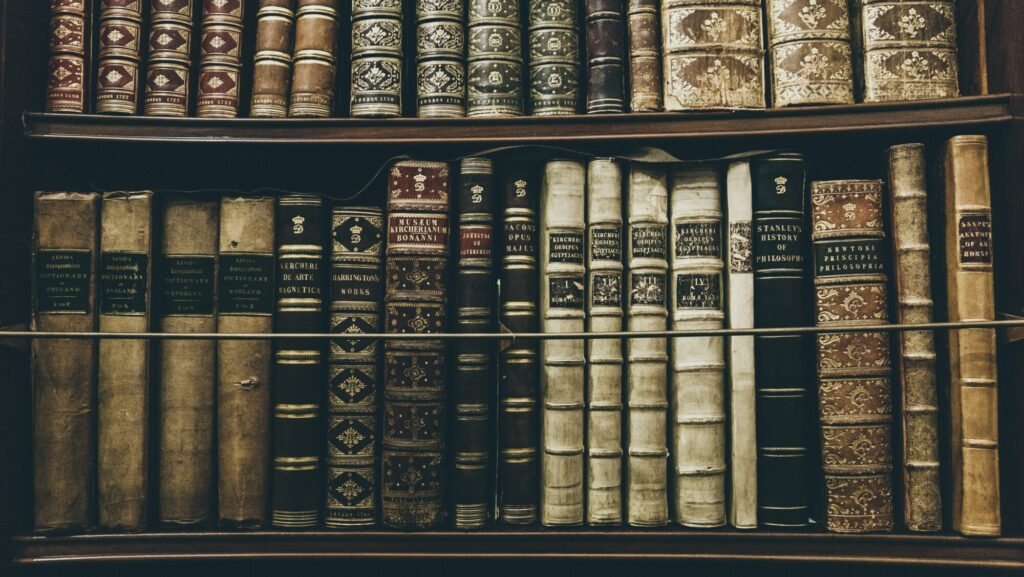

A sample of old books meant to last, in contrast to the current flimsy paperbacks. Found at Chatsworth House, Bakewell, United Kingdom.

The work of Dalmacio Negro Pavón reveals that politics cannot be understood without anthropology: the various conceptions of humanity throughout history are not mere theories but paradigms that have shaped the lives of peoples and conditioned political thought.

Perhaps it is because I grew up in a house without a television that I cultivated a great love of books from an early age. Or, perhaps it was the serious Protestant atmosphere in which books were venerated—I still remember the anger with which an acquaintance responded to finding a Bible lying on the floor—that laid the foundations for the way I treasure them now. Either way, I was very fortunate to be surrounded by exactly the sort of books that I would wish for my own son to have, not only in content but in quality of production. I remember a giant red and blue two-volume history of the world in which—at least in the second volume—almost every year of history had a two-page spread. Not only was the content fascinating, but the huge hardcover binding left its own tactile impression on me. To be in the book was to enter into its physical structure as well as its intellectual content. Too large and heavy to rest on my childish lap, I would lie prone on the floor for hours leafing through it, discovering the unfolding of history year by year. I wish that I could remember the name of this series.

In adulthood, this love transformed into a habit of book collecting which far outstrips my reading capacity. I know that I am not alone in experiencing both the delight of buying a book whose contents I greatly desire to read—yet not right now—and also the almost equal delight of rediscovering that work years later when something in its content happens to be directly relevant to a rather niche query which is plaguing me.

In many ways, it is my delight that in recent years there has been something of a renaissance in the Catholic publishing sphere. Firmly established—yet still relatively new, in publishing terms—purveyors of stimulating texts such as Angelico Press are now joined by newcomers such as Cluny Media, Arouca Press, Loreto Publications, Cor Jesu Press, Os Justi, and the Tradivox project. This circle of book restorationists join the first generation of post-Vatican II publishers like Tan Books in an effort to contribute towards what St. John Henry Newman called an “educated laity.” Angelico Press in particular brings an astonishing breadth of learning and subject matter to its offerings, featuring the whimsical yet deep fiction of David Bentley Hart, esoteric Catholic investigations into the laws of time, the penetrating mystical Catholic classics of Jean Hani, books on how to make medieval clothing, and translations of Russian Sophiologists. Truly a heady mix and some of the books which Angelico puts out may hold the key to breaking out of the devastating civilisational and ecclesiastical crises which beset us. I do not exaggerate their importance, for many of the contemporary Catholic Church’s most penetrating minds have indicated their debt to these works. More modest—yet important—contributions are being made by the other publishers mentioned. The Flowering Hawthorn by Hugh Ross Williamson, published by Arouca, is an example of a book that I would recommend to every English Catholic. Thousands of pounds worth of books from these publishers can be found in my library, yet there is another commonality that each of these publishers share, and it is a less flattering aspect: disappointing print quality.

