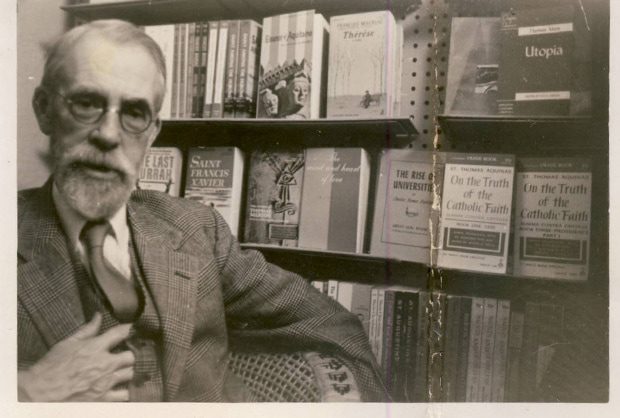

Christopher Dawson is an enigmatic character in the history of Western thought. No scholar of his generation was a greater champion of the idea of a united Christian culture, yet few were as sensitive to the problems such unity entailed. Although his influence waned after his death, Dawson’s reputation has been experiencing a broad revival, and his writings have begun to re-appear in updated editions. It is an apt time to reconsider this great historian and cultural critic—a giant of Western thought.

On 18 November 1889, Dawson was Christened in the Hay-on-Wye parish church by his grandfather, Archdeacon Bevan of Hay Castle. Hay Castle was a medieval estate built in the 12th century. The residence was extensively remodeled during the Tudor era, which gave it the atmosphere of a traditional English manor house. According to Dawson’s daughter, Christina Scott, Celtic legend holds that the castle’s origins stretch back much farther than Tudor times and associate it with “a figure called Maude of St Valery, mentioned by Giraldus Cambrensis in his Chronicles.”

No scholar of his generation was a greater champion of the idea of a united Christian culture

This house—now the site of the largest second-hand bookshop in the world—provided the ideal atmosphere for a young child to develop an active historical imagination. The young Dawson lived at Hay Castle for six impressionable years—exploring its haunted tower, wandering its secret passages, and gazing upon its ivy-covered walls with innocent curiosity. Hay Castle was a magical place, not only because of its supposed mythological foundation and architectural importance, but because of its location. There, in the Wye Valley, a mix of English and Welsh traditions combined to form a culturally vibrant, unique community.

At Hay Castle, the present was alive with the memories of the past, and each successive generation laid new chapters to its winding history. Here, shadows lingered, and Dawson was ever aware that he belonged to something beyond the mere moment.

Dawson inherited from his mother, Mary Bevan Dawson, a love for the Welsh countryside, along with a love for its people, its literature, and most of all, its saints. Dawson’s later understanding of Christian culture as something inextricably linked to the cult of the saints—especially in the Middle Ages—likely developed during this period.

Dawson’s maternal grandfather, with whom his family lived, was the vicar of Hay for fifty-six years. He was educated at Hertford College, Oxford, before his ordination and assignment to the congregation at Hay. While he never prospered from his position, the Archdeacon did leave a substantial estate upon his death; yet the Bevan children were reared in the manner typical of upper-middle class Victorians—“half an egg was considered quite adequate for a child’s breakfast for instance, while butter and jam were never allowed together.”

While his mother’s family was central to his early development, it is impossible to understand Christopher Dawson without examining the critical role played by his father, Henry Phillip Dawson. In 1886, Mary Bevan married Henry Dawson, Royal Artillery, whom she had met several years earlier. Both were approximately thirty-six and shared similar academic interests. Captain Dawson was more of an explorer than a soldier, and the closest he ever came to actual combat was behind the frontlines in the Franco-Prussian War, where he was an officer with his cousin, the Lord Kitchener of Khartoum. He had, however, been sent around the world to exotic places such as Cuba, and on a circumpolar expedition. Although Henry Dawson was dispatched to the Arctic to take magnetic readings, he spent much of his time conducting sociological studies of the Eskimo and other local cultures: especially important to his research was the impact of religion on primitive culture.

In 1896, the War Office ordered Henry Dawson to the command in Singapore. Instead of taking his family to a place he considered unhealthy and unfriendly, he retired from military service. He was promoted to the gentleman’s rank of colonel and moved the family to Hartlington Hall, his ancestral home in Yorkshire situated above the River Wharfe, between Burnsall and Bolton Abbey.

