One wet and chilly morning in June 1815, two great armies faced each other across a valley. Two legendary commanders prepared to meet each other in battle, as the fate of Europe hung in the balance. The old ways collided with the new in the final chapter of a war that had lasted a generation. The forces of the Seventh Coalition made their stand against the French Army of the North, a few miles away from the small Belgian village called Waterloo.

The Battle of Waterloo is one of the most famous engagements in the history of warfare, and rightly so. Its importance, both political and cultural, is hard to underestimate: the epic finale of a struggle against Napoleon, it effectively ended a centuries-old feud between Britain and France, secured the new European borders, and was followed by almost 40 years of peace. It was also a victory of conservative powers over the heir to the French Revolution.

Hopes were high after Napoleon first abdicated in 1814. Monarchs and representatives gathered in Vienna to discuss the future of Europe, but negotiations were interrupted by the news of his return. Despite their newly emerged differences, the states joined forces again, declared war on the wayward Emperor, and began raising troops. Great Britain and Prussia were the closest; others promised to send reinforcements. Meanwhile, Napoleon planned to advance into the Netherlands, expecting to defeat the Coalition members one by one. His Army of the North was 125,000 strong, with mighty artillery, numerous cavalry, and the Imperial Guard.

The Allies gathered everyone they could find at such short notice. Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher, a lively and passionate 72-year-old field marshal renowned for his role in the Battle of the Nations (October 1813), led 120,000 men across the Prussian border. Unlike Prussia, Great Britain did not boast a large army, as most of her veteran battalions had either disbanded or been sent to fight in North America. However, she had a champion worthy of the challenge before him: Arthur Wellesley, the Duke of Wellington, whose impressive battle record earned him recognition both at home and abroad. Often described as “cold and calculating,” he was a master of defensive warfare, with extensive knowledge of his enemy and experience of commanding a multinational army. The latter proved helpful since only a fraction of his 93,000 men were trusted troops from the Peninsular War; the rest were freshly trained British recruits, Dutch soldiers, some of whom had formerly served under Napoleon, and Germans from Hannover, Nassau, and Brunswick.

The campaign began well for the French. Napoleon separated the allied armies, sent Marshal Ney to capture the operationally important crossroads of Quatre Bras, and concentrated on Blücher. On 16 June 1815, the Prussians were defeated at Ligny but managed to retreat in good order. Despite being wounded, the plucky old field marshal remained in command and refused to withdraw to Prussia, saying that he had given his promise to Wellington and was not about to break it. Thus, he marched north, pursued by Marshal Grouchy and around 30,000 French soldiers.

In the meantime, Ney failed to secure Quatre Bras. The Allies suffered losses but held firm while reinforcements continued to arrive. Later in the evening though, Wellington received disturbing news: the Prussians had been beaten and were retreating in an unknown direction—perhaps withdrawing east, never to return. He had no more use for the crossroads and decided to find a suitable defensive location. One in particular caught his attention: a valley with a ridge and reverse slope that could protect his men from artillery fire and conceal their movements from sight.

On 17 June, it was raining. Every bit of ground was soaked with water and turned into mud. About 67,000 allied soldiers made their way into the valley, feeling rather miserable. This mud, however, would happen to be one of their most significant advantages, slowing down the French and saving many lives from cannonballs. Still, Wellington was under no illusions regarding the ordeal they were about to face—unlike Napoleon, who, on the contrary, was overconfident. On the morning of the battle, 18 June, he declared to his staff “that Wellington is a bad general, that the English are bad soldiers, and that this affair will be over before lunch.”

Somewhere between 10:00 and 11:30, Napoleon made his first move, attacking Château d’Hougoumont, a medieval compound turned into a fortified outpost on Wellington’s right flank. However, the target turned out more resilient than expected. Guarded by a fierce Scotsman and his Coldstream Guards, it repulsed every French assault coming its way and endured a bombardment that destroyed almost every building by the day’s end.

Soon after the first Hougoumont skirmish began, Napoleon’s Grand Battery opened fire at the Allies’ centre. As the Emperor watched the cannonade, he spotted what looked like a shadow of the cloud on a faraway meadow. But he knew better. Those were soldiers marching towards the battlefield. Was that Grouchy, returning after scattering the Prussians? Napoleon certainly hoped so. Regardless, he had more urgent matters to attend to: after all, it was already lunchtime, and the troublesome sepoy general still stood between him and Brussels.

Wellington was busy too, riding along his thin line—a formation that required an iron discipline but was deadly against attacking columns. At a moment, he stopped on a hill under a large elm tree and assessed the situation; from there, he saw a bulk of French infantry crossing the valley.

The farm of La Haye Sainte, defended by the King’s German Legion, was the first to exchange fire with the advancing enemy. The next wave smashed into the Dutch battalion, tore it apart, and engaged the British line. It too crumbled under the pressure. The centre nearly fell but was saved by the timely arrival of heavy cavalry. Dragoons charged down the slope, cutting through the French and capturing their eagle. Fine horsemen on first-rate mounts, they were inexperienced and led by Wellington’s overly ambitious second-in-command. Despite all attempts of recall, they rode on, reached the Grand Battery—and were counter-attacked by fresh cuirassier and lancer regiments. Valiant, but ultimately futile, this charge resulted in heavy losses. Surviving riders found cover behind the ridge, protected by the restored line.

