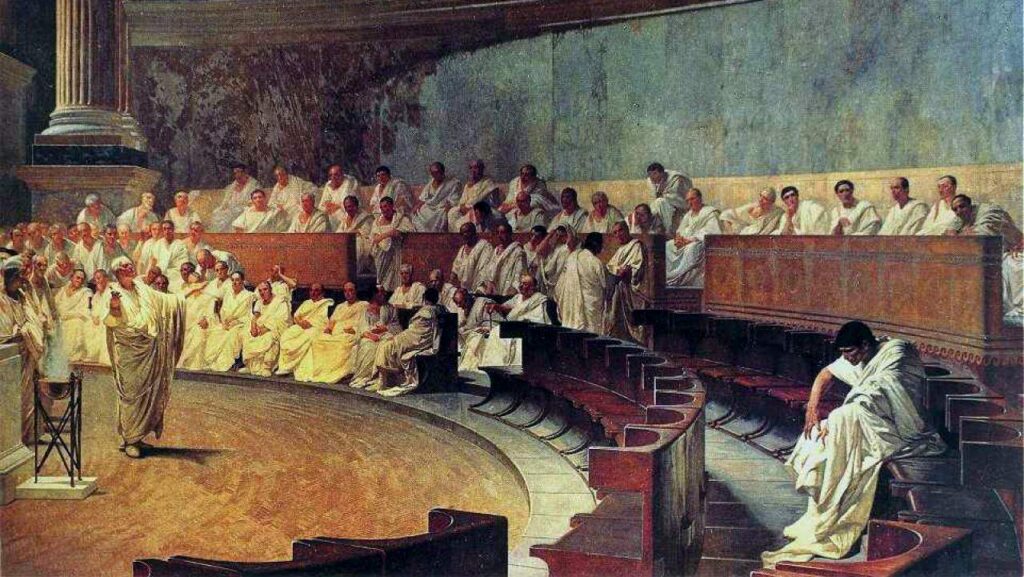

Cicero Denounces Catiline (1889), a fresco by Cesare Maccari (1840-1919)

The work of Dalmacio Negro Pavón reveals that politics cannot be understood without anthropology: the various conceptions of humanity throughout history are not mere theories but paradigms that have shaped the lives of peoples and conditioned political thought.

Discussions of ancient Roman history have been a touchstone of political commentary for centuries. Figures as diverse as Niccolo Machiavelli, Napoleon Bonaparte, and Boris Johnson have all looked to this city’s great past for lessons.

Though the Roman Empire established in 27 BC is still often mentioned today, even being the object of a viral TikTok trend in which women ask their male partners how many times a day they think about it, the period that preceded it is unjustly forgotten. The Roman Republic, traditionally understood to have existed from 509 BC to the rise of the Empire, is nowadays even more relatable. While the empire, however benevolent, was a fundamentally autocratic regime, the Republic had many constituting elements also present in our Western democracies: popular sovereignty, rule of law, democratically elected magistrates, among others. Let us then take a moment to understand the Roman Republic on its own terms, considering the figures who took part in its downfall and the circumstances in which they found themselves.

By the mid-3rd century BC, the government of the Roman Republic remained firmly in the hands of a few ruling families collectively known as the nobiles, which means ‘famed,’ ‘notable,’ and, ultimately, ‘noble.’ They were descendants of men who had been elected consuls, the highest republican magistrates. Under normal circumstances, there were only two consuls at any time, so it was an extremely prestigious position. Once a man had reached the consulship, his children and grandchildren were expected to follow in his footsteps.

Office-holding fathers would raise their sons to hold office too, and so the know-how to keep the Republic going ran within their select families for generations. Ordinary Romans were ready to cast their votes for noble candidates, although their preference for renowned names was also a heuristic technique—voting for the son, grandson or great-grandson of an illustrious former consul was far easier than keeping track of a candidate’s individual record. It is not mere coincidence that prominent Roman men often shared names with their forebears (e.g. Gaius Iulius Caesar was the son of a Gaius Iulius Caesar, the grandson of a Gaius Iulius Caesar, and the great-grandson of a Gaius Iulius Caesar).

That said, new men could still be elected based on outstanding individual qualities or achievements. Once one of these new men attained the consulship, his family became ennobled, and his descendants could look forward to a chance at power. No son of a consul wanted to fall short of his father’s achievement. A deeply timocratic and philotimic (‘honour-loving’) upbringing ensured that all young nobiles felt naturally entitled to the same honours that their elders had previously held.