The land upon which Colonel Dawson would build Hartlington Hall had been in the family for over two centuries. Although the ancient house that had once occupied the property was demolished in the mid-19th century, the site was the ideal location to which Colonel Dawson could move his growing family. He wished to establish a country seat that could be loved by the generations—for Colonel Dawson believed, like Edmund Burke, in the “great mysterious incorporation of the human race,” in which the living, dead, and unborn exist in an unbroken communion. Tradition and family were paramount to Colonel Dawson and this, combined with Hartlington Hall’s location, forever influenced his young son.

Legends, myths, and religious belief

In Yorkshire, Dawson discovered the importance of legend and the immeasurable value of myth. Most important, however, was the Dawson family’s devotion to the Christian faith. With his sister, Gwendoline, Christopher began each day with prayers led by their father. These closely resembled the daily Office of the Catholic Church, which was unusual in late-Victorian England.

The young Dawson found great energy in the traditions of the Roman Church

The young Dawson was drawn to the idea of religion as a spiritual force that is active and participatory in every aspect of daily life. At this time, Dawson began to form his understanding that history and religion are closely linked. And although Mary Dawson harbored deep anti-Catholic prejudices from her upbringing as a conservative Anglican, young Christopher was captivated by his father’s keen interest in the Catholic Church.

The young Dawson found great energy in the traditions of the Roman Church, especially with respect to its liturgy, literature, and art. In later years, Dawson would discover the power of Catholic spirituality and become one of its staunchest apologists. Yet, at this early stage, Dawson’s attraction to Catholicism was developing more as intellectual curiosity: a spiritual awakening lay several years ahead, ultimately culminating with his entering of the Church on the Feast of the Epiphany in 1914.

At ten, Dawson was sent to school at Bilton Grange, near Rugby. His frail demeanor and “secluded childhood” were major disadvantages at a school known for roughhousing. Because of his poor health, Dawson’s academic success at Bilton Grange was limited, despite being an exceptional student in history and English.

In 1903, Dawson left to enroll at Winchester, where, although they did not meet, he was a schoolmate of Arnold Toynbee. Much to Dawson’s delight, Winchester Cathedral was a beacon of light. He would later write:

I learnt more during my schooldays from my visits to the Cathedral at Winchester than I did from the hours of religious instruction in school. The great church with its tombs of the Saxon kings and the medieval statesmen-bishops, gave one a greater sense of the magnitude of the religious element in our culture and the depths of its roots in our national life than anything one could learn from books.

It was at this time that Dawson began to read and collect books on a large scale. As he later wrote to a friend, he “got nothing from school, little from Oxford, and less than nothing from post-Victorian urban culture.” What he did learn he obtained from independent study, visits to various places, and from his life in the countryside with his bookish family.

One of the most important relationships Dawson would develop was with Edward Watkin, whom he met at 16, just before going-up to Oxford. Watkin would exert the most influence over Dawson during his university years and would eventually sponsor Dawson’s entry into the Catholic Church. But at the time of their meeting, Dawson was undergoing a brief period of agnosticism, and this made his initial meeting with Watkin—an enthusiastic Anglo-Catholic—“hardly auspicious for a future friendship.” (In fact, it resulted in a fist-fight, where Watkin smashed a garden chair over Dawson’s head). But in the end, it was Watkin who helped guide Dawson back to the Christian faith.

It was the confusion of authorities in the Anglican Church that led Dawson to briefly abandon the faith. At the depth of his agnostic confusion, he wrote that the only thing he could be sure of was his own existence. Anglo-Catholicism had proven to be weakest, for Dawson, where it had claimed to be the strongest: there was a lack of central authority, while a small group that lacked any power of enforcement determined all matters of orthodoxy. But by 1908, Dawson “resolved his doubts” and returned to Christianity. He and Watkin would thereafter remain close friends.

A return to Christianity

Dawson’s return to Christianity was fueled by a sense that he could not “acquiesce altogether in a view of life which left no place for religion.” The absence of religion left a “gap” in his personal life that could not endure. Although the lack of authority in Anglo-Catholicism once drove Dawson to harsh skepticism, he found it necessary to find some spiritual satisfaction that speaks to a higher level than the pure intellect. From the time Dawson was a young teenager, he had known the historical realities of Catholicism, but he did not know the Faith as a spiritual enterprise. His early exposure to the lives of the saints, medieval mysticism, and ancient lure had left him wanting some spiritual satisfaction—but the young boy did not yet possess the tools to fill the void.

