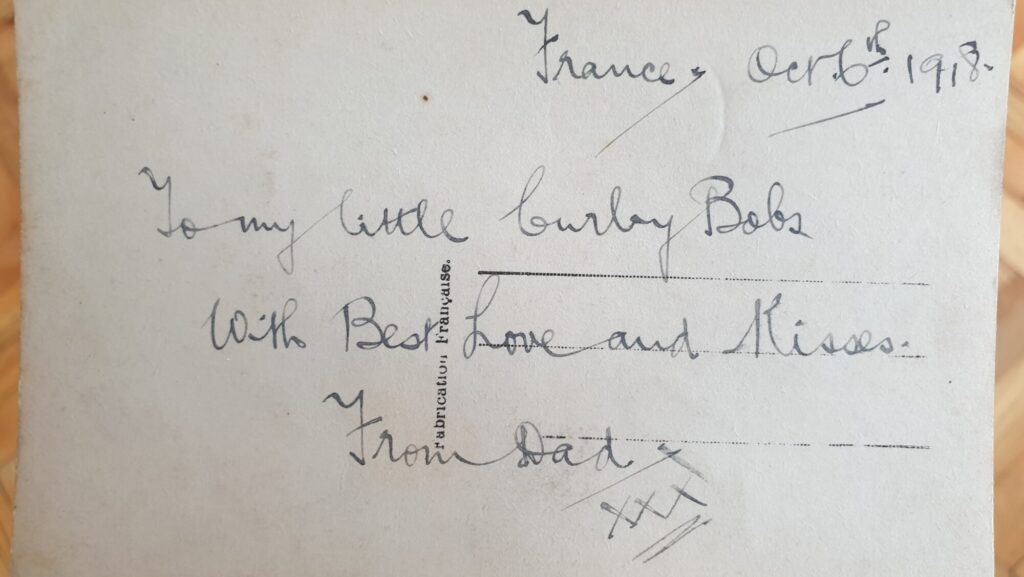

The postcard from a father to his son, Burly Bob. Courtesy of the author.

The work of Dalmacio Negro Pavón reveals that politics cannot be understood without anthropology: the various conceptions of humanity throughout history are not mere theories but paradigms that have shaped the lives of peoples and conditioned political thought.

Attempting to expound someone else’s thought is always a high-risk endeavor. But since I recently declared Dalmacio Negro Pavón the most significant political thinker in Spain in recent decades, with all due caution, I will outline what I consider to be some of the interpretive keys to Negro Pavón’s thought.

Last summer at one of Istanbul’s markets, I noticed a table with antique items. The Kurdish seller told of his goods: old postcards, bronze statues of elephants, lions, and horse riders, rare historical stamps from around the world and more. As I looked through the album I was suddenly struck by excitement. Among the postcards, there was one written from a father to his son and sent from Paris during World War I. In a matter of moments, the postcard had moved from the table to my backpack. Later that evening, I had the chance to examine it thoroughly, and doing so has helped me to understand the immense power fathers wield in periods of turmoil and death.

The postcard was dated October 6th, 1918. This was during the Hundred Days Offensive, a series of Allied onslaughts against the Germans from August 8th to November 11th, 1918, which marked the final push to end World War I. During this period, the Allies made significant advances against the Central Powers, culminating in the breaking of the Hindenburg line. By early October, the Allies had made substantial gains, including the breakthrough at the Second Battle of Cambrai on October 8th. The father who sent the postcard was likely navigating the turbulent final stages of the war while living through the epidemic of Spanish influenza in Paris.

It is also probable that this postcard was written by an English-speaking ally of the Entente (either an Englishman, Canadian, Australian, or New Zealander). His occupation could have been connected to anything from army service and medical work to diplomacy, journalism, or entrepreneurship. It is possible that by the time the child received the postcard, the war was already over. Whether the father’s stay in Paris was directly linked to the war or not, he was definitely influenced by it. There was a sense of grief for those who had died, hatred toward the enemy, fear for his life, uncertainty about the future, longing for his family, and angst at the prospect of never seeing them again.

In the midst of fumes of death, having woken to a new day of October 6th, he writes a brief letter to his son: “To my little burly Bobs. With Best Love and Kisses. From Dad. xxx.” He writes the letter on the postcard with a beautiful, colored image of a bouquet of flowers—and sends it.

The circumstances bring the letter into a different context. The message is brief, barely enough to learn of the man’s whereabouts, but enough for his family to sigh in relief—he is alive and well. The father reminds Bob of his strength; he is burly—large and strong! Yet still little, a spot of tender love in his father’s heart. He reminds little Bob of his love, kisses, and strong hugs. There is no war inside that embrace, just the smell of wood, iron, and sweat. The smell of confident serenity.

