Hercules defeats the Hydra of Lern (c. 1613-1638), an engraving on paper by Charles David (1600-1638), located at the Rijkmuseum, Amsterdam

When it began, they probably thought that no one would bat an eyelid. That was in 2016, and the Woke revolution was still young. Black Lives Matter was in ascendency. A year later, a neo-Nazi protest in Charlottesville, Virginia, would inspire the beginning of the large-scale removal of Confederacy-linked monuments in the United States. With that, Pandora’s box was opened. But the preludes of that bitter struggle to come were already being played out on the shores of the Tagus. I happened to be a leading participant.

The provocation was straightforward enough. As the Praça do Império (Empire Square)—one of the largest public areas in Portugal and Europe—was geared for renovation, a Trotskyite-linked Lisbon city counselor, José Sá Fernandes, pompously announced that not everything was worth preserving. The topiary garden at the heart of the square was obsolete, he thought, not for any aesthetic or practical reason, but simply because it represented the coats of arms of the former Portuguese colonies. The reasoning was that, because Portugal no longer had any colonies, there was no motive to celebrate or memorialise them in public art. In his view, keeping it could be perceived as insulting, or even hurtful, by the peoples of modern-day Lusophone nations. Lisbon, hence, would be better off without such divisive displays.

We begged to disagree. Mr. Sá Fernandes’ fears notwithstanding, the truth is that no foreign state, Lusophone or otherwise, had ever made even the mildest complaint about the Praça do Império’s supposedly scandalous gardens. In fact, the opposite appeared to be the case: Portugal’s post-imperial Commonwealth copycat organisation, the Community of Portuguese-speaking Countries, had actually used the square for many group photographs of Lusophone heads of state and government, and none had ever objected. The notion that a topiary garden was somehow the object of international outcry was as ludicrous as the counsellor’s primary claim that ‘outdated’ history is not worth keeping. After all, history is outdated by definition: accepting Fernandes’ point that Portuguese imperial heraldry lost its raison d’être with the demise of the empire entails believing that no monument to a past polity, dynasty, or individual is acceptable. The idea was absurd.

Few were fooled—and, at Nova Portugalidade, we decided to fight back. As is the rule of Portuguese associative life, our group was badly lacking in resources, both human and financial. Media access was difficult: the country suffers from one of the most biassed, ideologically hostile, and vertically controlled press environments in Europe. Our chief weapon was common sense, and it worked. Faced with the looming outrage, we summoned some of the finest and most influential voices in politics and academia: historians and diplomats, artists and filmmakers, intellectuals from both the Right and the civilised Left, generals and royals. The people listened: thousands signed our petition opposing the removal of the imperial symbols. Fernandes and the Left were horrified.

Sensing the shifting winds, the anti-history fundamentalists struggled to spin the narrative. Even though he had freely confessed to the opposite, Fernandes then claimed—to everyone’s bafflement—that the real reason the cherished symbols had to go was purely technical. Claims of ideological bias on the part of the authorities were unfair, he said; the issue was exclusively one of practicality. The delicate topiary gardens required highly proficient labourers, and none were to be found anymore. One would be forgiven for thinking, if Fernandes were to be believed, that the whole affair had been concocted by nasty rightists with the sole purpose of fueling public outcry. And yet, of course, nothing could be further from the truth.

The Praça do Império, or Empire Square, had always been a thorn in the Left’s side. One of Lisbon’s grandest public areas, it is also among Europe’s largest. The square is, indeed, imperial: connecting the river to the magnificent Monastery of the Hieronymites, it celebrates five centuries of Portuguese discoveries, colonisation, and expansion. The Praça shines with unapologetic patriotic symbolism. It was from there, once the ‘praia do Restelo,’ that Vasco da Gama initiated his history-changing journey to India. The Jerónimos serve as the pantheon of many of Portugal’s most celebrated men: Gama’s tomb is located there, as is that of the country’s national poet, Luís de Camões. King Manuel I, who oversaw the zenith of Portuguese power in the 16th century, is buried within its sturdy, silver walls. The nearby Torre de Belém, too, is a much beloved symbol of Lisbon.

The square itself is a more recent creation—its complex history further helps elucidate the Woke Left’s rabid hostility. Its origins go back to the 1940 ‘Exposição do Mundo Português’ (‘Exhibition of the Portuguese World’), when the national-conservative government of António de Oliveira Salazar celebrated 800 years of the nation’s independence in uncharacteristically immodest style. Much like Mussolini’s Esposizione Universale Roma, or Stalin’s VDNKh in Moscow, the event was an extravagant display of national vitality. The flower of Portugal’s artistic milieu was invited to participate in the conception of the numerous pavilions, museums, sculptures, and gardens. The organisers had a full-size galleon, Nau Portugal, built and placed on the nearby river, overlooking the event. A work designed by one of the country’s most famous modernist architects, Cottinelli Telmo, and brought to life by the great sculptor Leopoldo de Almeida—the Padrão dos Descobrimentos (‘Monument to the Discoveries’)—was erected. Behind it, at the heart of it all, stood Empire Square.

