America’s economy is on the threshold of a fiscal meltdown the size of which the world has never seen. It is impossible to predict when it will happen, at least with any meaningful probability estimate, but the fiscal dynamite is in place and all we are waiting for is the spark that will ignite the fuse.

When the fiscal meltdown happens, it will send enormous shockwaves through a country where politicians, taxpayers, and voters have gotten used to getting something for nothing with their breakfast eggs. They are in for a rude awakening: an American fiscal crisis—which does not even have to be of Greek proportions relative to the economy—could bring down the world’s largest economy and end America as you have come to know her.

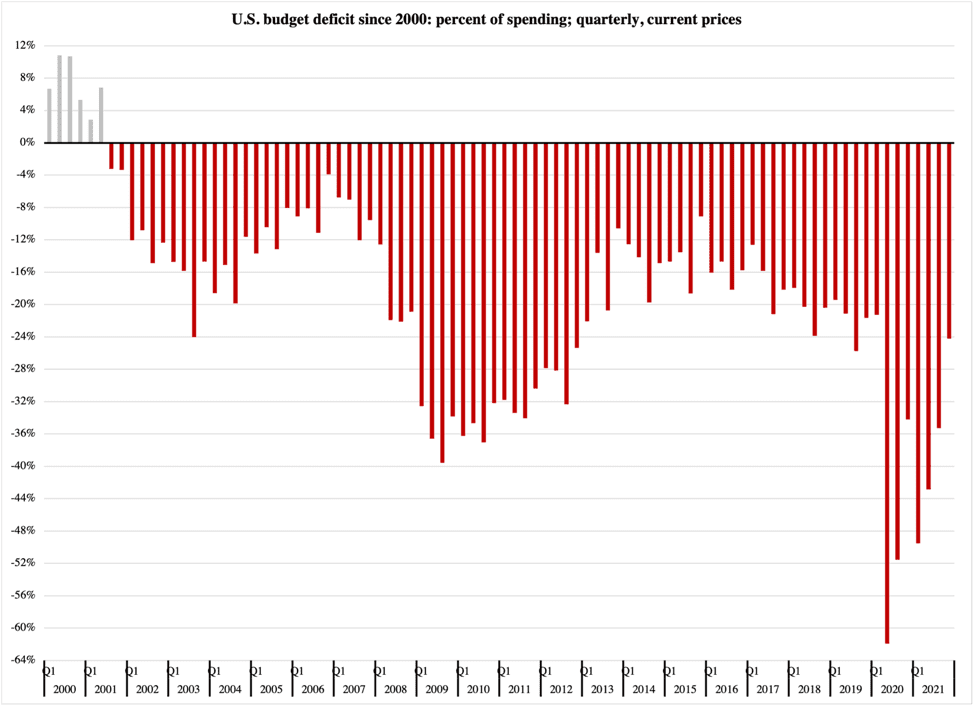

The American federal government has run budget deficits for more than 50 years. Except for four years under President Clinton in the 1990s, the U.S. treasury has been borrowing every year since 1969 to fund part of its current expenditures.

After outrageous levels of borrowing during the recent pandemic, the federal government now owes $30.3 trillion. This equals 126% of current-price GDP—which, keep in mind, has been ballooned by inflation close to 8%.

Although the budget deficit is returning to “normal” levels, this is still $1-1.2 trillion of annual borrowing, just to keep funding the deficit. This is unsustainable; to demonstrate how close the federal government is to a debt meltdown, let us look at just one scenario that could light the fuse. It starts in the war in Ukraine, where the government in Kyiv has moved closer to Russian demands. This includes scrapping the plans to join NATO.

If Ukraine agrees to Russia’s terms, and if Russia leaves Ukraine as a result, Vladimir Putin will get a significant boost in global credentials, not because he will be liked, but because he fought and won a war (no matter how morally unjust) and because he did it while defying Western sanctions.

Here is where the Ukrainian situation connects to a U.S. fiscal crisis. As one measure to circumvent the sanctions, Russia made a trade deal with India that is independent of the U.S. dollar. According to New Delhi Television, NDTV, the sanctions-evading deal would technically rely on Russian banks opening accounts with state-owned Indian banks. The Times of India explains that foreign trade would be cleared without the involvement of the dollar.

A Russian victory in Ukraine would stretch out across the sanctions and give Moscow a reason to expand its India trade model to other countries. It would be a way for Putin to retaliate against America for the sanctions. While Russia secures its foreign economic relations, it cuts demand for the dollar in the bargain.