This confidence is hardly achieved. G.K. Chesterton once said: “The true soldier fights not because he hates what is in front of him, but because he loves what is behind him.” While patriotism and love for one’s nation are definitely factors that drive a man to leap into danger, the truest, most profound expression of love is towards his family. There is no horror as chilling as the thought of an armed enemy hurting your loved ones. There is no endurance as strong as the one that roots itself in the attachment to one’s own flesh and blood. This devotion overcomes a natural fear of death, suppresses the survival instinct, and teaches the mind to be cool in the heat of danger. And in the midst of distress, the father would still be able to support his burly Bob.

When the full-scale invasion of Russia into Ukraine started on February 24th, 2022, my father, a sonographer, was ordered along with his colleagues by the hospital administration not to leave their place of work. It was necessary because the government expected an influx of wounded people at any moment. As a result, my father lived in the hospital for 56 days, until the Russian army was pushed back from the Kyiv region. One of the first cases he handled was a woman who had been shot with a bullet in her hip, and after that, all the visits in his office blended into a kaleidoscope of lives directly or indirectly affected by war.

I visited my father a few times between curfews, while the noise of the siren pierced the sky, and occasional thumps of air defense hit the enemy’s targets overhead. We would savor the taste of freshly brewed coffee and talk of war, with the amalgam of caffeinated beans, cleaning detergent, and ultrasound gel scents in the air. When the enemy’s planes encircled Kyiv’s skyline, he would tell me of the valor of the Ghost of Kyiv, the collective image of the pilots of the 40th Tactical Aviation Brigade. When the Russian army was terrorizing our borders, he would describe to me the professionalism of our soldiers. When the face of Putin appeared in my imagination, he would remind me of the man’s mortality. And if my mind was still overburdened, he would brew another cup of coffee in the electric teapot and serve it with dried fruits.

His approach helped me, because I trusted his experience and judgment. Born in the USSR, he lived through the communist hellish ‘paradise’; observed Geiger counters go crazy during the Chernobyl reactor explosion; saw the end of the Soviet Union; lived through the economic collapse, the Orange Revolution, and Euromaidan; witnessed the beginning of war with Russia in 2014, and later the full-scale invasion of 2022; and still dared to make plans for the next Saturday to go to the theater! If he considered the art of Sholem Aleichem and Shakespeare worthy of traveling through the war-torn city, then there was definitely something to fight for. He could not stop the war from happening in his country, but he definitely tried to stop it from wreaking untold, irreparable damage on the minds of his daughters.

The minds of civilians are one of the main targets of the enemy. If they succeed in sowing fear and harvesting despair, then the war is all but won. With people distrusting the government and the army, there would be more protests and desertions, and above all—immobilizing pessimism, a cancerous tumor to any living hope. It prompted many defenders to hide their fear in the prayer room and tame their trembling voices. They joke while heating up military rations, exchanging news, training in how to use new equipment, and talking to their kids on FaceTime.

“When kids see that you are somehow holding on, they do too,” came the reassuring words of Gennadiy Mokhnenko, a military chaplain, pastor, and father of 41 (mostly adopted) children. “They imitate us. When they see our fears, they are afraid too. When they see Dad’s smile and cheerful words, then they do not give up. When they see that our hands fall and our hearts tremble, then they too are afraid.” Pastor Gennadiy fought many battles against death, rescuing the kids from its grasp. Back when Mariupol was free from occupants, he would go with the team climbing in the pits and under pipes looking for kids who were homeless and addicted to drugs. Under the roof of his Republic Pilgrim, many little souls received a second chance in life, while some relapsed and had their lives cut short. When Russia struck the city twice in 2014 and 2022, his team labored to evacuate children from imminent danger. Still today they are helping orphans and families in close proximity to the battleground move to safety, while providing humanitarian aid to locals and sharing the Gospel with the defenders.

Once, they went to evacuate a group of terrified children from one of the orphanages, while the Russian tanks were approaching the same location. When they were in the bombshelter and the noise outside was deafening, Mokhnenko loudly said: “Listen to me! The order has been given for Ukraine: lift up your noses! Everything will be fine! Ukraine will win! Now, how many push ups can you do?” It took just a couple of minutes, after which the kids loosened up and started to push up one after another, screaming: “I can do ten!” “I can do thirty!” The humor of the game helped them forget about the peril they were in.

