“The Armenian leader Papasian considers the last remnants of the horrific murders at Deir ez-Zor in 1915–1916.” During the early period of massacres, 30,000 Armenians were encamped in various concentration camps outside the town of Deir ez-Zor. The photo is from the Arkivverket (Norwegian Archives).

The work of Dalmacio Negro Pavón reveals that politics cannot be understood without anthropology: the various conceptions of humanity throughout history are not mere theories but paradigms that have shaped the lives of peoples and conditioned political thought.

Attempting to expound someone else’s thought is always a high-risk endeavor. But since I recently declared Dalmacio Negro Pavón the most significant political thinker in Spain in recent decades, with all due caution, I will outline what I consider to be some of the interpretive keys to Negro Pavón’s thought.

The sun was shining on Istanbul’s Sultanahmet Square as I passed the gleaming white Obelisk of Theodosius and headed through the metal detector that guards the door of the Turkish-Islamic Arts Museum. It is a long building of rose-colored brick and stone, fronted by a row of high arched doorways lined with black bars and clusters of green bushes and the occasional palm tree. Built on the remains of the ancient Roman hippodrome, the building was restored centuries later by Sultan Suleyman the Magnificent as a gift to his grand vizier and childhood friend, Pargali Ibrahim Pasha who was strangled in 1536 when the sultan’s wife decided his influence posed too much of a threat to her own. But it was not this morbid history that I came to explore.

On April 24, 1915—Red Sunday—Minister of the Interior Talat Pasha gave the fateful order to hunt down hundreds of Armenian intellectuals throughout the city of Constantinople (renamed Istanbul in 1930). It was intended as a decapitation strike to devastate the Armenian leadership with a single blow, the opening act of the Genocide that would consume 90% of Turkey’s Armenian population.

Beginning at 8 p.m. and stretching through to the wee morning hours of April 25, Constantinople’s Armenian clergymen, doctors, journalists, lawyers, teachers, and politicians were jerked from their beds and locked up in the city’s infamous Central Prison. It took days for me to locate where, exactly, the Central Prison stands today. I finally discovered it in a 2013 Armenian Weekly article detailing a protest in front of the Museum during which the names of lost Armenian villages, swallowed by the crimson tide that followed Red Sunday, were listed defiantly through a loudspeaker. As it turns out, the Central Prison is now known as the Turkish-Islamic Arts Museum.

There was a fancy reception going on in the foyer when I entered, replete with chortling patrons stuffed into straining tuxes and solemn waiters gliding about with trays of expensive tidbits. Cameras were clicking frantically as I squeezed through the clusters of well-clad posteriors, passed through the sparsely stocked gift shop, and headed over to the enormous plaque affixed to the wall at the foot of the stairs leading to the courtyard. Tiny letters detailed the history of the Museum at length. There was no mention of it ever being known as Central Prison.

I combed the displays in exhibition halls accessible by low doorways lining the long brick corridors. I tried to imagine what the view of the imprisoned Armenian intellectuals might have been as I noted the woven rugs, the beautiful pottery, the ancient Korans. One section hosts Islamic relics, including a holy hair from the beard of the Prophet Mohammed himself. There was nothing, however, about the Museum ever having been a prison. Finally, I tracked down a staff member. There is nothing in the displays or on any of the plaques, I said. But is it true that the Turkish-Islamic Arts Museum used to be a prison? She looked at me quizzically, raised an eyebrow, and then nodded. “Yes. During Ottoman period.” That was as much as she would say.

Later, walking through the Blue Mosque with my wife, the mournful call to prayer began to sound from the minarets, echoing off the brick walls of the Turkish-Islamic Arts Museum. A thought struck me, and I asked a guide how long the Blue Mosque has sent the call to prayer out over the city. Centuries, she replied. Without a break? Even during the First World War? I asked. Yes, she nodded. Even then. I listened for a moment, and the call sounded sadder still. They would have heard it, I realized. In their cells, facing death—massacres of Armenians had already been taking place and several had been warned by sympathetic Turkish officials that this was coming—the imprisoned Armenian intellectuals would have heard the haunting call to prayer as they awaited their fate.

In that moment, they scarcely needed to be reminded to pray.

