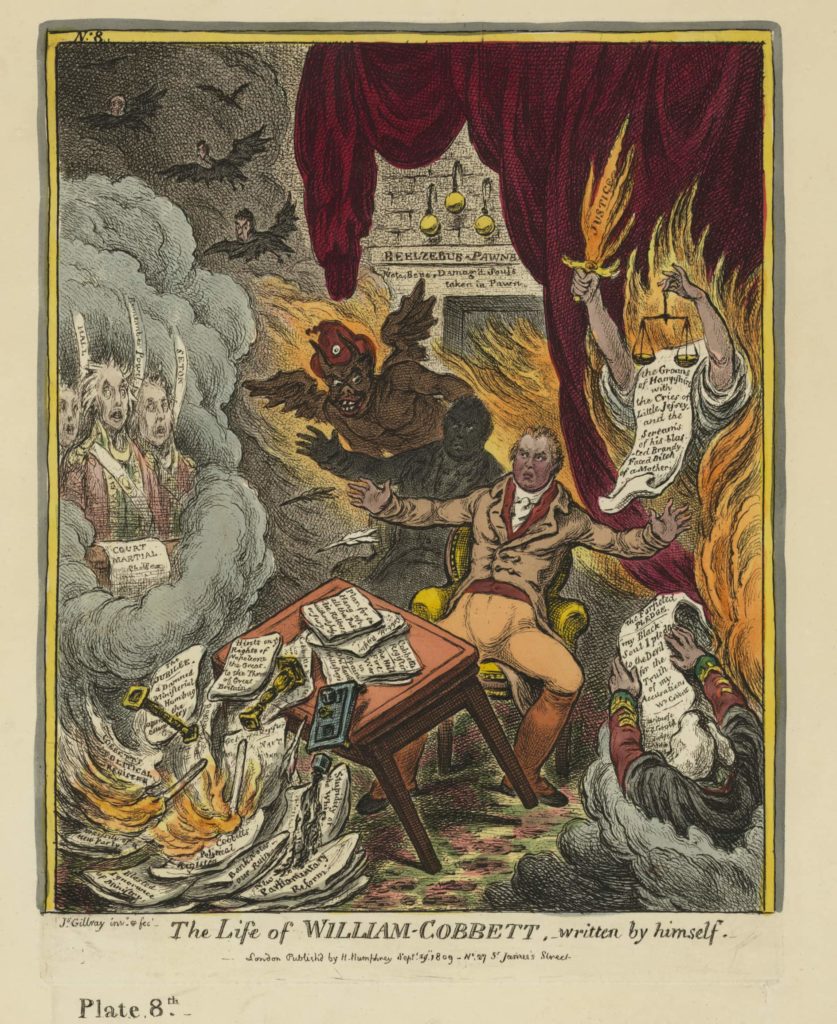

William Cobbett, depicted in this engraving by Mary Dorothy George, surrounded by flames and ghosts, falls backwards, knocking over his desk. From the Catalogue of Political and Personal Satires currently preserved in the Department of Prints and Drawings at the British Museum; also located in the collection of British Cartoon Prints Collection at the U.S. Library of Congress.

PHOTO: PICRYL.

William Cobbett (1763-1835) was not an intellectual. Those looking among the early counter-revolutionary thinkers for robust and scholarly arguments, tightly constructed and leading to punchy conclusions, will be disappointed by the rambling writings of Cobbett. Indeed, that is exactly what Cobbett was in every sense: a rambler. The expansive thought of men like Burke, Maistre, Bonald, and Cortés, for all their shortcomings, succeed in incorporating theological, philosophical, political, historical, and cultural insights into a coherent worldview which each one develops over a vast body of works. Cobbett, on the other hand, is interested in this, and then he is interested in that. He picks up a topic, deals with it, and moves on to the next, expecting his reader to see the sense in how he has engaged with it, but not expecting the reader to adopt his worldview—he is not really aware of having a worldview at all. Indeed, he rather expects the average reader to be, on the whole, too stupid or too malicious to adopt his perspective on anything. He has good reason for distrusting his readership, namely that a reader should not be trusted simply on the grounds that he can read. Here we reach the heart of what Cobbett is all about: the ‘little guy’—that is, the chap who cannot read, who is at the mercy of others, who is vulnerable.