When asked about the role of fathers during the crisis, Mokhnenko said: “Most of the atmosphere in the family depends on the father. If he keeps a positive mood, then the whole family will be ignited with positivity—wife and children. And if a man quakes in his boots, then everything will turn sour.” To explain what he means, the pastor said that the parent, either mother or father, is like a lead pilot helping a co-pilot to train. During the first flight, a co-pilot might often become disoriented during challenging situations and so, until he is trained, he cannot take full control of the aircraft. The time of war brings the ‘aircraft’ of life into many challenging situations, and kids often lose the ability to think clearly. If a parent chooses to abandon the cockpit or panics, the child will face the danger beyond his strength all alone.

Now, let’s say that the father of burly Bob decided not to send him a postcard from war-torn France. He forgot. He deemed it useless. He was too busy. He did not care. A little boy somewhere in the world would fall into thickets of hopeless imagination. He would grieve the possible reality of never seeing his father again or seeing him irreversibly changed by war. The dark fog of uncertainty would blind his eyes to see the beauty of small things: a colorful kite his uncle brought, steam rising from the freshly cooked brownie, a wagging tail of a spaniel, a perfectly round stone on the bottom of the bubbling stream. Reality for Bob—or rather, his perception of reality—would be determined by his mother’s hope and tears, the gossip of the neighbors, and theories of his peers as to when and how the war will end. Bob would often look down the road, where he saw his father last time, and every shadow resembling his dad would make his heart beat faster and faster, while suddenly dropping—and arms would fall to his sides, while his foot would angrily kick a stone on its way.

A father’s presence, both physical and spiritual, is impossible to overestimate. That letter from France, in the familiar handwriting of his Dad’s marbled hand, was an imaginative bridge to Bob from the dry land of despair to a promised land. A place where his youth would be protected, his explorative passions encouraged, and his masculinity shaped by the brave example of an experienced man.

The 1997 film Life is Beautiful masterfully shows the importance of fathers in times of calamity. Starring Roberto Benigni as the father, it depicts World War II, when the genocidal will of the Nazis swept over Europe, rounding up Jews into extermination camps to be exploited and killed. Guido, his wife, and their 5-year-old son Giosuè end up in one of the camps, unable to escape. To protect his son, both mentally and physically, Guido devises a plan. At one point, German officers come into the barracks demanding if any of the prisoners can translate from German to Italian. Guido volunteers, despite not speaking German. Standing in front of the prisoners—among whom is his little son—he begins to translate the officer’s instructions into his own version. “The game starts now!” he announces after the officer’s first instruction to the prisoners. “You have to score one thousand points. If you do that, you’ll take home a tank with a big gun. Each day, we will announce the scores from that loudspeaker. The one who has the fewest points will have to wear a sign that says ‘Jackass’ on his back. There are three ways to lose points. One: turning into a big crybaby. Two: telling us you want to see your mommy. Three: saying you’re hungry and want something to eat.”

Guido maintains this game for his son throughout their time in the concentration camp, despite the horrors surrounding them. At one point, when Giosuè hears that the Nazis burn some prisoners and make buttons and soap from others, the father loses composure for a moment. However, he quickly recovers and says, “You fell for that? Again? I thought you were a sharp boy … cunning and intelligent. Buttons and soap made out of people? That’ll be the day! You believed that? Ha-ha-ha! Just imagine. Tomorrow morning, I’ll wash my hands with Bartolomeo … a good scrub. Then I’ll button up with Francesco …” Then he pretends to unbutton his shirt and one of the buttons falls off. “Look!” he says, pretending to laugh, “I just lost Giorgio.” In a place daily visited by death, a gentle giggle from Giosuè broke through the clouds of fear.

Guido had no power over the will of the Führer. He couldn’t erase his Jewish identity or defend himself against the armored soldiers. However, he had another moment, another opportunity to influence his family’s reality. Even surrounded by the gas chambers, his son was safely hiding to gain points for the “game.” While other women grieved over their relatives, he found a way to reassure his wife that they were alive with the iconic “Buongiorno principessa!” Despite having no control over external circumstances, Guido asserted control over what was in front of him: his son’s trust and the power of words. He faced the imminent reality of death, calmed his fearful heart, and created a different, joyous reality for his little boy.

The Psalmist compares children to a quiver of arrows in the hands of a warrior. Properly aimed, an arrow will hit its target, bringing the desired result to the archer. However, placed in trembling hands, it will miss, flying chaotically. The example of fathers during times of calamity is similar to that archer. They can choose to surrender to fear, dragging their family down with them, or stand strong in the face of adversity. Just as the father sent his postcard to little burly Bob during World War I, as my father brewed coffee under the shelling, as Pastor Mokhnenko created a game for kids in the bomb shelter, and Guido created a game for his son in the extermination camps, today’s fathers are shaping the next generation. United in will and vision with their wives, they are able to confront unspeakable horrors, preserve their children’s gift for innocent wonder, and guide them toward a worthy aim.