But when he was nineteen, Dawson traveled to Rome. Overcome by the power of Baroque culture, Dawson found himself in an atmosphere that was conspicuously different from the Anglo-Catholic culture he had known in England. In Rome, Dawson came to believe that Catholicism was not merely a relic of the Middle Ages, but a dynamic faith and culture that had the power to shape the world. The Counter-Reformation was alive in Dawson’s mind, and he turned to the literature of St. Theresa and St. John of the Cross, both of whom Dawson believed to be of higher quality than any of the great non-Catholic writers.

Dawson loathed the standard modern-history curriculum

But it was through intense study of St. Paul and St. John by which Dawson came to a deep understanding of the unity of the Catholic faith. He began to see the significance of both the Trinity and the Incarnation, and more importantly, the primacy of the sacraments and how they provide cohesion to the whole fabric of Catholicism. The life of the saint became more than a mere account of mysticism or moral uprightness: it became the exemplar of the “perfect manifestation of the supernatural life which exists in every individual Christian, the first fruits of that new humanity which it is the work of the Church to create.”

While at Oxford, Dawson loathed the standard modern-history curriculum. Fortunately, Dawson’s tutor, Sir Ernest Barker, was a political scientist and historian of “strongly individualist character” and of diverse interests who, unusually at Oxford, encouraged his studies to focus on larger philosophical questions. However, at Trinity, he was “painfully shy” and socially unsure. Although from a public school and a member of the land-owning class, Dawson had no time for the snobbery or pettiness that could be characteristic of early 20th century Oxford.

A significant part of Dawson’s decision to convert was provided by his reading of the influential Catholic philosopher and writer, Baron von Hugel, which solidified Dawson’s interest in comparative religion. But it was the writings of St Augustine, particularly the City of God, that had the most enduring impact upon Dawson’s mind. Catholicism soon became a living faith for him, and Dawson, who had little active interest in becoming a Catholic, found himself drawing closer to the Faith. Watkin, his close friend, had converted during his first year. Dawson’s decision in 1913 to “go over to Rome” was not easy, and reminiscent of the conversion of John Henry Newman. Like Newman, Dawson believed that Anglicanism was unsatisfying because it lacked a unified structure. Cardinal Newman’s view reflected Dawson’s:

There were but two paths—the way of faith and the way of unbelief, and as the latter led through the halfway house of Liberalism to Atheism, the former led through the half-way house of Anglicanism to Catholicism.

Dawson’s conversion to Catholicism is illustrative of his distaste for revolutionary ideas. As he would later write, the Protestant Reformation was a “classic example of emptying out the baby with the bath.” He continued:

The reformers revolted against the paternalism of medieval religion, and so they abolished the Mass. They protested against the lack of personal holiness, and so they abolished the saints. They attacked the wealth and self-indulgence of the monks and they abolished monasticism and the life of voluntary poverty and asceticism. They had no intention of abandoning the ideal of Christian perfection, but they sought to realize it in Puritanism instead of Monasticism and in pietism instead of mysticism.

Upon leaving Oxford, Dawson was unable to pursue military service because of poor health, and instead, spent the next fourteen years voraciously reading a wide body of literature. He also fell in love. But the intellectual and spiritual energy required for his conversion, combined with his engagement to Valery Mills, almost caused Dawson to have a nervous breakdown. Valery’s mother did not fully approve of their marriage because of Dawson’s frail nature, while Dawson’s own mother and sister—devout Anglicans—did not approve of his new, Catholic wife. This issue was never fully resolved.

An independent scholar

Dawson rarely held formal academic positions. He was, between 1925 and 1933, Lecturer in the History of Christianity at the University of Exeter—an unfulfilling position, but one that allowed him to concentrate on serious writing and research. Fourteen years passed before Dawson published his first major work, The Age of the Gods, in which he began his historical inquiry into the nature of religion and culture. While Dawson planned to write a series of books on the history of culture called The Life of Civilizations, plans that were never fully realized, several intended projects did come to full fruition. Progress and Religion, widely considered to be his most important book, was intended to be a summary of the whole project. Other books included the proposed “third” entitled The Making of Europe, while the last—a posthumously published examination of the French Revolution—was called The Gods of Revolution. It was Dawson’s opinion, however, that his two Gifford Lectures delivered at the University of Edinburgh, and later published as Religion and Culture and Religion and the Rise of Western Culture, most fully illustrated his understanding of history and culture.