It may be worth taking a brief detour into the history of book publishing and particularly the debt it owes to Catholic civilisation. As with most great civilisational inventions, bookbinding was not invented by the Christian West; codices have been discovered at Nag Hammadi and a comparable format of bookbinding was present in India during the 2nd century BC. Yet it was in the West that scrolls and wax tablets were properly supplanted by the Codex. Motivated by the supreme spiritual dedication to the Holy Scriptures which has been a feature of the Christian religion from its earliest period, monks created a vast network of book copyists and producers across the entire European continent and beyond. Men and women abandoned all in order to dedicate themselves, come plague or war, to transmitting the Word. Bibles held such value that they needed to be chained to their churches. Gold and precious stones would adorn the covers of the Gospels, and up to 2,000 head of cattle could be used to produce enough vellum for a complete biblical codex, an almost unimaginable exercise of wealth for a single book. Perhaps no other civilisation has such a detailed record of its historical course as that of European Christendom, due in part to its bookmaking. The course of its history, marred by war with the sword and the gun, has been equally marred by war with the pen. The Reformation is first among them, being fought on both corporeal and literary battlegrounds. If any other civilisation has such an illustrious history of bookmaking, there is little record of it now. However, this returns me to my major criticism of the Catholic publishing renaissance: its poor standard of bookmaking.

As I peruse my library pulling out many of my favourite Catholic texts, it is clear that they will only last more than a generation if they remain unread. Most, if not all, of these publishers now make use of the print-on-demand system which has come to dominate much of the independent publishing overseen by our literary overlords, Amazon. These books appear primarily to be held together by glue, making them rather difficult to hold open and giving them a particularly fragile constitution once the spine is properly worn in by the reader. Gone are the days of beautifully stitched bindings, of hardcovers which open ever more naturally with use. In their place come hardcovers which appear to be little more than softcover books glued to a ‘hard’ cover. Of course, this is also a problem in the wider publishing industry. I recently bought a copy of Ficino’s On the Christian Religion for an eye-watering £76. Despite having been published by the University of Toronto Press, it featured none of the tactile pleasure that one might have expected from a university press just 20 years ago. The handsome sum of its list price yielded only a mess of glue and inflexibility. Perhaps I expose my ignorance of book printing arcana when I express my perplexity at the contrast with the Harvard-produced Platonic Theology, also by Ficino, which, for little more than £19, has been bound and sewn to such a delightful standard that I must occasionally take it down to flick through its pages, simply in order to enjoy the subtle and refined rustle of each turning page.

But I digress. Some may object that the aforementioned Catholic publishers are rather small and cannot be expected to have the resources of Harvard University; and, they are doing their best despite the Kali Yuga of books in which we find ourselves. There was a time where I would have agreed with this point; however, I have recently become aware of a small but flourishing subsection of the book industry which lays waste to this claim.

Driven by my interests in Pythagorean and Platonist philosophy, I found myself stumbling upon some truly obscure publishers. Black Letter Press, Scarlet Imprint, Anathema Publishing, and Three Hands Press publish small numbers of highly niche, obscure texts dealing with the borders of religious thought, philosophy, witchcraft, and other esoterica. The books they produce are so obscure that they cannot even be found on Amazon, which famously sells just about everything. Yet as I browsed the titles of these occult bookmakers, I noticed one thing: they produce special editions of their works appropriate to their estimation of the content. Take for instance Anathema Publishing’s recent release The Search for Óðinn. As yet, there is no paperback edition, only a ’standard’ hardbound edition. Limited to 700 copies, this hardcover is the mass-produced option, featuring Colibri ‘Dolphin’ fine Italian book-cloth binding, and printed on Munken pure smooth cream 150gsm archive-quality paper. This is a book for book lovers. From here it only gets better: a collector’s edition, which I own, is bound in Wintan vintage granite-coloured bonded leather with gold foil blocking on the spine. Limited to 480 copies in all, this edition is still closer to the standard hardcover edition than the two different Artisanal editions. Those are bound in leather with raised bands on the spine—something almost unseen for generations—with a satin ribbon to mark pages. These are books that would not look out of place in a rococo monastic library. Split between 18K and 24K gold detailing, they are priced at more than £400 and are sold out almost everywhere. Secondhand versions are already selling for almost £1,000. Such phenomena are widespread in the niche world of collectible books, as can be seen in the fine and deluxe editions of Martin Duffy’s Effigy, Peter Mark Adam’s Mystai, and Christina Oakley Harrington’s Dreams of Witches. Many of these publishers have less than three dozen books and 15 years of experience under their belt.

My challenge to Catholic publishers is this: why not produce limited editions of your most excellent works in goatskin and gold detailing? Why not add beautiful illustrations, specially commissioned, to adorn the works—interior and exterior—and thereby to elevate the prose? Smaller publishers with smaller audiences are doing so: because their readers truly believe that the work deserves to survive for generations to come. The numbers also make sense: 30 copies of an artisanal edition—produced to the highest book-making standards—priced at £500/$600, alongside 600 copies of a collector’s edition at £130/$170, would pay handsomely. Catholic readership, even of the traditional kind, is surely larger than the exceptionally niche readership of a publisher such as Three Hands Press, and just as surely devoted to the material. Yet none of the works available to them, newly published today, will be on the shelves of our great-grandchildren; they will not be treasured as heirlooms or works of art in themselves but instead will need replacing within decades. Give us artisanal editions of Borella’s Love and Truth, and of Bugakov’s Spiritual Diary, lest copies of Aleister Crowley’s work be more likely to survive the next sack of Rome than those of Valentin Tomberg. Let not the pagan occultists be the last of the true book lovers.