The Armenians are an ancient people, with the name Armenia said to be derived from Aram, their legendary ancestor and the direct descendent of Hayk, held in Armenian tradition to be one of Noah’s great-great-grandsons. According to the ancient Armenian historian Moses of Chorene, it was Hayk who defeated the Babylonian king Bel in 2492 BC and established the Armenian nation in the Ararat region, near the famous mountain where Noah’s ark had come to rest. Armenian roots in the region southeast of the Black Sea originate in the 7th century BC. Tradition tells of two of the twelve apostles, Thaddeus and Bartholomew, bringing Christianity to the Armenians between 40 and 60 AD. In 301, Armenia became the first nation to declare Christianity their state religion, an event marked by King Trdat III’s baptism by St. Gregory the Illuminator.

The Armenian Apostolic Church has existed independently of the Eastern Orthodox and Catholic Churches for over 1,500 years, and as a result has evolved into a major source of the Armenian identity. This is partially due to the fact that the Armenian church broke away from the other traditions in 451 AD over a dispute at the Council of Chalcedon, and also because of its centuries-long status as a Christian ‘island’ in a predominantly Muslim region. By the 16th century, the Armenians had suffered much the same fate as the rest of the Middle East and North Africa living under the rule of the Ottomans. Their status as a Christian minority made the Armenians both an object of suspicion and a convenient scapegoat. Pogroms erupted in 1890, 1893, 1895-96, and 1909.

I called Dr. Ronald Suny, emeritus professor of political science and history at the University of Chicago and Alex Manoogian Chair in Modern Armenian History at the University of Michigan, at his Michigan home to ask him about how the Armenian Genocide began. Suny, whose recent book “They Can Live in the Desert but Nowhere Else”: A History of the Armenian Genocide was hailed by many historians as a seminal work, has a personal connection with this history. His family fled to America to escape the massacres that foreshadowed the Genocide—his great-aunt had her throat slit by the Turks.

Suny has attracted the ire of both Turkish and Armenian nationalists for his attempt to disentangle the horrifying events of the Genocide from loyalties and emotions. To survivors and their descendants, attempts to explain why the Turks perpetrated these atrocities is to rationalize and perhaps even justify what took place. For many, the wickedness of the Turks is the only explanation for the sheer savagery they unleashed. Many Armenians see the stories of the Genocide as sacred: in Jerusalem in 2015, I stumbled on a beautifully sculpted cross of stone mounted in a courtyard adjacent to the Saint Saviour Armenian Convent. It did not speak of the victims of the Genocide—it was dedicated, instead, “In Memory of the Armenian Martyrs of 1915.”

Prior to the massacres at the end of 19th century, Suny told me, “Armenians in the Empire were relatively successful. Various Muslim groups competed with Armenians over land and resources, and conflicts developed. The government, instead of protecting their Armenian citizens, eventually allied themselves with the Kurds in their suppression of Armenians. Armenians began to resist this repression. They weren’t very powerful, but this brought a lot of fear on the part of the government. Eventually, the Turkish elites began to see the Armenians as a fifth column. They were foreign, even though they had lived there longer than the Turks.”

As the Ottomans lost confidence in their Empire, control had already been lost of their territories in Europe and North Africa. A cabal of military officers known as the Young Turks overthrew the Sultan and set up the Committee of Union and Progress, led after 1913 by the “Three Pashas:” Enver, Talat, and Djemal. With a skittish nationalist government in place, anti-Armenian rhetoric rising, and the external threat of the First World War looming, Turkey was a tinderbox. A single match was all that was needed to ignite a genocide.

That spark came with the Battle of Sarikamish in the Caucasus, which lasted from December 22, 1914, to January 17, 1915. Russian forces nearly wiped out the Turkish army, and panicked Turkish military officials claimed that Russian Armenians had fought against them. Turkish Armenians, they insisted, could not be trusted to fight for the Ottomans and were probably plotting to use the conflict as cover to create their own nation state. The leadership of the Young Turks cautiously agreed to cull Armenian soldiers from the main army and by April 1915 decided to deport Armenian civilians from any area close to military fronts.

The soldiers of the Ottoman Third Army were targeted first. They were disarmed, transferred to labor battalions, and taken in groups of a hundred to deserted places and shot or bayoneted. The Young Turks were increasingly paranoid, and any unconfirmed rumor of misbehavior by Armenians—even when they were simply attempting to defend themselves against sporadic violence by Turks and Kurds—was taken as evidence that the Armenians had to be dealt with before Turkish territory could be considered secure. Shortly after the defeat at Sarikamish, the American consul-general George Horton reported from Izmir that “lawless Turkish bands are appearing in increasing numbers in Smyrna district and are spreading a reign of terror among Christians of all races.” Suny surmises that special agents sent out by the Young Turks may have been behind the violence.

