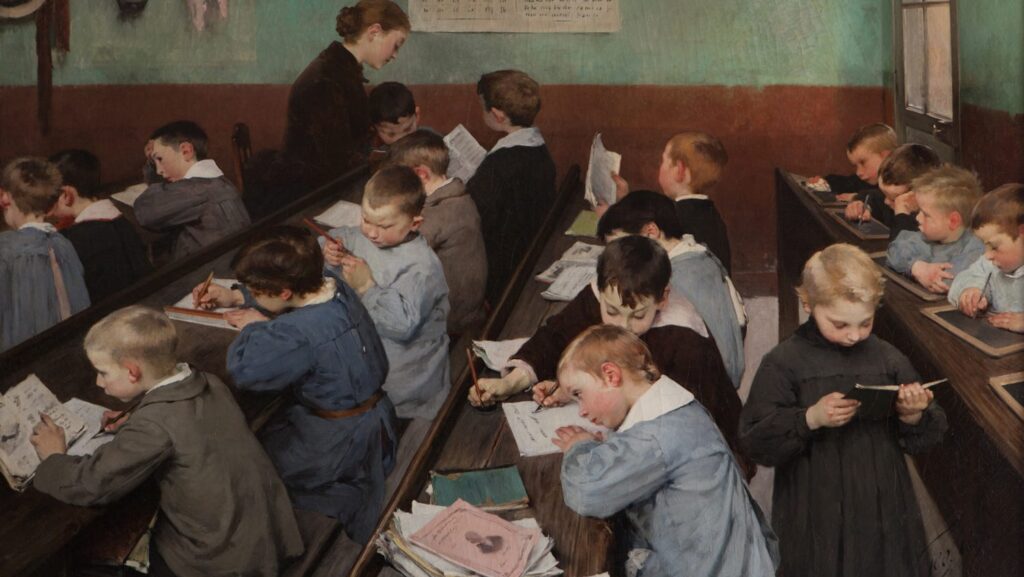

En classe, le travail des petits (1889), oil on canvas by Henri Jules Jean Geoffroy (1853-1924)

The work of Dalmacio Negro Pavón reveals that politics cannot be understood without anthropology: the various conceptions of humanity throughout history are not mere theories but paradigms that have shaped the lives of peoples and conditioned political thought.

“The very spring and root of honesty and virtue lie in good education.” So said Pseudo-Plutarch in the 1st century. This guiding principle was vital in the establishment of formal education in the UK. In fact, this notion has driven our shared conception of education and its purpose from St. Augustine’s first grammar school in Canterbury, to King Alfred’s belief that the acquisition of wisdom which resulted from intellectual formation was essential to his kingdom, to the grammar school revolution of the 16th and 17th centuries, and onwards to the mid-19th century schools and education policy. Yet we see very little of this understanding of education now. With some notable exceptions—the Jubilee Centre in Birmingham, for example—the British educational establishment has lost its once strongly held belief that the purpose of education is to inculcate virtue, replacing this with a different priority.

In 2014, the Department for Education released guidance on promoting what they referred to as “British Values” in schools. These values, outlined in the UK Conservative government’s PREVENT strategy of 2011, were identified as the fundamental pillars of British society that must shape our identity. These ‘values’ were understood to be the rule of law, individual liberty, democracy, mutual respect, and tolerance of different faiths and beliefs. Interestingly, this wasn’t the first time ‘values’ had been emphasised by a Conservative government. Mrs. Thatcher, during her 1983 election campaign, famously spoke of “Victorian values.” Later, in a radio interview with journalist Peter Allen, she elucidated the essence of these values:

Peter Allen: “I would like to begin as well by asking what you meant recently when you talked about Victorian values. What values are they? What do you mean?

Margaret Thatcher: “Well, there is no great mystery about those. I was brought up by a Victorian grandmother. You were taught to work jolly hard, you were taught to improve yourself, you were taught self-reliance, you were taught to live within your income, you were taught that cleanliness was next to godliness. You were taught self-respect, you were taught always to give a hand to your neighbour, you were taught tremendous pride in your country, you were taught to be a good member of your community. All of these things are Victorian values. They are also perennial values as well.”