Fierce competition in the pursuit of honours was a crucial aspect of Roman Republican politics, but it was not unbounded. A consul was expected to step down after a single year. A man who refused to take on a more passive role immediately after stepping down was frowned upon and looked on with suspicion. When Pompey and Crassus, who had served as consuls in 70 BC, ran for the same office in 56 BC, nobiles were not pleased—were there no other men among them worthy of the consulship? As Shakespeare so masterfully captured in Julius Caesar:

I was born free as Caesar; so were you;

We both have fed as well, and we can both

Endure the winter’s cold as well as he.

As peers, Roman nobiles were expected to strive in order to reach the top, but once they had reached it, they ought not block the path for others. For as long as this entente cordiale lasted, it gave Rome her most prosperous age, roughly a century between the end of the Second Punic War (201 BC) and the disastrous battle of Arausio (105 BC). This period of archetypal republican rule was tarnished only by two sad episodes of internecine violence—in 133 and 121 BC—that signaled the beginning of the end.

Tiberius Gracchus was a Roman nobilis, the son and grandson of two homonymous consuls, and, on his mother’s side, the grandson of the renowned Scipio Africanus. He was expected to win the consulship easily when he reached the required age to run for it. In the meanwhile, however, Tiberius decided to serve as tribune of the plebs, a centuries-old office devised to counter and check the power of the Roman magistrates.

The tribunes of the plebs had the right of vetoing the action of any magistrate and of blocking the decrees of the Senate; they also had important law-making duties. During Gracchus’ time, however, the tribuneship had simply become a stepping stone in a politician’s career—most tribunes would serve their year in office and then go on the cursus honorum (“path of honours”) that led to the much sought-after consulship.

Gracchus understood how the tribune’s secular prerogatives—although fallen in dormancy—could come to dominate the whole Roman State, and so exerted himself in reviving the lost authority of the tribune. When he wanted to run for an unexpected second term, the Senate panicked. Gracchus was popular enough to get re-elected many times, and a man perpetually serving as tribune would simply short circuit the entire republican system; Rome would become a literal monarchy for the first time in almost 400 years.

The ruling elite would not take it. Under their timocratic worldview, one-man rule was an abhorrent and totally unacceptable system of government. All these men, we must remember, felt equally entitled to enjoy the foremost position within the State—if only for a fleeting year. None had more right to it than others.

Their solution to the constitutional crisis of 133 BC was straightforwardly—and extra-judicially—to kill Gracchus as a man guilty of aiming at kingship. After that, they could breathe easy for ten years, until Tiberius’s younger brother, Gaius, decided to follow in his footsteps. Gaius Gracchus served as tribune of the plebs in 123 BC, and he actually managed to be re-elected for a second term, but in 121 BC he met a similar violent end when one of his supporters recklessly murdered a civil servant. In retaliation, the Senate had Gaius and his supporters killed.

After the demise of the Gracchi brothers, the nobiles resumed their entente cordiale, which went on for a further 17 years. In 105 BC, a Roman army of 120,000 men was massacred at the banks of the Rhone by a horde of Germanic tribes in southward migration. The Romans were terrified; they looked for a new leadership and chose Gaius Marius, consul in 107 BC, for a second term, much to the Senate’s chagrin.

Marius was as new as a man could be, but he had an impressive military record. As the war went on, the people again elected him to a third consulship, then a fourth, then a fifth, and—after the news of the Germans’ defeat reached the city in 101 BC—to a sixth. Never before a new man had served so many times as consul, and the nobiles were incensed.

When Marius finally stepped down on December 31, 100 BC, he did so reluctantly, because his popularity had finally begun to wane (the threat posed by the barbarians, after all, had been averted). He had dominated the Roman State for seven years, and he couldn’t accept the fact that he now was fated to become another former consul among many.

For the next decade, Marius sought the chance to make a comeback. In 88 BC, a Hellenistic king named Mithridates had invaded the Roman province of Asia. The Senate selected consul Lucius Cornelius Sulla to fight him, yet Marius, who coveted the assignment, orchestrated a coup. His henchmen killed Sulla’s son-in-law and drove the consul out of the city.

Sulla’s answer was to gather his army and march on Rome. Marius went to exile, but not even then did he throw in the towel. He waited. A year later Sulla had gone to the East to fight Mithridates, and the new consuls—Lucius Cornelius Cinna and Gnaeus Octavius—were quarrelling. Marius returned with a private army and offered his support to Cinna, who then defeated Octavius.

