Whigs and Tories fighting over reforming the British parliament in 1832. Cartoon by Robert Cruickshank.

Attempting to expound someone else’s thought is always a high-risk endeavor. But since I recently declared Dalmacio Negro Pavón the most significant political thinker in Spain in recent decades, with all due caution, I will outline what I consider to be some of the interpretive keys to Negro Pavón’s thought.

Conservatives used to fear all radical change. But in an era of left-wing cultural supremacy, the prospect of upheaval in the decades ahead has become our only source of hope.

The Left has lost elections in recent memory, but at no point has its grip on our major institutions weakened. Thanks to the Right’s obsession with ’80s-style economics, Woke activists now control just about every important cultural space, from universities and broadcasting to Big Tech and the charity sector. The good news is that this is not the first time the Right has been marginalised. It would also not be unprecedented if conservatives managed to escape such a dire situation. There is a striking analogy between the cultural power wielded by modern Wokesters and the so-called ‘Whig Supremacy’ that ruled Britain for much of the 18th century.

In the 17th century, ‘Whig’ meant a Scottish horse thief and became shorthand for a Presbyterian or similar rebel. In 1679, the word was picked up by the supporters of King Charles II to attack those in Parliament who wanted to exclude James, Duke of York (later King James II), from succeeding to the thrones of the British Isles due to his Catholic faith. ‘Tory’ also began as a slang insult, in this case for a papist outlaw, being derived from an Anglicised corruption of the Irish word for ‘brigand.’ It became equally popular during the Exclusion Crisis. ‘Tory’ was thrown around by Whigs to smear their rivals who thought that James, despite his Catholicism, should remain his elder brother’s heir. As often happens, both slurs came to be worn as badges of honour by either side.

The Whigs lost in 1679, but they got their way a decade later when in 1688 the recently crowned James II was forced, in part by a wave of anti-Catholic bigotry, to flee Britain. Supported by Whig aristocrats, William of Orange—Stadtholder of the United Provinces and Protestant nephew to the Catholic James—lay claim to the throne as William III in a joint monarchy with Mary II, his wife and the eldest daughter of the fleeing King. A Protestant succession was thus secured in an episode since mythologised as ‘The Glorious Revolution.’

It was at this moment, Whigs claimed, that ‘constitutional monarchy’ was born. Later Kings and Queens were allowed some prerogative powers, but they could no longer rule without Parliament, as James had done by proroguing that august body from 1685 onwards. Whigs tended to gloss over the fact that he had done so to extend religious toleration to those not belonging to the established Church, such as Catholics and nonconformists, including Baptists, Presbyterians, and Quakers. When James was ousted, these groups continued to be denied any right to serve in the army or hold public office by a prejudiced, Whig-run Parliament.

So began nearly a century of Whig Supremacy, much more politically and legally powerful than the cultural dominion of Woke activists. Toryism, by this point inseparable in many minds from plots to overturn 1688 and restore ‘arbitrary power,’ was essentially cancelled, being regarded as a danger to the hard-won freedoms of Englishmen. The 1715 Jacobite uprising—when James Edward Stuart, James II’s son, tried to regain the throne by force—offered the pretext for a clampdown. Tories were turfed out of senior government positions. The result was that during the early-18th century, high office was effectively passed around between various Whig families, like the Walpoles and the Pelhams, who controlled Parliament and enjoyed royal favour. Today’s Woke ideologues, while they command the culture, would give up International Pronouns Day for such unchallenged supremacy.