The Praça was one of the few survivors of the 1940 Exhibition. Most of the complex had been built in perishable materials. Popular acclaim, however, encouraged permanence. Twenty years later, after the original structure had succumbed to age, Salazar decided to rebuild the Padrão in stone for the 1960 celebrations of Prince Henry the Navigator’s birth. It was then that the imperial coats of arms—representing the then Portuguese overseas provinces of Angola, Mozambique, Cabo Verde, São Tomé e Príncipe, India, and Timor—finally made their way into the square. Along with them, the topiary garden featured the symbols of Portugal’s mediaeval orders of chivalry and provincial capitals. Like the Padrão, they were soon the object of civic pride. Beloved by Lisboners, they were kept long after the commemorations. What had appeared as ephemeral became inseparable from the genius loci—the soul of the place.

Our first petition drew thousands of signatures. It was not enough to prevent the coming iconoclasm. Faced with unexpected opposition, Sá Fernandes simply changed his strategy. He pretended to drop the matter—and wait for a better moment to strike.

The second round would not come before Christmas 2020. With the public distracted by the seasonal festivities, the City Council discretely announced that work on the Praça do Império would commence in earnest: the Square was to be redesigned, and the problematic gardens removed. The concerns we had expressed years before were to be ignored. With a bit a luck, they thought, we wouldn’t even notice what was going on. By the time we did, Lisboners would be presented with a fait accompli.

This was an intelligent, if cynical, ploy. But it was destined to fail because we did notice what was going on, and we lost no time in preparing counter-measures. Rather than giving up, we doubled down: a new petition was promptly readied. As in 2016, Nova Portugalidade rallied some of the country’s most respected voices in the denunciation of this wanton demonstration of Woke barbarity. In typical fashion, the far Left attempted to portray us as extremists, and to portray opposition to the proposed act of state-sanctioned vandalism as a vendetta by ‘neo-Salazarist’ misfits. The attempt failed. As they came to discover, there is surprisingly little that totalitarian hate can accomplish when faced by the power of reason, patience, and civility. It was not long before it became clear who was the sect—and who spoke for the quiet majority.

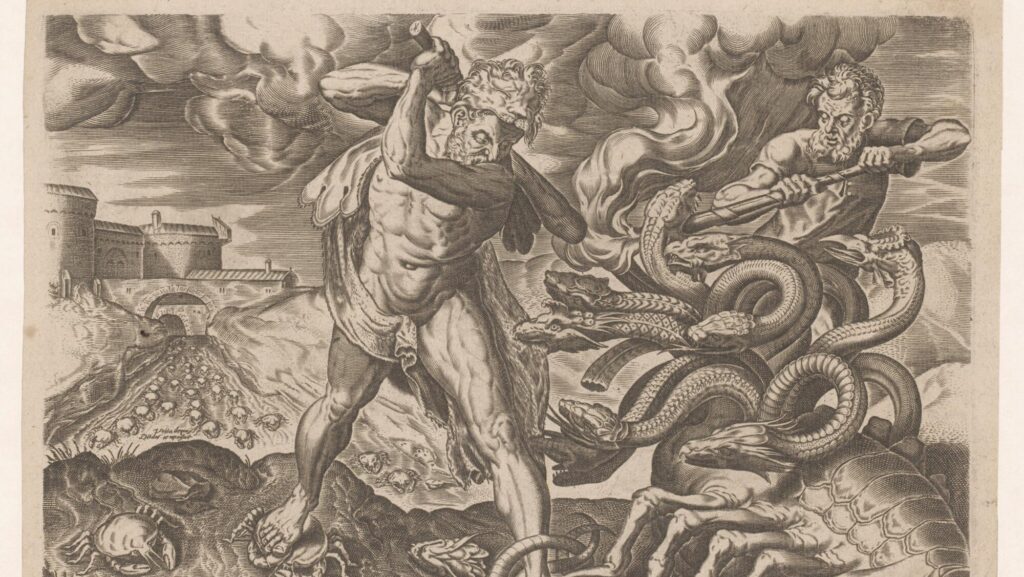

When the office of the mayor called, asking for negotiations on the future of the area, we knew the fight was ours. The Square was to be defended by a delegation comprised of Miguel Castelo-Branco, a historian, Pedro Formozinho Sanchez, an architect with decades of experience in municipal matters, and myself. Talks between us and the Socialist mayor of Lisbon would be long. But they were, also, surprisingly amicable. Both sides understood there was no way around dialogue. By then, Nova Portugalidade spoke with the weight of the 15,000 citizens who had signed its petition—we were too strong to be ignored. The City Council, meanwhile, was the sole institution that could give us—and the people of Lisbon—what we wanted. And, although the art of compromise always requires concessions from both parties, we managed to prove, to Portugal and the world, that the Woke hydra can indeed be beaten.

The new Praça do Império was inaugurated almost exactly a year ago. The coats of arms of Portugal’s former overseas provinces, Lisbon’s daughters by language and civilisation, remain proudly in their place. Keeping them in their original format was impossible: despite our best efforts, the resources to recreate a municipal gardening school, an essential effort if the necessary staff was to be guaranteed, simply did not exist.

Instead, the heraldic elements were reborn in the form of Calçada, a type of public pavement unique to Portugal. They stand today as a magnificent tribute not only to a past of glory, and a future of friendship among the peoples of the Portuguese world, but also to tradition and craftsmanship. Fate would have it that the task of sculpting the new arms fell to Agnelo Alves, a skilled Caboverdian calceteiro (paver). He seemed wholly unimpressed by the controversy surrounding the symbols. Among the imperial-era crests he produced was that of his own homeland—it was his favourite commission.