

The cause of one day reconciling the Church Universal with the centuries during which it was missing from these isles is one that continuously pursues this nation. One witnesses it in the polyphony of William Byrd, the poems of Richard Crashaw, the speeches of Edmund Burke, the tracts of Coleridge, the paintings of the Pre-Raphaelites, the architecture of Pugin, the symphonies of Elgar, the novels of Chesterton, the essays of Eliot, the apologetics of Lewis, and the Legendarium of Tolkien.

The Ordinariate of Our Lady of Walsingham, though small in membership, is a sign of hope. The Ordinariate has re-introduced the cause of Toryism as a bridge from the nation’s pre-Reformation past to its post-Reformation era. As such, it is a bridge from the Church Universal to the Church by law established, testifying to the possibility of future reconciliation. Rather than getting rid of Cranmer’s liturgical prose, which have so transformed our language and shaped our culture, the Ordinariate has catholicised them. The Ordinariate is a fine example of realising Newman’s foundational conservative principle, namely that “of uniting what is free in the new structure of society with what is authoritative in the old, without any base compromise with ‘Progress’ and ‘Liberalism.’”