Marius ordered his retainers to enter the city and put to death every nobilis against whom he held a grudge. Afterwards, he got himself elected consul for the seventh time; entered into office on January 1, 86 BC; and died a few days later at age 70. Gripped by fever, he began to hallucinate, believing himself to be presently commanding legions against Mithridates, so that not even in his deathbed did Marius’ ambition give him respite.

His inability to be content with his unprecedented string of honours, and his stubborn refusal to follow the norms of Roman nobiles and step down, gave way to the first full-fledged civil war in Roman history. In 83 BC, Sulla returned to Italy and waged war against the Marians. On November 1, 82 BC, Sulla won a decisive battle before the very walls of Rome and had himself declared dictator.

Sulla’s dictatorship, although unprecedentedly bloody, didn’t last long. He abdicated in late 81 or early 80 BC. Afterwards, he moved to the Campanian countryside near Naples, where he passed away two years later, at age 60. Contrary to Marius, he made stepping down look easy. However ruthless, Sulla professed to be a republican at heart, and he chose to give the reins of the State back to the nobiles.

In spite of his age—barely 23 at the start of the civil war—Sulla had empowered Gnaeus Pompeius (Pompey) to act as his enforcer, and the Senate continued to have recourse to him in order to swipe up pockets of armed resistance in Gaul and Spain. He was irregularly empowered to act pro consule—“in the place of a consul”—without having ever filled that office, or any other of the previously required magistracies.

Backed by the populace, who marveled at his triumphs, Pompey successfully wrestled from the Senate the privilege to run for the consulship at 35 years old, even though the minimum age required to serve as consul was 42. As the people adored him, he easily won; the fabulously rich Crassus came in second.

For the next ten years, Pompey was a nightmare to the nobiles, who seriously feared they would wither away under the shadow of his ever-growing prestige. They exerted themselves to counter him, and Pompey answered by looking out for allies. He found one in Julius Caesar, a nephew of Marius’, who wanted to be consul. Caesar already had good relations with Crassus, and he worked to bring about a compact with Pompey. Caesar bowed to advance their interests if they supported his candidacy to the consulship of 59 BC, which they did. Caesar was elected, and it was soon too obvious that the collusion of these three men could thwart the whole status quo.

In exchange for his services, Caesar had requested a modest reward—the governorship of Gaul. Crassus and Pompey acquiesced. Little did the latter know that a war against the Gauls would provide Caesar with a glory that would outshine his own. When Crassus died in 53 BC, Caesar was no longer a junior partner of Pompey’s, but a rival of equal stature and a political force on his own—and he wanted more.

By 52 BC the Senate had come to see Caesar as the biggest threat, and it sought a formerly unnatural alliance with Pompey. Two years later, Caesar demanded either a further extension of his now eight-year long governorship of Gaul or the privilege of running for a second consulship in absentia. The Senate, reassured by Pompey’s support, denied him both, and so in January of 49 BC, Caesar crossed the Rubicon and declared a civil war.

Caesar’s men adored their leader. Many of his lieutenants were new men who owed their entire careers to him. In the opposing camp, Pompey, who led the Senate’s forces, struggled to accommodate the unrealistic expectations of many self-serving nobiles, who felt equally entitled to lead armies, conduct war operations and have a say in all war councils. Some days before the decisive engagement—fought in Pharsalus, Greece, on August 9, 48 BC—Pompey had stated his intention not to offer battle to an enemy that was on the run, outnumbered, lacking provisions and trapped in hostile territory. Caesar’s army would surrender; they had only to wait. Pompey’s lieutenants loudly complained—surely, they hadn’t come all the way to Greece to avoid beating their hated foe in a glorious battle. Their general yielded to their entreaties—and lost the war.

Caesar had conquered Pompey and declared himself dictator. Unlike Sulla, though, he never intended to step down—he “had many Mariuses in him,” Sulla had once remarked. By February of 44 BC, Caesar had coerced the Senate into naming him ‘perpetual dictator,’ which made him king in all but in name. His absolute dominion over the State would forever hinder other men’s climb to the top. Because of that, as many as sixty senators—former Pompeians and long-life Caesarians alike—conspired against and ultimately murdered him on 15 March.