The deportation orders and spontaneous massacres occurred simultaneously. In Salmas, every Christian man the Ottomans could find was tied with his head through ladder rungs and decapitated. Ottoman statesman Resit Akif Pasa, who would later provide essential testimony on how the Genocide unfolded, noted that the “deportation order was given openly and in official fashion by the Interior Ministry, and communicated to the provinces. But after this official order was [given], the inauspicious order was circulated by the Central Committee to all parties that the armed gangs could hastily complete their cursed task. With that, armed gangs then took over and the barbaric massacres then began to take place.” In many places, the orders were used as a justification for pogroms, the settling of scores, or blatant ethnic cleansing.

In Constantinople, rumors of the ongoing massacres trickled back to the Armenian elites. The Armenian patriarch Zaven Ter Yeghiayan lobbied the government for protection and was given reassurance even as Ottoman officials resistant to the policies of ethnic cleansing were replaced with those eager to kill. When American ambassador Henry Morgenthau protested to Talat Pasha, he was waved off. “Our Armenian policy is absolutely fixed and nothing can change it,” Talat told him. “We will not have the Armenians anywhere in Anatolia. They can live in the desert but nowhere else.” With the soldiers neutralized and massacres and deportations in progress, it was time for a decapitation strike to eliminate the Armenian leadership with a single blow.

The 279 Armenian intellectuals—editors, physicians, clergymen, and politicians—arrested on Red Sunday were locked up in the Central Prison and at the police station. The second wave brought the number up to nearly 600, with arrests eventually totalling 2,345. Most were deported to camps surrounding Ankara and murdered. Many were first brought by steamer across the Sarayburnu from the Central Prison to Haydarpaşa railway station, where after a ten-hour wait they were sent by rail to their doom.

The train station is a restaurant now, a trendy place called Mythos. When I found it with my wife late one evening, we were greeted by a mustachioed concierge and ushered to a table. Afterward, we walked slowly through the dark station, reflecting on how those desperate men must have felt. It was eerie and silent, with rusty rail lines stretching off into the blackness. The station itself was shrouded in enormous plastic tarps for restoration, and it looked as if it were covered by a massive body bag.

With Constantinople’s Armenian leadership incapacitated, genocide began in earnest. The Young Turks justified their actions by claiming that killing the Armenians was a military necessity. The ensuing barbarism that would horrify even their German allies and force Talat Pasha to order that the bloated corpses littering Anatolia be buried was simply an unfortunate case of excess and enthusiasm. Regrettable, according to the Young Turks, but unavoidable.

The destruction of the Armenian people was savage and systematic. Muslims caught sheltering Armenians were shot in front of their homes, which were then burned. One Muslim leader, Cevdet Bey, became known as ‘the Angel of Destruction’ for the massacres that he perpetrated on the Armenians of the Eastern provinces. Witnesses reported hillsides carpeted with nude, bloody corpses, their throats weeping blood down their pale bodies. Entire villages were wiped out as Bey marched his men toward Bitlis. The men were executed, the women offered as war booty to the local Kurds. Rape survivors who would not convert to Islam were murdered.

In Bitlis, once a medieval Armenian kingdom, 15,000 were butchered. The men were shackled and hung; their bodies left as meals for roving dogs. In many places, Armenians were herded into barns and burned alive, while the women were forced to work as sex slaves for the Ottoman soldiers until they succumbed to brutality or venereal disease. Orphans who fled their killers were hunted down like rabbits and tossed in pits or drowned in the local rivers they had once played in. On the plains of Mus, once home to 141,000 Armenians, the men were almost entirely wiped out.

In some cities, the Armenians desperately tried to escape death by proving their loyalty. In the Black Sea port city of Trabzon, despite their protestations of fidelity, boatloads of shrieking people were towed out to sea and sunk. Armenian children in the city’s Red Crescent Hospital were poisoned. Dr. Mehmed Resin of Diykarbakir told his men that the “time has come to save Turkey from its national enemies, that is, the Christians. We must be clear that the states of Europe will not protest or punish us, since Germany is on our side and helps and supports us.” The Germans disapproved of the civilian killings but agreed that the Armenians posed a military threat. They chose to do nothing.

