Habsburger double-headed eagle at the Schönbrunn Palace in Vienna, Austria.

PHOTO: ARJAN RICHTER, CC BY 2.0 VIA FLICKR.

The invasion of Ukraine raises several long-term issues, far beyond the immediate. Not least of these is the position of Central Europe. Until Vladimir Putin’s decision to invade, both the actions of the Western elites and the Russian president’s own rhetoric over the past decade seemed to cast Putin in the role of the last defender of Christendom. He buttressed this verbiage with a sturdy defence of Christians in Syria and elsewhere. In comparison to many of their national leaders, Putin seemed a better example of leadership to many conservatives.

Perhaps the contrast was cast most clearly in October 2021 when, as described by Polish MEP Kosma Złotowski, European Commissioner for Equality Helena Dalli unveiled internal guidelines on “inclusive communication” for Commission staff, detailing phrases to be avoided. In addition to terms related to gender and sexual orientation, the list also included terms related to Christianity, such as Christmas and the names Maria and John.

Despite the promise that these regulations would be “revised,” Złotowski observed:

[T]he very fact that this grotesque document calling for discrimination against religious people has been the subject of Commission work and has been presented by the Commissioner for Equality is scandalous.

Indeed. Moreover, it is a clear indication of the gulf within the EU between Central Europe’s and Western Europe’s leadership—and, for that matter, between the former and our own American elites. With ‘wokery’ triumphant, Putin began to appear, to many, as a possible patron of sanity in Europe.

This, however, ended with the Russian invasion of Ukraine. To be sure, some very good arguments, which this writer certainly understands, have been made to explain the paranoia of Russia toward the West. These include the alleged broken promises made at the time of the Soviet withdrawal that NATO would not expand to the borders of the old Soviet Union. Of course, what was specifically promised was that, during the period when East and West Germany were reuniting and joining the alliance, and both the Warsaw Pact and the Soviet Union were intact, NATO’s Command Structure would not move eastward. Later, it was further agreed upon that NATO would not place nuclear weapons in Central Europe—although Putin did so in Kaliningrad.

Regardless, this writer is reminded of the American entrance into World War II. By way of example, I will share a short family history. Both of my parents’ families (although they did not know each other at the time) were staunchly ‘America First’ and loathed Franklin Delano Roosevelt. When France fell in 1940, it came as a grave shock to the denizens of “Little Canada” in Massachusetts, where my father resided. It was only at his funeral in 1996 that I learned the story about how, at Mass the day following the French surrender, the then 14-year-old boy, seeing the dejected looks of his fellow parishioners, stood on a table and sang the Marseillaise. The fact that the following day was the feast of St. Jean Baptiste, patron of the French-Canadians, added poignancy to the scene.

But despite this unfortunate development, he and his family still strongly opposed our entry into the war, even though Hitler’s successes pained them. Afterwards, according to their way of thinking, FDR goaded the Japanese into war. Nevertheless, Japan did indeed fall for the bait. Regardless of whether or not Roosevelt withheld key information from the military command at Pearl Harbor, the Japanese did indeed attack.

My father volunteered to serve on his 18th birthday in 1944. Joining the Air Force, he became a tail gunner, chalked up 12 successful missions in the Pacific, and won the Air Medal with bronze oak leaf cluster. However, his attitude toward FDR did not change, and up to the end of his life, he believed that Roosevelt had entered us into the war to bring an end to the Great Depression.

The reason for dredging up all of this familial history is simply this: whatever provocations Putin faced, and however just or not his ire and contempt toward the Western leadership is, he did indeed invade Ukraine.

These developments put the Central European, or “Intermarium,” states into a strange position. On the one hand, Putin would indeed occasionally offer encouragement in various forms to politicians and public figures in these countries who were struggling to maintain the integrity of their cultures against the work of figures such as George Soros. On the other hand, the same experience with Soviet hegemony that has rendered them immune, at some level, to the kind of decadence Western leadership favors, also led them to suspect Russia’s intentions. This suspicion was certainly not allayed by the invasion of Ukraine.

All of these events point to the need for the Central European states to align more closely if they are to maintain their cultural and political integrity vis-à-vis Russia and the West. Of course, there are problems with achieving this sort of unity. These nations have a long and fractured mutual history, which has produced martyrs and heroes in each of them; although, often enough, the heroes of one people have produced the martyrs of others.

But amidst all the division, there have been periods of relatively amicable unity. In the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, Poles and Lithuanians—as well as Ukrainians and Belarusians—managed to get along for centuries, until their state was destroyed by the partitions of the 18th century. The heirs—though not the inheritors—of the Commonwealth’s founding dynasty, the Jagiellonians, were, of course, the House of Habsburg. Heirs to many other royal families as well, Habsburg at one time presided over an empire that literally spanned the globe. But most of their effort historically was among the peoples of Central Europe.