Caesar’s assassins—famously led by Gaius Cassius Longinus and Marcus Iunius Brutus—resented having to pander to Caesar in order to hold office. The men whose promotion Caesar had thwarted all felt profoundly insulted, while those he favoured nevertheless believed they would have fared better in free elections. Some felt that holding office under a tyrant reflected badly on themselves. As Caesar began to bestow the once-prestigious consulship for the space of a few months, or even for a single day, his partisans would have bitterly realised that briefly and nominally serving as consul under an all-powerful dictator was nothing they could boast about. Coupled with Caesar’s deliberate belittlement of the entire senatorial order, it certainly devastated the Roman elite’s perception of their self-worth.

Caesar had to be removed, and so they removed him—categorically.

Caesar’s last will had named his niece’s 19-year-old son, Gaius Octavius, as his main heir, and it posthumously made him his adopted son. As per the naming conventions of his time, the lad was now Gaius Iulius Caesar Octavianus—i.e. Octavian.

Octavian aimed to avenge his adoptive father, although to achieve that end he had first to follow a tortuous path that forced him even to cooperate with Caesar’s murderers against Caesar’s lieutenants—Lepidus and Mark Antony. He did so in order to fool the Senate—and particularly the aged Marcus Tullius Cicero, who was now leading it—into giving him an official position within the military, following Pompey’s earlier precedent. Having achieved that, Octavian then coerced the Senate into allowing him to run for consul at the insulting age of 20. Elected by a Caesarian mob, he immediately made peace with Antony and Lepidus, and he convinced them to join in as partners in a novel form of tripartite dictatorship—the triumvirate.

The triumvirs then resolved to murder anyone suspected of opposing them. Some of the targeted men managed to flee to the East, where Brutus and Cassius had gathered a massive army. They were seconded by the scions of noble families, who understood that they could only follow in the footsteps of their fathers if the old Republic was restored and the monstrous triumvirate, ousted.

Sadly, Brutus and Cassius were defeated in the battle of Philippi, fought on October 42 BC. It was the death knell of the Republic. The Mediterranean world was then divided among three despots. Early on, Lepidus was side-lined, and in 36 BC, Octavian unilaterally brought him down. The final showdown between the two remaining contestants took place in Actium, Greece, on September 2, 31 BC. Having been defeated alongside his lover, the Egyptian queen Cleopatra, Mark Antony fled to Alexandria and committed suicide there in August 30 BC, leaving Octavian to be sole ruler of the Roman world.

Allegiances during this accursed decade were neither decided by principle, nor by the prospect of promotion, but according to the chances of survival—one man courted Octavian’s yoke in Rome fleeing from Antony’s deadly grudge; another prostrated himself at Antony’s lover’s feet in Alexandria trying to escape from Octavian’s retribution. After Actium, all of them were at the conqueror’s mercy. The ranks of the nobiles were widely depleted, and they had to accept the apparent fact that Octavian’s straightforward monarchy was to be Rome’s new system of government.

In January 27 BC, however, Octavian seemed to relinquish his monarchical hold over the Roman State and pretended to devolve all power into the Senate and the people. Days later, he took up a new name—Augustus. Up to 23 BC, he continuously held one of the yearly consulships, but afterwards refused any claim to that office. This doubled any aspiring politician’s chances of serving as consul and showed that Augustus understood very well the philotimic drive of the Roman elite; he was already looking to exploit it to further his own ends.

The show he had made in 27 BC about relinquishing his dominion—coupled with the propaganda he had issued, loudly advertising a pretended return to the old Republic—proves also that Augustus had grasped how important it was to signal that he could—and supposedly did—step down. In this, he professed to follow Sulla’s example, not Caesar’s.

It had been his adoptive father’s deadly mistake to openly and flagrantly interpose himself in the path of his peers’ ambitions, seeming even to derive a mischievous pleasure from making the haughty nobiles feel insecure, worthless and inconsequential. It had been as foolhardy a policy as blocking the steam outlet of a pressure cooker—the pressure being the philotimic drive of the Roman elite, and the outlet, the satisfaction of such drive.

Augustus had learned from Caesar’s mistake, and from the moment he obtained absolute power he made sure to carve a way out for the pressure inside the cooker. He wanted the Roman elite to feel that they were worthy, important and still played a key role in government—and exploit their conformity to gradually cement his position as the first Roman emperor.

Augustus—that cunning alchemist of politics—had distilled the formula to successfully hijack the ‘philotimia’ of Roman politicians. A collective ideological-psychological drive that had helped preserve a Republic for hundreds of years, now contributed in laying the foundations of the 500-years long autocratic rule of the emperors.

That was the tragedy behind the fall of the Roman Republic.