The carnage in Diykarbakir was hideous. Armenian leaders were beaten to death, and the British vice consul—himself an Armenian—reported that some “were shoed and compelled to run like horses…They forced some others to put their heads under big presses, and then by turning the handles they crushed their heads to pieces. Others they mutilated or pulled their nails out with pincers…Others were flayed alive.” Hundreds of infants were thrown from bridges. The bishop was doused with gasoline and set ablaze. The American missionary Dr. Floyd Smith found him dying in agony in the municipal hospital.

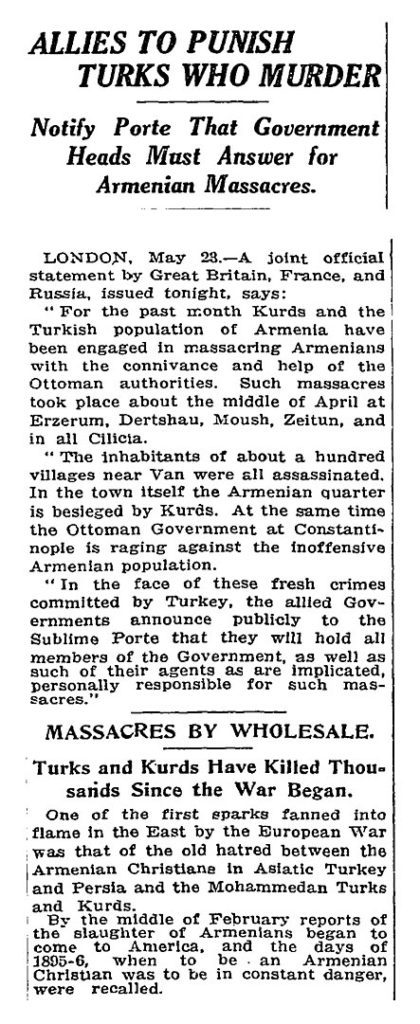

Reports reaching the West provoked outrage, and the Allies released a document on May 24 excoriating the Turks for “crimes against humanity”—the first time such terminology was used. The Turks ignored both condemnations and warnings of future reprisal. Between May and November of 1915, nearly all Armenians in eastern Anatolia were evicted from their homes, the men murdered, and the women and children marched in miserable convoys towards the southeast, heading for concentration camps in present-day Damascus and Iraq strung along the Euphrates into the Syrian Desert. Officials called it a ‘cleansing’ and a ‘purge.’ In Ankara, near the airport I flew into to begin my trip across Turkey, columns of Armenians were driven out of the city and hacked to death with axes.

The women and children were treated with utter cruelty. In many places, children were torn from their mothers and turned over to Turkish and Kurdish villagers for forcible adoption and conversion. (Many Turks today have Armenian ancestry for this reason.) Rape was ubiquitous on every forced march—the prettier women and girls were spared only to be distributed to villagers, and one Arab officer said that among many Kurdish soldiers involved in the sadistic sexual crimes “no man can ever think of a woman’s body except as a matter of horror instead of attraction.” Commanders gave their men carte blanche, and even children were raped—and then shot if they could not march on.

In one horrifying scene, soldiers threw children from the banks of a gorge and began assaulting the women—and were dragged to their deaths by women who pulled their tormentors over the edge with them. Suicide became common as the horrors mounted—in some places girls and women were stripped and crucified or vertically impaled. Many were abducted into the harems of the Turkish leadership, and women and children were displayed naked at slave auctions in Damascus, where sex trafficking became a source of income for soldiers. The miserable captive widows and orphans of murdered men glutted the market to such an extent that the German consul at Mosul reported that an Armenian woman fetched no more than “5 piastres.” Some converted to Islam out of desperation, seeking any escape from the boundless cruelty of their Turkish tormenters.

Even when the convoys reached the camps, the killing did not stop. One caravan of 18,000 had only 150 survivors after a scorching 70-day march through the Syrian Desert. Pregnant women gave birth on the road and were ordered to keep marching. In one camp, heaps of kerosene-covered kindling were used to burn 2,000 orphans to death. In another, 70,000 were allegedly burned alive in a single week. Some were herded into caves and fires set so people choked to death on the smoke. The atrocities were so numerous and so soul-wrenching Dr. Ronald Suny’s editors told him to remove some of the accounts from his book—there was simply too much evil for readers to bear. And yet, the Armenian people were forced to bear it all.