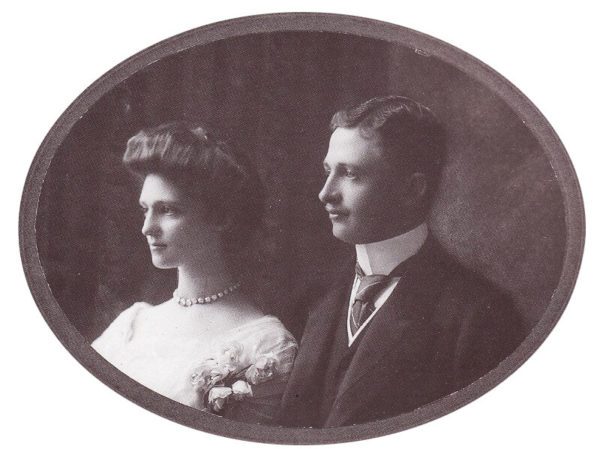

Until vivisected by the tragic events of 1918, the Austro-Hungarian monarchy (as the last incarnation of Habsburg state power was named) provided a functional and workable common home for at least 11 different nations. Defeat and exile awaited Blessed Karl of Austria, the last Habsburg Emperor, who died painfully of pneumonia in 1922, offering his sufferings “that my peoples might come back together.” On the road to Sainthood (Karl was beatified in 2004), veneration of his memory has grown in recent years in his former realms.

Karl’s son, Archduke Otto (1912-2011), took his inheritance quite seriously. Advising FDR during World War II, he was able to convince the president that Austria, too, was a victim; the result was Austria’s resurrected independence after the war. During his long life, he met most of the great political figures of his era and became an intensely perspicacious and knowledgeable commentator on political affairs. Interviewed by the Süddeutsche Zeitung in 2005, the Archduke noted that he had been observing Putin for a very long time, before anyone else thought him of interest:

[W]hen the last election campaign in the GDR was taking place [in 1990], I arrived at a Dresden hotel on a Friday evening. The director told me: “Don’t forget, the anti-communist demonstrations are taking place today.” It was feared that there might be shooting there. Of course I went there, and at this demonstration I met people who were let out of prisons where they also had dealings with Russians. And some said: there is a young Russian who is particularly bad. His name is Vladimir Putin. And I’ve been interested in him ever since, because nobody else was interested in him. This is an old KGB man who denounced his classmates in his own school. Look how much Russia has been re-Stalinized since Putin came to power, just look at the internal structure of the government, look at the emigration that Russia has again. Look at Khodorkovsky’s trial, which was a scandal.

Otto’s son, the Archduke Karl, has been speaking out about the mounting danger to Ukraine for several years. Just like his father, he is not a man who can be accused of supporting the sort of ‘wokery’ epitomized by such figures as Joe Biden and Justin Trudeau. When I spoke with him recently, the Archduke had just finished working on a documentary produced by his daughter, Gloria von Habsburg. Titled Navalny, it deals with the poisoning of the Russian opposition politician Alexei Navalny. Before production, Karl got to know Navalny—and what the Putin regime had done to him—very well. The Archduke met Navalny while the latter was in Germany recovering from the poisoning. Because Karl knew Navalny and had spoken a lot with him, the Archduke became a consultant on the film. Certainly, the experience reinforced his previous opinion of Putin. During our discussion, he told me, “I do not understand why so many conservatives like Putin.” I responded that both our Western leadership and Putin’s own rhetoric had cast him as the defender of conservative, Christian values. We then speculated on the possibility of a Russian invasion of Ukraine—speculations which have tragically been confirmed by real events.

Of course, the Archduke’s documentary work was distinct from his role as head of the House of Habsburg. His major involvement in political work is through the Paneuropean Union, an organization founded in 1922, for which his father, Archduke Otto, had served as president. Although the Pan-Europa Movement, as it is also known, had initially endorsed the European Union—in whose parliament both Otto and Karl served—today, Karl and Pan-Europa are quite clear as to how far the EU has departed from its explicitly Christian foundation. In a speech given on his birthday, January 11, the Archduke called on his audience to help regain the Christian soul of Europe, without which Europe cannot survive.

In keeping with his position as the head of a dynasty that has left such a deep mark on its former realms, the Archduke frequently presides over a number of cultural and historical events, which generally include participation by various historical reenactment groups, historical military units, and civic groups. To help him juggle these commitments, Karl maintains a Generaladjutantur, or ‘General Adjutancy’, much like those of his imperial ancestors before 1918. In addition to its central office in Vienna, there are regional adjutancies in several of the Austrian states, Czechia, Hungary, Italy, Prussia,, Slovakia, Slovenia, and South Tyrol. The green plumed members of this office ensure that each event transpires as it should.