It would not be relevant for Russia to dethrone the dollar as preferred global currency. All it takes is a big enough movement away from the dollar, to cause a deep dive in the value of the U.S. currency.

When international investors, including central banks, sell off a big chunk of their holdings in a currency, it causes a large excess supply of that currency. This manifests itself in two ways: a decline in its value vs. other currencies—the same 100 euros cost more in dollars—and a rise in interest rates in the currency’s home country. When foreign investors in U.S. stock and treasury securities see the dollar plunge, they sell in order to take home their money as fast as possible.

Since payments on treasury securities are of the fixed coupon kind, a treasury price plunge causes a rise in interest rates.

When interest rates rise for negative reasons, such as in this case, rates will tick up way beyond what is healthy for the economy. The Federal Reserve would normally accommodate this with monetary expansion, but that is not possible in a scenario where there already is excess supply of dollars in the economy. This pushes the responsibility for solving the crisis onto Congress. They, and the U.S. treasury, will have a much harder time borrowing money.

This is where the fiscal crisis begins.

The government of the United States has been running budget deficits for more than half a century; the only time since 1969 that it has run a surplus was in President Clinton’s second term. Figure 1 reports the deficits quarterly, as percent of government spending:

Of the $28.4 trillion that the U.S. government owed at the end of its 2021 fiscal year, 80% is the result of borrowing since the turn of the millennium. One fifth of the current debt is due to borrowing in the past two fiscal years alone.

Since fiscal year 2021 ended on September 30th last year, the debt has grown by an astounding $1.85 trillion. This pace of debt growth will not continue—in the 2021 calendar year the budget deficit fell by roughly $200 billion per quarter—but even under “normal” fiscal circumstances the deficit runs up toward $1 trillion per year. Given changes to federal spending during the recent pandemic, that figure may very well be higher going forward.

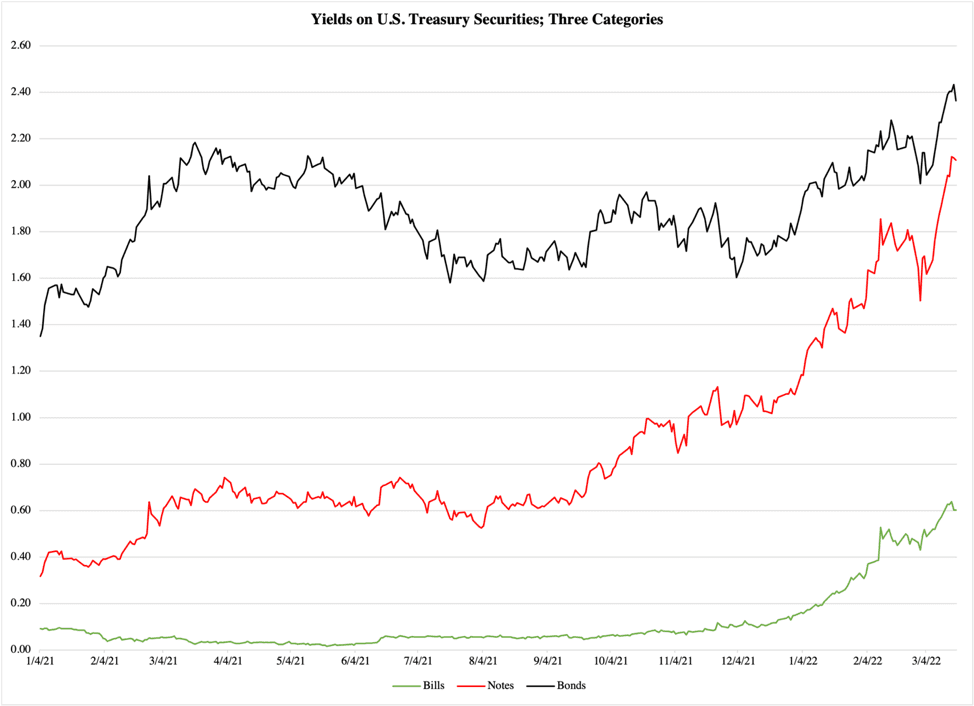

At the end of fiscal year 2021, foreigners owned almost 30% of the debt. Even a moderate sell-off among them would rapidly become a major problem for the U.S. treasury. During the pandemic it shifted its borrowing toward shorter-term securities, which has lowered the interest cost on the debt, from 2.5% in 2019 to 1.7% in 2021. At the same time, it means that the treasury has to borrow quite a bit of money just to renew its already outstanding debt.