Not even the carnage of the Great War could cover up the enormity of the Turkish crimes. The New York Times reported in August 1915 of “a plan to exterminate the whole Armenian people.” Later that year, England, France, and Russia warned Turkey that they would hold the Ottoman government accountable for what was taking place, but nonetheless the killing continued into 1916 before it finally ceased. Over 1.5 million people were murdered.

In the post-war years that followed, Turkey’s new government was so tarnished by what had happened that they felt forced to set up military tribunals, and various leaders were charged with war crimes. Talat, Djemal, and Enver were sentenced to death in absentia. Somebody, it was agreed, would have to pay for what had been done so that Turkey could move on. The Great War had given modern Turkey its founding myth—Gallipoli—but it had also provided flimsy cover for the Turkish state’s original sin: genocide.

Talat was tracked down in Berlin by Armenian survivors and shot dead as he left his house on March 15, 1921. His assassin, Armenian Revolutionary Federation member Soghomon Tehlirian, was found innocent by a German court on the grounds that the trauma he’d experienced during the genocide had rendered him temporarily insane. Djemal was discovered by survivors in Tbilisi, Georgia the following year and similarly gunned down. Only Ismail escaped, dying later that decade battling the Red Army somewhere in Central Asia.

Over a century later, Turkey still denies that a genocide took place. The orgy of torture and murder, they insist, was only a series of unfortunate excesses perpetrated by over-enthusiastic but patriotic Turks neutralizing a very real military threat.

In 2021, the United States formally recognized the Genocide. Denial of the Genocide has been outlawed in France, Switzerland, Greece, Cyprus, and Slovakia. Only Turkey and Azerbaijan still resist the truth, and Turkey banned the use of the term ‘Armenian Genocide’ in 2017. The Kurds, on the other hand, have recognized their role in the genocide and apologized, giving rise to a strange alliance: As Suny put it, the Kurds now say that the Turks had the Armenians for breakfast and are having the Kurds for lunch.

The First Republic of Armenia was founded in 1918 after the Bolshevik Revolution, becoming a founding member of the Soviet Union in 1922. The modern Republic of Armenia became independent in 1991 when the USSR collapsed. For decades, survivors of the Armenian Genocide kept the stories of what their people endured forefront in the collective imagination of the Armenian people. Armenia, like Israel, is in many ways a nation born out of an inferno of destruction. An enormous museum commemorating the Genocide was opened in the Armenian capital of Yerevan in 1967, and world leaders regularly visit there on the anniversary of Red Sunday to pay their respects to the dead.

In Turkey, there were attempts just after the events of 1915 to commemorate the victims. In 1919, the Istanbul Armenian Genocide memorial was erected, a heartrending sculpture of people fading into the distance with a sobbing mother and child lying prostrate with grief at the marble base. It was erected in what is now Gezi Park near Taksim Square. During the Turkish National Movement in 1922, the monument was taken apart and went mysteriously missing. I walked past the darkened grounds of the nearby Military Museum and squinted through the fence at the premises littered with tanks, planes and statues. It was somewhere on those grounds that the base of the monument was last seen decades ago. It is probably gone forever: Turkey still makes war on memory and history, and her leaders have forced the Turkish people to enter a new century with the shame and stain of the unacknowledged Armenian Genocide hanging like a pall over their nation’s future.

Even speaking of the Armenian Genocide in Turkey can have deadly consequences. On January 19, 2007, the Turkish-Armenian intellectual Hrant Dink, who had been prosecuted for speaking about the Armenian Genocide, was shot three times in the head at point blank range as he returned to the Agos newspaper offices where he worked. Late one evening I walked the street where the offices once sat, searching for the spot where he fell. It is one of the busiest streets in Istanbul, and crowds of people flooded past me as I walked. On the night of his murder, heartbroken people slept on the street where he died, and over 100,000 people attended his funeral, marching through Istanbul with chants of, “We are all Armenians!” Thousands of people hung from their windows and tossed flowers onto the marchers below.

Men like Dr. Ronald Suny, whose book has been translated into Turkish, are doggedly pursuing the truth and presenting it to the many who are now ready for reconciliation. Men like Hrant Dink were willing to die to ensure that the truth be heard. Thus memory and history become a living thing, and the souls of 1.5 million murdered Armenians still haunt the Turks a hundred years later. The dead are long gone now–but the Turks will not be at rest until they acknowledge and repent for the evil they unleashed.