Karl presides over several orders of chivalry: the storied Order of the Golden Fleece, of course, and the newer European Order of St. George. The latter order has commanderies throughout Central Europe. The Archduke also succeeded his father as head of the Knighthood of Saint Sebastian in Europe. This chivalric brotherhood, whose motto is For God—For a united, Christian Europe—For life, is itself a development of the European Association of Historical Riflemen. Founded in 1955, the latter organization encompasses shooting associations from Austria, Belgium, Croatia, Czechia, France, Germany, Italy, Liechtenstein, the Netherlands, Poland, Sweden, Switzerland, and Ukraine. Karl is also chief of the Academic Federation of Catholic-Austrian Landsmannschaften, an association of Catholic monarchist college fraternities. Karl also serves as patron of the Ordo Equestris Vini Europae, the European Military Parachuting Association, and the Blue Shield, which “works to protect cultural assets threatened by armed conflicts.”

Often joining with or in place of Karl at the events of these organizations is his brother, the Archduke Georg. Given the large number of commemorations and the like, it is just as well there are two of them! But George has a job of his own: after years of representing Hungary in international organisations, he has recently been appointed as Hungary’s ambassador to France. When presenting his credentials to French President Emmanuel Macron, the Archduke observed that he felt a little at home in the presidential palace, because “[m]y great-great-grandmother Louise Marie Thérèse d’Artois was born there. It was in 1819.” She was, of course, the granddaughter of King Charles X of France.

Their sister, Walburga Countess Habsburg Douglas, was instrumental in organizing the “Pan Europa Picnic” in 1989, which played a significant role in bringing down the Iron Curtain. In 1992, she married the Swedish Count Douglas, and sat in the Swedish Parliament from 2006 to 2014.

There are a number of branches of the House of Habsburg. One of these is the Hungarian branch, comprised of descendants of Archduke Joseph (1796-1847). Archduke Michael, one of its junior members, has lived in Hungary since returning in 1995, and has done much to work for the re-Christianization of the country. He heads the Cardinal Mindszenty Foundation, which is working toward the beatification of that saintly prelate. Michael’s son, Eduard, is Hungary’s ambassador to the Holy See, and has been active in informing the public about Bl. Emperor Karl, as has Archduke Rudolf, first cousin to Karl and Georg.

Indeed, the culti of both Bl. Karl and his wife, Servant of God Zita (her cause of beatification has also been introduced) have brought the veneration of the imperial couple back to the attention of the Central European public. The Gebetsliga—the organization working for Karl’s canonization—includes members not only in the Austrian states, but also in several other countries, including Czechia, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia. Similarly, Zita’s association has devotees in Austria, Croatia, Czechia, and Hungary. In this centennial year of Karl’s death, devotion to the imperial couple can only grow.

In addition to the innumerable cultural and civic groups throughout the old Empire that perpetuate various aspects of the Habsburg legacy in their own region, there are small numbers of professed monarchists in Austria, Croatia, Czechia, Hungary, Slovakia, and Slovenia. Indeed, Czechia, famous for its longstanding hostility to the Habsburgs, boasts a couple of monarchists in its parliament. In 2021, while cities were burning all over the United States, the Marian Column in Prague—torn down in 1918 as a sign of victory over the Catholic Church and Habsburg State—was re-erected. At the same time, the Double Eagle was restored at the fountain in Prague Castle, and permission was granted for restoration of the Radetzky Monument, also torn down in 1918. The Audienz at Brandys, an annual reenactment of the visit of Karl and Zita to their chateau in the town, always draws crowds of visitors from throughout the old Empire.

There can be no return to the past: Austria-Hungary is gone forever. But a close union or federation of the Central European nations as a check upon both Russian expansion and Western attempts at ‘woke’ cultural and irreligious domination seems quite plausible, especially in light of recent developments in Ukraine. But more is needed for such an entity to prosper than mere enmity. It needs something positive. On the one hand, the most important such factor is the area’s Christianity. But the Habsburg legacy, so visible from Tyrol to Transylvania, might also play a key role. As the Archduke Karl himself has stated:

People who say that monarchy is more of a form of government from the past are simply not being realistic. It is a form of government of the past, present, and future, just as other forms of government have played a role in the past or will play a role in the future.

Such a Central European federation could serve not just as an example, but as a catalyst for the rest of the continent. Without a doubt, the crisis of the modern world is really a failure; one resulting from a lack of leadership. This is a void that the Habsburgs may one day, perhaps sooner rather than later, find themselves called upon to help fill.