When interest rates are rising, for every new round of borrowing, the treasury has to pay more just to keep its current debt afloat. On top of that comes the cost for increasing the debt, due to current budget deficits. This adds up to a rapid rise in the cost to Congress for maintaining the debt. A return to the debt-cost level for 2019 would force Congress to spend $242.2 billion more per year. However, thanks in good part to the Federal Reserve tightening monetary policy recently, interest rates on U.S. treasury securities have increased noticeably in recent weeks:

A run on the dollar, per the “Russian” scenario, would likely more than double these rates, but they would also rise quickly. Therefore, it is not unreasonable to estimate a cost for the U.S. debt at 3.5-4% per year—even if the bulk of the debt is in short-term maturities.

At a 4% average, the treasury would need $1.2 trillion per year just to honor its debt cost obligations. This would make the national debt the costliest regular item in the federal budget, surpassing the social security retirement system by about $40 billion (in estimated 2022 figures). The cost for maintaining the federal debt would be 150% higher compared to 2021. The increase, $726 billion, is almost exactly equal to the 2021 cost for Medicare, the federal health-insurance program for retirees. It is within a hair of the total cost for the American military.

In other words, a fiscal crisis would force U.S. Congress into uncharted territory. Never in modern history has this legislative body been forced to be austere with its resources. When spending has outpaced revenue, they have borrowed money. When the cost and size of government have weighed down the private sector, Congress has cut taxes (under presidents Reagan, Bush Jr., and Trump); the resulting boost in economic growth gives Congress some more time before its inevitable debt default.

That route is now closed. Tax cuts do not work anymore, and you certainly cannot cut taxes when your creditors are running away from your debt. There are only two options:

1. Spending cuts, or

2. Tax hikes.

With a “permanent” budget deficit of approximately $1 trillion and increased debt costs of at least $700 billion, any fiscal measures to close the deficit will only stop the debt from rising. This makes the budget balancing even more urgent: measures to close the deficit will have to go into effect within a year, two tops.

For this reason, deficit reduction will be extremely difficult. Tax hikes equal to $1.7 trillion are unthinkable, especially in one year. They would force Congress to raise personal federal income taxes by almost 50%: for every $1,000 a taxpayer paid in 2021 they would have to pay $1,500 under this scenario. Payroll taxes would go up by 36%.

The only option for Congress is an austerity pact between the Democrats and the Republicans. Among other things, this would allow them to overcome the so-called filibuster threshold in the Senate, according to which most legislation must win support from 60 of the 100 senators. To make this austerity pact work, the two parties would have to agree to a 50/50 split between tax hikes and spending cuts.

Federal income taxes would still have to go up by 25%, a very sharp increase in the burden on the American economy. It would be enough to hurl the economy into a deep recession.

Just like austerity crippled the Greek economy.

Things would get even tougher on the spending side, with $850 billion to be cut in one year. Congress is notorious for protecting its “pet programs” against any measures that do not increase spending fast enough. To ask the elected officials on Capitol Hill to agree to spending cuts is worse than trying to herd cats: it is like sitting down with a bunch of alligators and asking them to go on a diet.

Compared to the spending in the 2022 fiscal year, $850 billion is a 14% reduction. In one year. These are levels that approach what the Greek government did during its austerity years in 2009-2014, but the difference is that the Greeks knew what “cut spending” meant. American lawmakers have no clue. Congress operates under the premise that “spending cut” means that spending is not increased fast enough. Federal appropriations are made according to a “base line increase,” where an increase below the base line is defined as a reduction in spending.

The idea of actual reductions in outlays is so alien to members of Congress that they would rather believe the Earth is flat than actually cut spending. If they did cut spending, some 70% of the reductions would hurt low-to-moderate income families, and retirees. The moral outcry among voters would be unprecedented, especially if taxes went up sharply at the same time.

How likely is it that Congress could maintain an austerity pact? Consider the aftermath of the terrorist attacks on September 11th, 2001. The unity behind the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq lasted one election cycle. In a fiscal crisis like the one considered here, voter dissatisfaction would be far more apparent, enticing opportunistic politicians to defect from the austerity pact and resume promising silver spoons and green lawns to all voters.

It is genuinely impossible to predict where a fiscal crisis would take America. What we can say, though, is that the unthinkable suddenly becomes thinkable, even plausible. The most frightening scenario, which is equiprobable with the best outcome, is that American politics is radically destabilized in either ideological direction. Whichever way the chips would fall, it would open new pathways in politics that are alien to the common American voter.