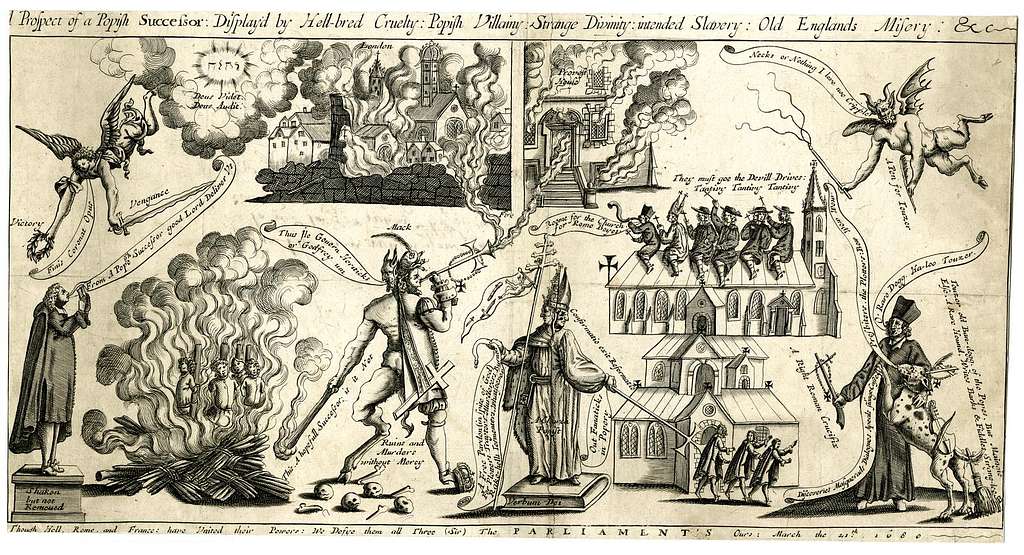

But the Whigs later lost their hold on power. One reason among many was that they grew complacent and devalued political language. It became convenient for Whigs to smear their opponents as a ‘Popish’ menace to the liberties allegedly won by their forebears. Such low-grade tactics are also being attempted by modern progressives. Unsatisfied by past victories, they increasingly like to think of themselves as the last line of defence, if not against ‘Popish tyranny,’ then against an imminent resurgence of empire, racism, and misogyny. Of course, moral equality for all is a nobler cause than barring Catholics from public life, but the notion that such equality is under threat in the modern West is utterly fanciful.

By contrast, for a time there were occasional threats, many quite serious, to the Protestant dynasty and the settlement of 1688. In 1745, another Jacobite army—this time led by the ‘Bonnie Prince’ Charles—advanced as far south as Derby, just 130 miles from London, in a campaign to restore the Catholic Stuarts. But once George III became widely recognised as Britain’s King after James Edward Stuart’s death in 1766, the danger no longer existed. This did not stop Whiggish types from playing on such fears for political gains. Clichéd denunciations of ‘Popish plots’ and ‘arbitrary power’ were still common—rather like the flimsy charges of ‘bigotry’ that continue to be thrown around by radical Leftists today, wildly out of proportion to the number of real bigots.

At home, George III himself became suspected of tyrannical aims because of his desire, as historian Andrew Roberts explains, “to rule through a wider group of ministers than the same families who had run Britain almost uninterruptedly since the Glorious Revolution.” Whig fears of anything more sinister missed the fact that George deeply admired the Revolution of 1688 (after all, it later enabled his Hanoverian Protestant family to become British monarchs) and never asserted his royal powers in contempt of Parliament.

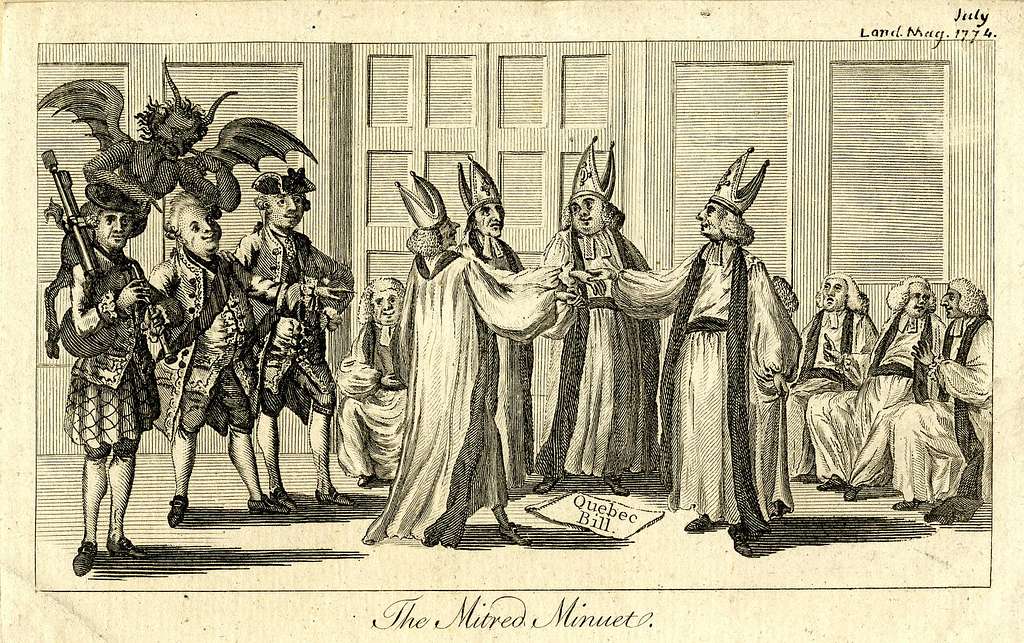

Further abroad, the American revolutionaries of the 1770s, though often mythologised as secular heroes of a ‘liberal Enlightenment,’ began to couch their grievances in a fervently Protestant, Whiggish idiom, absorbed from the mother country against which they now rebelled. Thus we find Daniel Barber, a soldier in the Continental Army, recalling the anti-Catholic fervour with which many colonists enlisted to fight Britain: “We were all ready to swear, that this same George [III], by granting the Quebec Bill, (that is, the privilege to Roman Catholics of worshipping God according to their own consciences,) had thereby become a traitor; had broke his coronation oath; was secretly a Papist… The common word then was, ‘No King, no Popery.’”