Mrs. Thatcher’s interpretation of Victorian values seems to me to have been somewhat linguistically anachronistic. What she referred to as ‘values’ would have been considered virtues by her grandmother. This linguistic discrepancy reflects a cultural shift that has occurred, in which the understanding of virtue has waned and given way to a focus on values. This change may be traced back to the ideas of Friedrich Nietzsche in the 1880s. Nietzsche challenged the traditional concept of virtues, advocating for their critical examination and re-evaluation. He called for a complete “transvaluation of values,” and sought a radical reorientation of moral perspectives rather than the mere substitution of one set of virtues for another. His concept of transvaluation marked a departure from the long-established understanding of virtue and paved the way for the more subjective and relativistic ‘values-based’ conception of human development. Nietzsche’s emphasis on personal values as subjective constructs of meaning rather than the universal and habitually acquired virtues has since become pervasive across many domains, not least in education.

The shift from virtues to values carries significant implications due to their contrasting nature. Values, being largely subjective in apprehension and interpretation, and influenced by societal trends and market forces, are prone to fluctuation over time. Consumerism and materialism have led to the prioritisation of perceived values such as wealth and success, while the influence of social media has shaped values centred around appearance and popularity. On the other hand, virtues are rooted in the timeless principles of human nature itself, these principles transcend societal changes and personal preferences. Virtues like honesty, courage, and compassion orientate our moral compasses in a way that remains constant across different contexts and cultures, even if lived and applied differently in those particular contexts and cultures.

Many of us are prone to use the word ‘values’ with no ill intent—I use it all the time! But when we apply it to developing the character of our children caution is required. Now, so called “British Values” are ubiquitous in our schools: every school is required to teach them, every teacher is required to model them, and every student must respect them. We are all familiar with the prevalence of tolerance as a value—yet without virtue to temper this value, it has turned into a totalitolerance. We now find ourselves in the position that Lewis describes in The Abolition of Man:

In a sort of ghastly simplicity we remove the organ and demand the function. We make men without chests and expect of them virtue and enterprise. We laugh at honour and are shocked to find traitors in our midst.

The impact of this shift in education from virtue to values has been grave indeed, shaping the way students perceive and navigate the moral landscape. Without a solid grounding in virtues, students in the UK now regularly encounter difficulties in grappling with moral and practical complexities, as the focus on values has led to a relativistic and superficial understanding of human flourishing. The effect accumulates over the duration of a person’s lifetime. We see the impact of this superficial understanding all around us. An idea now pervades society that one can demand someone else “does the work” or “educates himself” rather than the old idea of—as the Christian tradition would put it—death to self. The lack of a shared understanding of virtues now hinders the development of character and diminishes a sense of responsibility among our school children, and, indeed, university students.

Paradoxically, then, despite the subjectivist nature of values, their prioritisation has led to an increasing tendency to demand that others conform to ever fluctuating beliefs and principles. This is because, not being rooted in our nature in the same way as virtues, the veracity of values is largely judged according to the number of people who accept them. Thus, we witness mounting pressure to be in step with current opinion, requiring alignment with whatever the prevailing, time-oriented set of values happen to be. The demand from the gatekeepers of these values is that others must “do the work” to come in line. In contrast, orienting oneself around virtues plays a large role in pursuing Saint Paul’s exhortation to the church in Rome, “do not be conformed by this world but be transformed by the renewal of your mind.” Emphasis on virtue reminds us that true moral development requires personal commitment and effort first to change oneself. Yet it also allows us to appeal to a set of a-temporal truths which, unlike values, are not dictated by the market or the fashions of the day. It is by becoming virtuous that we may then challenge those around us and those, perhaps, in our schools.

In his book entitled The Book of Virtues, the American conservative politician and political commentator William J. Bennett says:

Today we speak about values and how it is important to ‘have them’ as if they were beads on a string or marbles in a pouch. But [the stories in this book] speak to morality and virtues not as something to be possessed, but as the central part of human nature, not as something to have but as something to be, the most important thing to be. To dwell in [the chapters of this book] is to put oneself, through the imagination, into a different place and time, a time when there was little doubt that children are essentially moral and spiritual beings and that the central task of education is virtue.

This sums up the misstep I believe we have taken and what we need to reclaim. Let’s teach children how they should be and the virtues they should seek to grow in themselves. There is no other way to a happier world.