It was now France’s turn to show off her cavalry. As the cannonade continued, Wellington noticed that one of his detachments was too exposed and ordered it to pull back. Marshal Ney mistook this movement for general retreat—wishful thinking on his part—and sent cuirassiers to finish the job. “[W]e saw large masses of cavalry advance: not a man present who survived could have forgotten in after life the awful grandeur of that charge,” wrote later an English officer: “You discovered at a distance what appeared to be an overwhelming, long moving line, which, ever advancing, glittered like a stormy wave of the sea when it catches the sunlight. On they came until they got near enough, whilst the very earth seemed to vibrate beneath the thundering tramp of the mounted host. One might suppose that nothing could have resisted the shock of this terrible moving mass.” But the British were prepared. Infantry battalions formed squares, virtually impenetrable for cavalry, and stood fast, like boulders against the waves. Aware of the power of inspiration, Wellington stayed with his men, despite the danger and losses suffered by his staff. Marshal Ney also led the charge personally, having no less than five horses killed under him. Attacks continued for two hours until he finally admitted his mistake and changed tactics.

The second assault of the French infantry was far better executed. Artillery pounded the defenders’ ranks while columns crossed the valley yet again and pushed with all their might. La Haye Sainte fell and Wellington used his last reserves to close the gap in the centre. “Every Englishman on the field must die on the spot we now occupy,” he replied to a plea for more reinforcements. By this time, some Dutch and Hanoverian troops had had enough and deserted, spreading panic as they ran. But others closed ranks and carried on, just as their commander requested of them. Then they heard cannons roar on their left. The soldiers earlier seen by Napoleon had joined the battle, only they were not Grouchy’s men. They were the Prussians.

True to his word, Blücher came to his ally’s aid and broke into Napoleon’s right flank. The first Prussian corps to arrive emerged from the nearby forest and stormed the village of Plancenoit, a crucial tactical point in the French rear. The next concentrated on Papelotte, directly supporting Wellington’s left. This new threat siphoned off a considerable number of French troops and gave the Allies a much-needed respite.

Napoleon’s plans were distorted by action in Plancenoit and Papelotte. But he could still win this. Should the British break, enough forces could be committed to fend off Blücher and possibly finish him too. And so Napoleon sent forth his most formidable units that had never known defeat: the Middle and Old Imperial Guard. Two battalions recaptured Plancenoit while the rest marched onto the weakened enemy line, past countless bodies lying on the ground after a day of relentless fighting. “[W]e saw the bearskin caps rising higher and higher as they ascended the ridge of ground which separated us, and advanced nearer and nearer to our lines,” an officer recalled. One by one, British brigades were thrown back until nothing but swaying grass and an empty road remained before the Guard. The way to Brussels was clear. Triumphantly, they marched ahead—right into Wellington’s trap.

“Guards, get up and charge!” he ordered, and suddenly the grass came to life, as British Foot Guards arose and unleashed devastating fire upon the French. Then they fixed bayonets and charged while the Guard fell to the flanking skirmishers. And then the impossible happened: the Imperial Guard broke and ran. News of their defeat spread like wildfire. “The Guard is retreating! Every man for himself!” was heard across the French formations. Wellington ordered a general advance.

Napoleon watched his army disintegrating and knew that his cause was lost. He escaped the battlefield but surrendered to the British a month later and spent the rest of his days on the island of St. Helena. A new peace was signed in Paris; this time, it would last.

“[The Battle of Waterloo] is a work of art with tension and drama, with its unceasing change from hope to fear and back again,” wrote Stefan Zweig in his 1927 book Decisive Moments in History. He could not have been more right. Waterloo is an important historical event, but it is also much larger than that. It is a symbol, a legend woven from individual stories of its heroes—the British, the German, and the French. All of them displayed gallantry worthy of remembrance.

Waterloo leaves an imprint on our minds, tragic for some and uplifting for others. It tells of pride and courage, of honour and ambition, of loyalty and fortitude. It is a legacy of the European nations; one we can search for the resolve necessary to fight our modern battles. So let us look back on that one morning in June—and let us find hope.

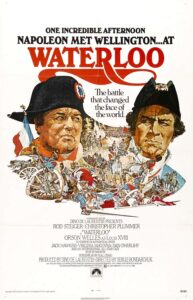

[Editor’s note: The European Conservative doesn’t normally give film recommendations, but in this case the Editor has to mention Sergei Bondarchuk/Dino de Laurentiis’ 1970 film Waterloo. With Rod Steiger as Napoleon, Christopher Plummer as Wellington, and a supporting cast that includes Virginia McKenna, Jack Hawkins, Orson Welles, and Sergo Zakariadze, it is certainly worth seeing.]