This was sheer nonsense. George III was a devout Anglican who refused even to consider William Pitt’s (no relation to the author) 1801 proposal for Catholic Emancipation, precisely because he believed it ‘broke his coronation oath.’ But the narrative was fuelled by a propaganda campaign, well-captured by “The Mitred Minuet”—a cartoon depicting Bishops dancing around the Quebec Act while the Devil whispers into the ear of Lord North, the King’s First Minister. Such symbols, lifted from the Whig playbook, won the day in North America. But they lost their power in Britain as the century wore on and newer threats, notably the French Revolution, became more urgent.

It remains to be seen whether the equally sobering rise of Communist China will force Wokesters to drop their own self-indulgent posturing. (If not, then perhaps recent events in Ukraine may do the trick.) Indeed, the cultural dominance of social justice activists has encouraged an intellectual carelessness similar to that which became common among latter-day Whigs. The economist and social-critic Thomas Sowell has identified a problem of language inflation, writing of race hatred in particular: “Racism is not dead, but it is on life support—kept alive by politicians, race hustlers, and people who get a sense of superiority by denouncing others as ‘racists.’” Everything from Georgia’s election law to the inability of mainstream parties to get Europeans keen on open borders is now blamed on racism, just as other left-wing failures are pinned on whichever ‘phobias’ can be made to fit. Even many liberals now accept that the Woke crowd’s urge to cancel people for ‘hate speech’ is getting more feverish by the day.

However, the resemblance between the Whig Supremacy and the left-wing dominance of modern institutions is not just interesting for its own sake, but potentially instructive for conservatives today. History never repeats itself, but we may have reason to hope it might rhyme in this case, as the Right faces down a ‘Woke Supremacy’ every bit as culturally dominant as the Whig one seemed politically invincible before it crumbled. Moreover, the Whig collapse at the end of the 18th century was followed by a golden age for conservatism—led by Edmund Burke, but also embodied by Pitt the Younger and his successors.

It would never have occurred to either gentleman to identify as a Tory. Even in the late-18th century, to do so would have begged connections with Jacobite plots still within living memory. But while Burke and Pitt would have rejected the Tory label, they were essential—Burke in the realm of ideas, and Pitt by his leadership—to the birth of modern conservatism.

Indeed, at an early age, Pitt recognised how the term ‘Whig’ had utterly lost its meaning. In 1779, just twenty-years-old, he self-deprecatingly referred to himself as ‘an Independent Whig, which in words is hardly a distinction, as everyone alike pretends to it.’ Whiggism, Pitt understood, could no longer mean much in a country where the cause of Jacobite rebellion was dead. The same is happening now with terms like ‘anti-racist’ and ‘anti-fascist,’ worn by the Left as marks of radical distinction, but in fact revealing that they are no different from the rest of us. Pitt at least knew that by nominally calling himself a ‘Whig’ he was doing nothing extraordinary. His ‘Pittite’ successors, who kept the more extreme Whigs at bay and continued to fight the war Pitt had led against regicide France, later grew into the Conservative Party.

While Burke never disowned his Whiggish respect for the ‘constitutional balance’ achieved in 1688, his contributions to conservative thought are unquestionable and immense. ‘Conservatism’ was not used in a political sense until the 1830s, but the basic instincts of conservative philosophy have been sublimely expressed by Burke’s Reflections (1790). Confronted by the lofty abstractions of the French revolutionaries, he called on his countrymen—including more radical Whigs like Charles James Fox, who supported the Revolution and from whom Burke duly split—to reject such idealistic grounds for mass violence. Instead, wrote Burke, they should honour tradition, legal custom, and the social knowledge made possible by an organic order grounded in centuries of human experience.

The Woke denigration of Western culture and history is every bit as deranged, if admittedly not as bloody, as the rampaging fanaticism which seized France in 1789. It cannot be long before people wake up to the fact that, in an uncertain world, there is only so much time to fight senseless battles. This was partly why the Whigs faded. Fox, their esteemed leader, reached for the old canard that Kings, not Robespierre, were the real threat to liberty. Meanwhile, Burke and Pitt paid attention to events on the ground, moving beyond the Whiggish clichés to become the unconscious progenitors of modern conservatism. Fox alienated even his closest allies, many of whom joined Pitt’s government in 1794. Will the Wokesters go the way of the Whigs? As China’s ambitions become harder to ignore and Leftist rhetoric gets increasingly absurd, most people will lose patience with those who regard transgender bathrooms as the moral crusade of our time.

The problem with complacent ruling elites is that, to justify their dominance, they are forced to resuscitate old terrors and to make up new ones. They rely on phantom enemies against which they can pose as our protectors.

But like Fox in the 1790s, radical Leftists will learn that bothering people with dead or imaginary causes soon enough gets tedious. True, the Whigs did leave behind an important legacy. Although it is romantic to imagine Kings and Queens ruling without the boobies in Parliament, no British sovereign has been free to do so since James II. But that is the only lasting achievement of the Whig hour upon the stage. The Wokesters strut and fret for now, but by overplaying their hand they only move closer to the day when they too are heard no more.