Cobbett’s entire life and writings centre on sticking up for the little guy. This is the major theme of his existence. It has been said time and again that Cobbett changed his mind because he started off as the highest of High Tories and ended up the most radical of Radicals. In fact, one thing Cobbett never did was change his mind. Cobbett had a mind that couldn’t really change, because it was filled not with abstract ideas but with concrete ideas, ideas derived immediately from his experiences and those experiences were unchangeable. He became a Radical because it was as a Radical that he believed he could be truest to Tory principles. During his lifetime, it was not Cobbett who changed but the Tories.

Cobbett was not born into the ascending industrial Whig oligarchy and nor was he born into the old aristocracy. He was the son of a yeoman farmer, and he spent his childhood shooting crows off tree branches. He was born into that class of the English whose faces are pulled out of the earth like turnips and who want nothing more than to remain a part of that soil from which they have drawn all their vitality. Chateaubriand describes this class in his Mémoires d’Outre-Tombe: “They hunted the fox or shot pheasants in the autumn, ate fat geese at Christmas, shouted ‘Hurrah!’ for roast beef, grumbled about the present, praised the past, cursed Pitt and the war, which sent up the price of port, and went to bed drunk only to begin the same life all over again the next day.” Basically, Cobbett was born into a wholesome class who liked doing homely things, and he objected to the destruction of what was wholesome and the scarcity of such necessities as a home.

This massive bulldog of a man was a Tory through and through. He was a Tory because he identified Toryism with the pre-industrial, agrarian, subsidiary, localist, organic, homely, pious, traditional, Merrie Olde Englande that was an affront to everything Whiggish. He called himself a Tory when he believed that Toryism was about protecting the common inheritance of all the English. When Toryism became indistinguishable from Whiggery under the oligarchies of Pitt the Younger, Castlereagh, and Peel, Cobbett called himself a Radical. He joined the Radicals to further the cause of Toryism. His mind did not change.

Cobbett campaigned against Peel’s proposals to found a police force. Peel insisted that his police would be different to the thugs who went by the same name employed by continental despots, and Peel put his policemen in top hats to prove it. Cobbett believed that the top hats wouldn’t suffice and held that within a short time Peel’s police would be indistinguishable from the brutes over the Channel. Anyone who knows anything about UK police will know how prophetic the insights of Cobbett were. He would have preferred that everyone know better how to use their fists than they be forbidden to use them and rely on the concealed weapon of an absent policeman. Today, fists remain forbidden, and the officer remains absent, but his weapon is no longer concealed. Cobbett would have asked, “Is this the community policing we were promised?” And there lies the ever-present concern for Cobbett: the community, the little guys—the guys that always seem to get trampled.

This concern for the little guy is what inspired him to write his History of the Protestant Reformation while he was championing the cause for Catholic Emancipation. He asked himself simple questions: if the Reformation in England marked the liberation of the people from superstition and the tyranny of priestcraft, why was it that sparsely populated villages across England had enormous gothic churches? Could it be that really this had been the people’s religion, which they had treasured, and which they had been bullied into abandoning, and then uprooted and forced into the towns to fill the wallets of a new oligarchy who were the sole profiteers of the Reformation? If the Reformation had indeed marked a liberation of the people, as the English myth claims, why were the great abbeys and monasteries, which had served the poorest of the poor for centuries, razed to the ground? Why, indeed, were there families throughout the country who had been ennobled in the 16th century and now lived in large houses called ‘Abbeys’? If the Reformation had brought in a liberation of the people, why had it required armed militias? Could it be that the rich had taken full advantage of the King’s predicament to become richer, and the little guy had suffered yet again? Cobbett concluded that the story that the English had been told about the Reformation was a big fat lie, and he proceeded to say so in a book, the outrage surrounding whose publication delighted him no end.

His concern for the little guy launched him into what today we call ‘investigative journalism.’ He travelled the south and midlands on a horse, talking to the rural poor. He found that there was a massive population who had lived on the land and provided the country with food and clothing for centuries, and who were now being forgotten in the rapacious industrialisation of the country. Such people had been presented with a choice by the age in which they happened to be born: remain in the countryside and die in grinding poverty or move to the towns and die in grinding poverty. In the country they would have only themselves to blame for their wretched condition, and in the towns, they would have to be grateful to their employers for their wretched condition. He took his findings on the rural poor, and the extraordinary wealth of the landowners who were never seen, to the powerholders in the ‘Wen’—his name for London—and published them as Rural Rides with great success. Again, Cobbett had one objective: sticking up for the little guy.