The Harvard appointment was unforeseen

The secluded nature of Hartlington Hall, which he inherited upon his father’s death in 1933, combined with poor health, forced Dawson to move his family from Yorkshire to near Oxford. He then spent four years in America as the first incumbent of the Charles Chauncy Stillman Professor of Roman Catholic Studies at Harvard University. The Harvard appointment was unforeseen, but after finding no suitable American for the job, Harvard wanted Dawson. The dean of the Divinity School, Douglas Horton, wrote to him with great pleasure and enthusiastically offered Dawson the position. Archbishop Cushing of Boston was no less excited. Horton wrote:

We appeal to you as a son of the Church. Never before in the history of the United States has there been anything resembling this professorship—a chair in Roman Catholic Studies in a university divinity school Protestant in tradition and Protestant in outlook.

Dawson accepted the offer, but responded to Horton’s request with a note of combined caution and optimism:

Of course I do not feel that I am competent to cover the range of studies that you outline in the third paragraph of your letter. But for some years now I have been feeling that there was a need for a fuller study of Christian culture than has hitherto been found in our higher education.

Dawson was excited about this appointment as he thought that the battle for the preservation of Christian culture was shifting from Europe to America. It was in the United States, he believed, that the fate of Christianity would ultimately be decided. Although America was the seat of technological culture, it was also the home of a vibrant Roman Catholic renaissance that gave hope to the prospect of a wide-scale spiritual resurgence.

Dawson maintained numerous literary friendships. Most important was probably that between he and Watkin, but other relationships are worth noting. T.S. Eliot was greatly influenced by Dawson, and Dawson’s ideas are found sporadically in Eliot’s writings, especially Murder in the Cathedral, as well as “Four Quartets,” and possibly in The Waste Land. Eliot acknowledges his debt to Dawson in Notes Toward the Definition of Culture and requested Dawson begin contributing to the Criterion and in the development of other projects. Additionally, as argued by Brad Birzer, it is likely that C.S. Lewis’s understanding of the Tao in the Abolition of Man is the result of Dawson’s discussion of natural law in Progress and Religion.

Like Eliot and Lewis, Dawson believed that the West was headed toward spiritual and cultural collapse. He thought that the best way to avoid such a catastrophe was for the West to return to a unity based upon its Christian heritage. Here, Catholics possesses a particular responsibility:

They are not involved in the immediate issues of the conflict in the same way as are the political parties, for they belong to a supranational spiritual society, which is more organically united than any political body which possesses an autonomous body of principles and doctrines on which to base their judgments. Moreover, they have an historical mission to maintain and strengthen the unity of Western culture which had its roots in Christendom against the destructive forces which are attempting its total subversion. They are the heirs and successors of the makers or Europe—the men who saved civilization from perishing in the storm of barbarian invasion and who built the bridge between the ancient and modern worlds.

Reaffirming Christian principles

The overarching theme in Dawson’s writing is unity. The world, to Dawson, was not an artificial place that could be created and recreated through abstract planning. This was the root of his problem with both revolutionaries and those who place their faith in technology. Dawson distrusted those who believed they could dismantle generations of organic cultural growth only to replace it with some “better,” rationally constructed system.

Dawson attempted to enliven the debate by insisting that something beyond politics was at stake

Dawson believed the Second World War to be the result of “discordant” cultural forces that had been building for centuries and he would write often in support of the Allied cause. He soon found himself in the unusual position of polemicist: he was, for a short time, editor of the Catholic journal, The Dublin Review, and vice-president of the Sword of the Spirit—a movement formed by Anglican Bishop George Bell to rejuvenate Christian spirituality in the wake of the war.

Dawson hoped that his emphatic stance against Nazi ideology would awaken his readers to the idea that the crisis was not merely political or economic, but the result of a growing spiritual vacuum. In The Judgment of the Nations, often heralded as his best book, Dawson attempted to enliven the debate by insisting that something beyond politics was at stake. In Religion and the Modern State, Dawson raised the discussion to the next level when he suggested that “biblical Israel,” which was both spiritually strong and materially weak, could triumph through its obedience to God. Conversely, the attempt to build a “New Jerusalem,” a heaven on earth—the goal of the Nazis—was the cause, he argued, for the unwitting creation of a terrestrial hell.

He produced other important works including Understanding Europe (1952) and The Movement of World Revolution (1956), before spending the remainder of his years dedicated to educational reform. In 1961, he authored The Crisis of Western Education, in which he maintained that the most effective way to combat secular ideology was through a reaffirmation of Christian principles through a program of Christian studies.

The prospect of a secular culture deeply disturbed Dawson. He believed the political and economic failures of his day were the product of a failure of the spirit. His injunction against secularism—and his warnings against an idolatrous faith in either the individual or the state—are his most enduring contributions to Western thought. We neglect Dawson at our own peril.