Even his pocket-sized manual, Cottage Economy, was written with one thought in mind: alleviate the hardships of the poor. He wanted the poor to know how to be thrifty, so that they could live well. He begins the text with the basic premise:

For a family to be happy, they must be well supplied with food and raiment. It is a sorry effort that people make to persuade others, or to persuade themselves, that they can be happy in a state of want of the necessaries of life. The doctrines which fanaticism preaches, and which teach men to be content with poverty, have a very pernicious tendency, and are calculated to favour tyrants by giving them passive slaves.

Cobbett, however, does not fall into the socialist error of seeking to intensify resentment towards those who have, nor the other socialist error of expecting all material needs to be provided for by the State. Rather, he seeks to ‘empower’ the poor by suggesting how they might develop skills, skills that served him and his own family so well over the years. Brewing beer, baking bread, making mustard, salting mutton, turning pigs into sausages, and so forth. Cobbett’s aim is to make the cottage economical so that the villager’s life isn’t miserable.

Some criticise Cobbett for not giving his voice to the anti-slavery campaign and for vehemently criticising Wilberforce. It ought to be recognised from the outset, however, that Cobbett could fall out with anybody and almost did fall out with everybody. He was a crabby farmer who liked a fight. More importantly, however, it was not that Cobbett was against the emancipation of slaves in the Americas, it was that he was almost entirely indifferent. This may seem inconsistent with the main trait of his character, namely his preoccupation with defending the little guy, the trampled upon, the oppressed. But this preoccupation was always coupled, for Cobbett, with a deep localism—and that is the other key to understanding Cobbett.

Such localism is deemed appalling to the modern utilitarian mind. As Peter Singer has put it, ‘how can moral imperatives depend on something as arbitrary as geographical distance?’ Singer would of course be correct if we all lived in a Platonic realm of pure abstractions—but we do not. In reality, we live in historically relative, culturally conditioned, concrete societies comprising an incalculably complex structure of relationships, pieties, attachments, obligations, and affiliations, all of which are built up through a rich tapestry of innumerable interactions and negotiations, which in turn bestow imperatives and accountability. Cobbett understood this, because Cobbett was a man who almost never entertained abstract speculations in his entire life. Sometimes he appeared to do so, but only because he was trying to put in principle what he knew to be true from experience or prejudice.

Cobbett famously remarked, “I am not a citizen of world…. it is quite enough for me to think about what is best for England.” Cobbett could understand why Englishmen were concerned about the suffering of African slaves in American cottonfields, but he couldn’t understand why Englishmen were simultaneously indifferent to the suffering of English slaves in English cotton mills. For Cobbett, before you start sorting out the problems of the world, you must get your own house in order.

G.K. Chesterton wrote a wonderful biography of Cobbett, whom he admired enormously, but even Chesterton could not write a hagiography of the man as he could for Francis of Assisi. Cobbett was a man who liked to fight, and often found himself wishing he’d asked a few questions before he rolled up his sleeves. He mercilessly attacked Thomas Paine, only to discover later that they had been arguing for much the same policy. He eventually dug up Paine’s bones and brought them back from America to give the revolutionary a splendid burial on English soil in reparation for his vitriol of years before, only then to forget about it all. Paine’s bodily remains were found in box in Cobbett’s study sometime in the mid-19th century, and then lost altogether. Cobbett really loved a fight, and happily went after those who didn’t. As Chesterton notes, he died with many supporters but almost no friends—although surrounded by his deeply devoted wife and children.

For all his faults, we need Cobbett today, or at least something of his fighting spirit, because he really did love the little guy. Our age is dominated by a privileging of the abstract over the concrete, the technical over the experiential, the global over the local, the managerial over the skilled, the virtual over the real, the transnational over the national, the commercial over the domestic, of capital over flourishing. The ‘Wen’ continues to swell as an international metropolis with little loyalty towards the land in which it happens to sit. At the same time, the towns and cities of the midlands and the north continue to be abandoned.

Cobbett would have detested so much about our age and would have been quick to point out that the little guy has been left behind, just as he predicted. In the voracious pursuit of evermore satisfaction and security, we have accumulated a massive deficit in happiness—wherein we might have discovered the true wealth of life. Our age, perhaps more than any other, could learn something from Cobbett—or what today we would call his ‘hierarchy of values.’